For Esther Moloto, the 32-year-old owner of a little house on top of the world’s biggest platinum reserves, the sound of progress is falling plaster.

“Before the mine came there were no cracks. Now there’s blasting every day and they are everywhere,” she says, pointing to a kitchen wall riven with fissures that she blames on underground explosions from the nearby Twickenham mine, owned by Anglo Platinum (ALPJ.J), the world’s biggest platinum company.

Moloto wants repairs and compensation — the blasting, she says, has even driven cobras into her yard from the rocky hillside behind her home. She vows in a manner typical of many South Africans to keep fighting against the unfairness of the system.

“As long as we are alive, we will pursue Angloplat to get what is owed to us,” she says, standing arms crossed on the cracked concrete veranda of her home.

Sekhukhune, a densely populated valley 250 km (160 miles) northeast of Johannesburg and famous for its platinum-rich bedrock, has a history of injustice. During apartheid, impoverished blacks were uprooted to make way for white-owned citrus farms. Now, thanks to its platinum — a metal used in some of the world’s most sought-after technologies, including ‘clean’ cars — villagers are going through a similar process to make way for mines.

Moloto’s is one of seven households in a tiny village taking on Anglo Platinum, a $27 billion (16.7 billion pounds) mining firm armed with seismic studies, teams of lawyers and assurances that local communities are “key stakeholders”. In the South Africa of old, hers might have been a straightforward hard-luck story. Nowadays, things aren’t so simple.

In November, in what may prove a landmark ruling, the country’s highest court ruled in favour of a different group of villagers who had objected to a platinum company with prospecting rights on their land.

That decision was the latest in a series of shifts — legal, government and social — designed to redress past injustices against South Africa’s black majority. Perhaps no industry more feels the heat than mining, which is still dominated by whites and still brings in billions of dollars a year.

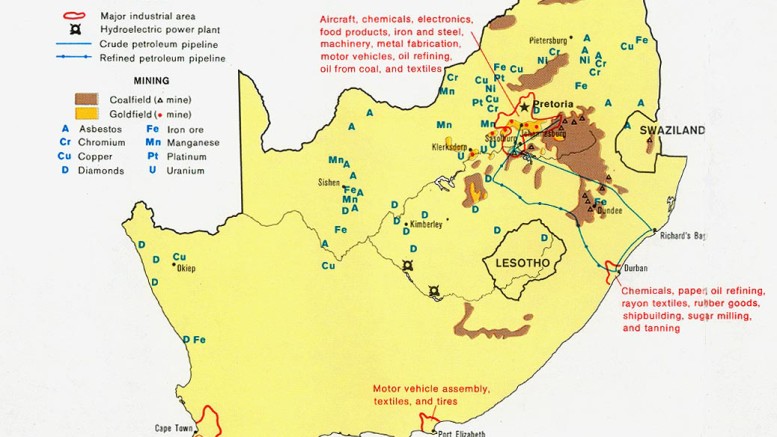

South Africa has the world’s largest gold reserves and 90 percent of its platinum, but the days when its mining houses ruled the roost are fading. While commodity prices have boomed over the past decade, mining investment in the world’s fifth-biggest mining economy has stagnated and the sector is shrinking.

Poor power supplies and infrastructure have long been a problem; of growing concern is the political climate, which now includes radical elements in the ruling African National Congress ANC.L calling for outright nationalisation of mining firms.

“At first glance, South Africa should be well-placed to take advantage of high commodity prices,” said Kevin Lings, an economist at Johannesburg-based fund manager Stanlib. “But the power, the infrastructure and the policy — when you sit around a boardroom table looking at project proposals, those are big issues.”

GOLDEN AGE

Part of the slide is the natural consequence of age.

For a glimpse of the past wealth and power of South African mining — not to mention its inequality — head for downtown Johannesburg, a city of towering brownstones built literally on gold and the sweat of artificially cheap black labour during 120 years of white domination.

