Fikile Mbalula — PICTURE: SYDNEY SESHIBEDI

Sport and Recreation Minister Fikile Mbalula’s announcement that four of the big sporting federations would be barred from hosting or bidding for “major and mega international tournaments” took sports administrators by surprise.

The minister castigated the affected federations for failing to achieve their transformation targets, and for omitting relevant data in order to disguise their underperformance.

His demands go beyond selection targets to the establishment of transformation committees, and a widening of transformation to encompass sponsorship deals and procurement policies.

Few sports bosses will complain openly about this decision. After all, it represents a legitimate exercise of political power. There is no entitlement to use national symbols where a legitimate government does not believe that the teams involved can meaningfully represent the nation. Critics, however, will quietly lament the plan’s limitations.

First, there is no real strategy to leverage resources to improve sports performance and transformation simultaneously.

Research indicates that there is a strong relationship between national wealth and elite sports performance. Rich countries benefit from good nutrition, physically active children and adolescents, and strong coaching institutions. Many sports require high levels of investment in infrastructure: tennis courts, golf courses, swimming pools and cricket pitches. For international competition, specialist training facilities are vital.

SA cannot compete with wealthier and larger states — especially those that now pursue victory unremittingly. Nevertheless, there are key instruments for changing longer-term sports performance in the hands of Mbalula’s own government. SA has taken almost no action to widen opportunities for participation in public schools, and municipalities have been slow to provide local sports and leisure facilities.

Second, Mbalula has done little or nothing to address poor performance by sporting federations, despite the fact that weak and scandal-ridden institutions cannot effectively drive either transformation or elite success.

According to a study by researchers Manuel Luiz and Riyas Fadal, SA performs badly in sport even when compared with much poorer states. Wealth is a good predictor of footballing success across the rest of Africa, but SA routinely ranks below economic minnows. At the Beijing Olympics, SA was ranked 12th among African countries, with fewer medals than much poorer states, such as Kenya, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe.

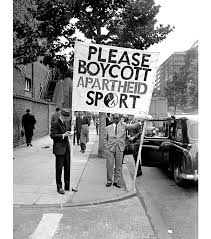

Third, sport can be used to unite people, but it can also polarise society for political purposes. The timing of Mbalula’s decision may flow from an electoral calculation: that the sanctions against sporting federations will remain very popular among black citizens, while generating a racist backlash from sport-loving whites that will benefit the ANC at the polls in August.

Finally, some critics believe the primary beneficiary of the ban will be the person who has benefited most from all of Mbalula’s key initiatives: himself. After joining the anti-Zuma slate at Mangaung, he was lucky to survive in the government. According to Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema, Mbalula was a Gupta-family appointee to the Cabinet: “Unlike (Mcebisi) Jonas”, Malema claimed, “he accepted it and complained later”.

Now Mbalula needs to do something more to secure his future. He has already secured the 2022 Commonwealth Games for Durban. The estimated R10-billion cost of the games will involve a massive transfer from the national fiscus to the ANC’s most powerful province.

But a Cabinet reshuffle is now on the cards. By launching a tremendously popular offensive against the white sporting establishment, he may calculate that he has done just enough, and just in time, to protect himself once again from the axe.

Butler teaches public policy at the University of Cape Town

This article first appeared in Business Day