During the 20th Century alone, we witnessed the death of millions of people as a result of genocide and systematic mass murder.

This includes some 1.5 million Armenians, 3 million Ukrainians, 6 million Jews, 250,000 Gypsies, 6 million Slavs, 25 million Russians, and 25 million Chinese. Then are are 1 million Ibos, 1.5 million Bengalis, 200,000 Guatemalans, and 1.7 million Cambodians. 500,000 Indonesians have died, along with 200,000 East Timorese, 250,000 Burundians, 800,000 Rwandans, and 500,000 Ugandans. More people have died from genocide than in both World Wars.

We often talk about how the horrors of the Holocaust must never be repeated, but history shows this has not been the case. Crucially, we need to identify the ten stages of genocide much earlier – it’s always been clear they don’t happen overnight. In some cases atrocities are the culmination of years, maybe even decades, of hostility, discrimination and political wrongdoing.

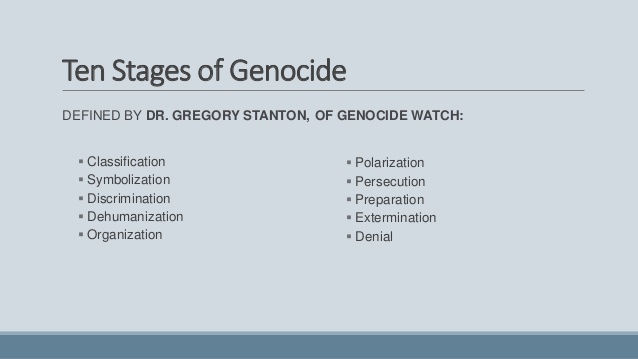

However, spotting the signs of genocide isn’t as hard or as subtle as it might sound. Dr Gregory Stanton, a research professor and the founder of Genocide Watch, coined the ‘Eight Stages of Genocide‘ back in 1998, something since expanded to 10 points. The framework clearly sets out the road to persecution, as well as the remedies available, allowing us to provide effective protection to marginalised groups.

1. Classification

Whether about ethnicity, race, religion or nationality, genocides always start with the idea of an ‘us and them’ – it is what sets the rest in motion. Societies which are the most split and fragmented are seen as the most vulnerable, for example in the ‘textbook genocide‘ underway against Rohingya Muslims. Long-described as “the world’s most persecuted minority,” a history of segregation and lack of citizenship has set the stage for today’s bloodshed.

Stanton identifies the main preventive measure here as simply developing universal institutions that make no reference to difference. This way, barriers between people become almost impossible to raise. Tanzania is a strong example of this, where a shared language has allowed for a far more diverse and peaceful society than what may have been otherwise.

2. Symbolisation

Names, caricatures, colours; we symbolise our classifications. A genocide becomes increasingly likely as we begin to apply these in hate-driven ways to members of groups. The symbols slowly become less about identification, and more about identifying ‘outcasts’. The yellow star for Jews under Nazi Rule, or blue scarves for the Eastern Zone of Khmer Rouge Cambodia, are prime examples of how they’re used to dehumanise real people.

Likewise, the clothing or symbols of a community can be outlawed, thereby denying people the right to identify. Inversely, the use and promotion of symbols such as Nazi Swastikas and KKK costumes can make the wearers feel superior and justified.

Based on this, cultural support for outlawing symbols, such as the Nazi swastika, whilst ensuring that freedom of expression remains in place for non-hate groups, is perhaps the most useful method of fighting against this stage. Likewise, the denial of symbolisation, such as Bulgaria’s refusal to supply yellow badges to the Jewish population, meant that the symbol never generated the connection it did in Nazi Germany.

3. Discrimination

Once classification and negative symbols are in place, discrimination becomes all-too-possible. The targeted group becomes powerless, loses civil rights, and often robbed of even basic citizenship. For example, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 stripped the Jewish population of the right to employment at any government institution or university.

The best preventative measure here comes from full political empowerment and citizenship, irrespective of grouping. By outlawing discrimination in any form, people are able to fight back against violations, as well as being protected against them in the first place.

