South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is seen as a model showing how to redress injustice in the aftermath of a bruising conflict. For most of the victims of apartheid it has failed to deliver.

In February 2014, Sri Lanka announced it was considering a process similar to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission to heal the wounds of its decades-long civil war. It sent a team, including two ministers, to South Africa for discussions with the government and the ANC in order to learn how the country had approached the problem of crimes committed during the apartheid era.

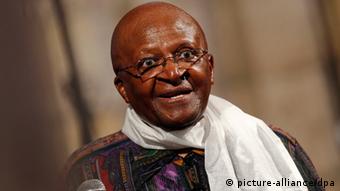

In countries as disparate as Liberia, South Korea and East Timor, officials have also cited glowingly the achievements of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission led by the Nobel Peace Prize winner and former archbishop Desmond Tutu.

However, observers in South Africa itself view this with some suspicion. “I’m rather skeptical, ” said Piers Pigou, South African project director at the International Crisis Group. Contrary to its reputation abroad, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s record could be described at best as uneven. “There is the danger that such commissions could be misused to cynically sweep past injustices under the carpet,” Pigou warned. In his view, that is what the South African government is trying to do.

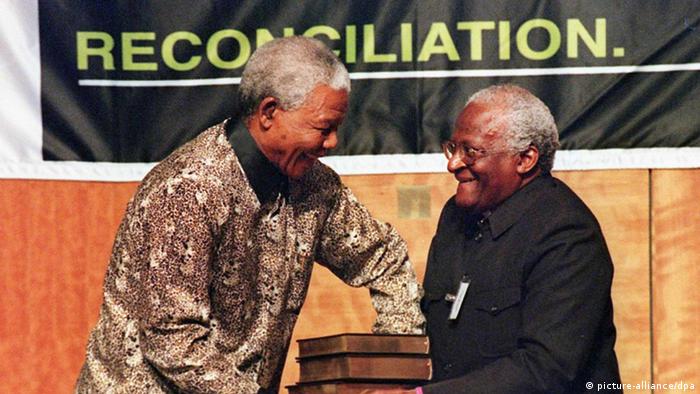

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created by the then President Nelson Mandela, remains to this day the largest enterprise of its kind. From 1996 to 1998, the high profile body heard more than 20,000 witnesses. More than 7,000 culprits applied for amnesty from prosecution which the commission granted in a limited number of cases in return for a full confession.

The statements by the victims – and to some extent the culprits as well – did not only shock the public but also the chair of the commission, Desmond Tutu, who broke down in tears during the first session.

Not enough compensation

Over a period of two years, the commission revealed to the world – and in particular to South Africans – that the crimes committed under the apartheid regime, which included torture, murder and terror attacks, were far worse than many had previously supposed. That also applied to the brutality displayed by fighters of the African National Congress, now South Africa’s ruling party, and other groups.

20 years after the end of apartheid, victims’ representatives and relatives are far from satisfied with the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “It has not accomplished its main tasks,” said Majorie Jobson, director of the Khulumani Support Group (KSG). Specifically, it has failed to give back to the victims their dignity or compensate them.

The commission awarded compensation to 16,000 victims, a figure which Jobson said was far too low. “Even when only counting the worst human rights violations – torture, murder, kidnapping and enforced disappearances – we have identified more than 120,000 victims who deserve compensation,” she said. Most of them never had the opportunity to present their cases to the commission. The KSG represents a group of more than 200 anti-apartheid activists in outlying Limpopo province. When the commission visited the province, only five had enough money to pay the cost of a ticket to get to the hearing.

The KSG and other organizations have been saying for years that the victims’ lists should be re-opened so that more applications for compensation can be lodged, because only a small fraction were able to contact the commission by the allotted date. But even those who submitted their applications in time have received far less in compensation than the sums they were originally promised.

Escaping prosecution without an amnesty

In government circles, such demands for more compensation fall on deaf ears. “Nobody is prepared to say so officially, but the government’s policy is simply to just leave things as they are,” said Pigou. Legal and historical clarification of the crimes of apartheid is also largely being blocked. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission may only have granted amnesty to a small minority of culprits, but the vast of majority of those whose applications were turned down – on both sides – have escaped prosecution. One case is that of Nelson Mandela’s ex-wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. According to the commission, members of the Mandela United Football Club, which she ran, had committed torture, murder and arson.

Public interest in a comprehensive investigation into the past is minimal at the moment, said Pigou. Pressure on the government to act is therefore correspondingly low. Pigou has carried out comparative research into political transition in many countries and has come to the conclusion that you cannot afford to ignore the past in the long term. “Societies that have experienced conflict, or dictatorship, go through a period of memory loss of about 10, 20 or more years. But sooner or later, they feel the need to explore and come to terms with their history,” he said.

In spite of all their deficiencies, truth commissions could help other countries address the problems they have with the past. “But they should learn from what did wrong, as well as from what we did right.” Pigou said.

http://www.dw.com/en/truth-and-reconciliations-checkered-legacy/a-17589671