At its heart sits the imposing Rand Club, built at the end of the 19th century as a watering-hole for early “Rand Lords” such as De Beers founder Cecil Rhodes, who is said to have played billiards with diamonds in its cavernous cellars. Over the years, its bar and reading room served as the de facto seat of power. With the advent of democratic rule in 1994, though, it lost its clout at a stroke and mining became an industry for the benefit all South Africans, not just the privileged few.

The decline has continued below ground, too: Johannesburg’s gold fields, the source of 40 percent of all the gold ever mined, run ever thinner and deeper. Over the last decade, output has shrunk by more than 7 percent a year, a faster decline than other mature producers such as Australia, the United States and Canada, and the trend is accelerating.

Even though South Africa is still believed to have 47,000 tonnes of gold reserves, or a global share of 12.8 percent, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, the one-time champion has slipped to third in production behind China and Australia.

That should not be a problem for a country which still has the good fortune to sit atop the world’s most valuable mineral deposits. According to a study last year by U.S. investment bank Citi, South Africa’s extant non-energy mineral wealth is $2.5 trillion — comfortably more than Russia and Australia, with around $1.6 trillion apiece.

Of these reserves, by far the most valuable is platinum, the precious metal used in gadgets such as catalytic converters and hard-disc drives, as well as jewellery. The Citi report valued the platinum deposits at nearly $2.3 trillion, reflecting the pre-eminence of a metal that now fetches $1,800 an ounce, nearly 30 percent more than gold.

Yet South Africa’s platinum sector has grown by just 4 percent a year since 1990. That’s not enough to fill the void left by declining gold production. Overall in the commodities boom that prevailed from 2000-2008, South Africa’s mining industry contracted by 1 percent every year in dollar terms, according to consultancy Global Insight. Meanwhile, mining in China grew at 19 percent a year, Russia 10 percent and Indonesia 8 percent.

With mining accounting for 8 percent of South African gross domestic product and 500,000 jobs last year, the statistics make grim reading for a government saddled with 25 percent unemployment.

POWERING DOWN

Infrastructure and power supply are both big problems. The rail network cannot get enough ore to the ocean, and the power grid struggles to meet demand. After decades of offering cheap electricity to attract investment, state utility Eskom has run out of cash to build new power stations, and prices are having to rise fast to plug the funding gap.

The government has granted Eskom three years of 25 percent power hikes and may give it another two after that, hammering margins at gold mines operating as deep as 4,000 meters underground, an engineering feat that imposes huge ventilation costs. “If they do have further large increases, it will certainly affect us badly, especially on those operations which are very deep,” says Graham Briggs, chief executive at Harmony Gold, the world’s fifth-largest producer.

Even though new power stations are being built, Eskom says supply is likely to remain tight until 2017, and many executives remember a 2008 supply crisis that brought the grid to its knees, forcing mines to stop work and costing the economy billions of dollars in lost output. The prospect of rising power costs is, miners say, a disincentive to invest in “beneficiation” — the downstream processing that should allow South Africa to export manufactured products rather than just huge quantities of raw ore, and create thousands of jobs.

“For us to be successful in beneficiation, we are going to need competitive energy rates,” said Mark Cutifani, chief executive of AngloGold, the world’s third-largest producer. “The country has to think carefully about its energy strategy. It’s inconceivable and inconsistent for us to develop and deliver 5 million new jobs if we are continuously increasing the power prices the way they are at this point in time.”

Also weighing is a chronic lack of skills in the workforce — more than half South Africa’s 500,000 miners are illiterate — making training, most notably on safety matters, very difficult. Post-apartheid laws and investment have dramatically improved a dire safety record, although 123 miners were killed last year, and the drive for “zero harm” and a safety record equal to the United States or Australia is far off both in terms of time and money.

“The mining industry is the most unskilled, uneducated group of workers of any sector in the South African economy,” said Philip Frankel, author of “Falling Ground”, a book on mine safety. “We are dealing with a lot of people who can’t understand the rules and have no particular compunction to work with the mining safety rules,” he told Reuters.