4. Dehumanisation

The culmination of Stanton’s previous three stages; dehumanisation removes the very base of someone’s identity. We are all revulsed by murder, but this is eliminated if people aren’t seen as people. In the Rwandan Genocide, for example, many partakers failed to comprehend their Tutsi victims were human. Instead, they were seen as ‘cockroaches’ and vermin to be exterminated.

While there must be safeguards in place for free speech, hate speech and propaganda is not part of this. Stanton himself notes that societies who fall victim to genocide rarely have such constitutional protections. He also goes further, recommending those trading in hate speech are banned from international travel, have their finances frozen, their radio stations shut down, and propaganda banned.

5. Organisation

Genocide will always be an organised operation. The state will often take the lead, whilst using militias, rogue officers, or local groups to avoid government responsibility (as seen with the Janjaweed in Darfur). The state will often make it appear informal, whilst funnelling money and aid to the groups willing to execute.

It is important that these militias, and the option of joining them, are made illegal. Stanton also argues in favour of arms embargoes on governments (such as the trade embargoes against Serbia in 1999) and citizens complicit in genocidal massacres, whilst creating commissions to investigate the violations, similar to the National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide in Rwanda.

6. Polarisation

Discrimination, hatred, and extremism drive populations apart. Marriage and even basic social interaction may be outlawed. For example, Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar saw their right to vote rescinded in 2015. Meanwhile, terrorists may target and eliminate perceived moderates to silence the centre-ground.

To prevent this, security must be provided to political figures and human rights groups at-risk from extremists, whilst also guaranteeing greater freedoms of travel if required. Denying extremism the ability to silence other voices ensures that it becomes increasingly difficult for intolerance to spread unopposed.

7. Preparation

States that engage in genocide are fixated by blood. Perpetrators profess through that they have a “final solution” through “ethnic cleansing” or “counter-terrorism” and build task forces and infrastructure that will accelerate their massacres. Once the population is both fearful and loyal, and a victim group has been located, they offer the simple choice of “kill or be killed.”

Arms embargoes, international pressure, and prosecution are just some of the matters that governments can be held to task if they’re thought to be building to a genocide. These all require the support of the international community though – we all need to play our part.

8. Persecution

Once victims have been identified and separated things escalate quickly. Death lists are created, property is removed, and they may be sent to ghettoes, concentration camps, or inhospitable regions of the nation. Massacres begin.

It is at this point that a Genocide Emergency must be declared by the UN, the Security Council could perhaps be mobilised, and armed international intervention. Heavy assistance for the persecuted and humanitarian relief must be introduced as quickly as possible. If it is to reach this stage, as it did in Kosovo, then sanctions simply aren’t enough; more radical action is required.

9. Extermination

It is here where mass killing becomes legally known as “genocide.” When victims are no longer seen as fully human, a steep downwards spiral starts.

If this stage is reached, then regional forces must be mobilised by the Security Council. If the conflict is beyond their capabilities, then the only option is a multilateral UN-led force. The priority becomes a matter of saving as many lives as possible whilst simultaneously ending any chance of it continuing.

10. Denial

The last of the ten stages of genocide – Denial will outlast death. Those who have committed genocide will almost never admit or recognise that they have done so. Some may deny the crimes they’re charged with, others may choose suicide over admittance. Others may even hide evidence, digging up mass graves to burn bodies and hide evidence.

In the end, Stanton’s view that popular education is the key to ending genocide is frequently echoed. Furthermore, by understanding what causes lie behind genocide, we can become more aware of its insidious nature and take preventative action before things spiral out of control.

The common vow of ‘never again’, echoed everytime an atrocity is stopped, needs to become more than a meaningless repetition. Currently, up to eighty-percent of young people don’t know about genocide, it rages on in Myanmar, and countless human rights violations in Syria and Yemen alone are cause for extreme concern. It may be one of the most peaceful times in earth’s history, but evil always progresses cunningly.