TAKING THE LOW ROAD

Compounding these practical problems is the sense of political uncertainty surrounding the ruling African National Congress ANC.L. Nelson Mandela’s liberation movement-turned-government managed to calm investors with broadly market-friendly policies throughout the 1990s, but mining’s malaise is rekindling doubts about its left-of-centre soul.

Combined with a growing whiff of corruption and the geographic proximity of Zimbabwe, it is little wonder some observers are asking whether the continent’s biggest economy is headed down the path to Robert Mugabe-style cronyism and economic anarchy.

Officially, the ANC is in no doubt about the importance of the mines. Last year it placed the sector at the heart of a plan to create millions of jobs and shift the economy up a gear from medium-paced emerging market to rip-roaring Asian-style tiger.

Yet the noises from Pretoria all emphasise a greater, not lesser, role for the state, and present little by way of concrete solutions to the power and other infrastructure problems. The strength of the rand, which has gained more than 25 percent against the dollar since the start of 2009, is another headache the industry could do without.

Of two growth scenarios painted by the Chamber of Mines in 2009 — a “high road” leading to 213,000 direct new jobs and export earnings doubling by 2020, and a “low road” of just 92,000 jobs with only a fractional increase in export receipts — few economists are betting on the high.

“Unfortunately, it’s likely to be fairly anaemic,” said Stanlib’s Lings.

“APARTHEID LIVES ON”

The concerns start at ground level, in communities like Moloto’s.

The theory was that with the end of apartheid, mining would “transform”, absorbing black capital and managers to become an engine of growth for all South Africa’s 48 million people. In reality, though, little “transformation” has happened: black ownership targets have been missed or side-stepped with marriages of convenience to political bigwigs; black managers remain the exception in an industry still run largely by the 10 percent white minority; and communities feel as alienated as they did in the past.

“We may have a black president but apartheid lives on in another form,” says 53-year-old Jerry Tshehlakgolo, a resident of Magobading, a dispiriting village of 97 homes relocated six years ago to make way for a new shaft at the Twickenham mine. “The mining companies just bribe local officials in the name of job creation. People are still being moved, apartheid-style, to make way for mining operations.”

Such views have piled political pressure on the ANC to remake mining, and last year it hardened up a target of 26 percent black ownership and 40 percent black management by 2014.

The push for black economic empowerment (BEE.L), as the policy is known, has spawned some black-run firms, but in many instances it has simply been a case of a black face on white capital. At a news conference late last year, mines minister Susan Shabangu delivered a damning indictment of BEE, saying some black bosses had no interest in running a mine and were nothing more than a front. “Some of the black economic empowerment partners who attend site visits are clueless about operations and are over-reliant on consultants — a clear case of fronting,” she said.

The risk, argues Peter Leon, a mining expert at Johannesburg law firm Webber Wentzel, is that by beefing up its goals for black ownership and management, the ANC will only invite more rule-bending and chicanery. Furthermore, it will do little to ease the concern and confusion of mining firms that have been hesitant to commit to multi-billion dollar investments that measure returns in decades, not mere months or years.

“Given South Africa’s endemic skills shortage, how are you going to have 40 percent black management at every level of a company, starting with the executive committee of the board? It seems like an impossibility,” Leon said. “On the equity side, the big mining companies will be able to achieve it but with the non-equity targets, the industry seems to have been set up for failure.”

SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL

Allegations of incompetence and corruption in the granting of mining rights are rife. The extent of the rot hit home in 2010 with a series of mining scandals that suggested at best official ineptitude, and at worst cronyism stretching to the door of President Jacob Zuma.

Fears that a rapacious political class might be abusing its power to enrich itself intensified with a second scandal at Aurora, an ailing gold mine near Johannesburg that is being run in receivership by a company operated by relatives of Zuma and of former president Mandela.

In August, four suspected illegal miners were shot dead underground and workers at the mothballed site have gone unpaid for months, incurring the wrath of unions who are adamant political connections are preventing state censure. “It’s mind-boggling. You don’t expect things like this to happen. I don’t want to use strong words like ‘failing state’, but there are signs there,” said Gideon Du Plessis, deputy-secretary general of the white-collar Solidarity union.

The various scandals prompted the government to impose a six-month moratorium on applications for new licences in September, to give it time to check 6,000 mining and prospecting rights granted since its post-apartheid minerals policy came into force in 2004. It has also promised to review laws which critics say give ministry officials too much discretion and personal leeway in granting prospecting and mining licences, often on land where people already live.

The results of the licence audit are due at the end of February; so far it has unearthed a Wild West of bribery, intimidation, illegal drilling and disputed claims.

And there are doubts the audit will clean up the licensing regime, given the ANC’s history of commissioning well-researched and hard-hitting reports only to shelve them quietly when the findings are too uncomfortable and tough to tackle.

“If they do this audit correctly, they could score major brownie points and it could be what turns it all around,” said Peter Major, a consultant at Cadiz Corporate Solutions with 28 years experience in South African mining. “But we’ve seen this sort of audit before in other departments and nothing ever seems to be done. Even if they appoint a decent committee to act on the results, it would only have a 50:50 chance of making a noticeable difference.”

“GRAVE INVASION OF RIGHTS”

Then there is ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema, who has frequently called for the mining industry to be nationalised, evoking parallels with Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe’s land grabs over the last decade.

Few people give credence to his rhetoric, especially since such a outright nationalisation could cost the government as much as $280 billion, more than annual GDP.

Yet the seeming reluctance of senior politicians, including Shabangu and Zuma, to slap him down, and the formal tabling of the issue at a major ANC policy conference last year has prompted suggestions the idea may have traction in the corridors of power. “It’s not going to happen in anything like the form being proposed by the likes of Malema. But as an investor, an assessor of political risk, you’ve got to put this on your watch list,” said political analyst Nic Borain.

“This is not a government that has shown itself to be unambitious in its involvement in the economy.”

Instead, it has fallen to the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM.L), the country’s most powerful union with a quarter of a million members and close ties to the ANC, to tackle a proposal it deems “uncooked and reckless”.

“Nobody is going to put their money in an investment when there’s no guarantee of its security,” NUM President Senzeni Zokwana told Reuters. “There’s an interest for us as a union to defend, not because we’re defending the owner but because we’re defending ourselves. You can’t find unions where there’s no employment.”

Whether or not Malema’s views carry weight, they capture the shift in the balance of power away from the mines. November’s Constitutional Court ruling has only added to the momentum. In its decision, the court overturned exploration rights to two farms held by Genorah Resources, a majority shareholder of Australia-listed junior miner Nkwe Platinum (NKP.AX), because of a failure to consult properly with locals.

Nkwe says it is confident it can convince government to let it continue prospecting, but the decision — which included a statement that prospecting rights were “a grave invasion of a property owner’s rights” — has opened the door for other disgruntled villagers to challenge mineral licences granted over land where they have lived and farmed for years.

“It’s a huge issue,” said Leon, the mining law expert. “The communities, quite rightly, are going to have to be much more extensively involved in the granting of prospecting and mining rights.”

With platinum operations springing up all over areas such as Sekhukhune, and little clarity on exactly what a “community” or “consultation” entails, the stage is set for a legal free-for-all.

“This kind of growth in the platinum sector is unprecedented and there’s no planning,” said Richard Spoor, a human rights lawyer who has represented several communities against mining firms. “We had it at the turn of the 20th century when the Johannesburg gold fields opened up; we had it in the ’50s and ’60s when the Free State gold fields opened up; now we have it in these old rural areas. History is repeating itself.”

Asked about the cracks in Esther Moloto’s kitchen, an Angloplat spokeswoman said seismic studies had shown blasting would not damage nearby houses, but the company was prepared to conduct further research and pay for repairs should it be to blame.

Such assurances are unlikely to convince Moloto or her neighbours. “They came with promises and they didn’t keep them,” said 22-year-old electrical engineering student Martin Thobejane, pointing towards a sewage plant built by the mine in a field near his home.

“Everything was cool here, and then the mine came.”

(Editing by Sara Ledwith and Simon Robinson)