Two decades after South Africa’s transition to non-racial democracy, its institutions are being sorely tested by President Jacob Zuma. Can they hold?

THE words a luta continua shine in garish orange neon from the artwork in the lobby of South Africa’s Constitutional Court. The Portuguese slogan, “the struggle continues”, was popular during the country’s fight for non-racial democracy. It remains apt. A fierce battle is now being fought for the survival of that democracy.

There has not been a coup, or anything like that. But the president, Jacob Zuma, rules in a way that perturbs even many of his former allies. Consider the events of the past week. On December 9th, without warning or explanation, he fired his respected finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, and replaced him with an obscure backbencher and former mayor so unpopular that his townsfolk had burned his house down in protests against changes to a provincial boundary.

Mr Nene’s sacking was seen as an attack on fiscal prudence. He had, for example, objected to Mr Zuma’s unaffordable plan to buy nuclear power stations costing 1 trillion rand ($65 billion) from Vladimir Putin’s Russia. It was also seen as an attempt to capture the Treasury, a part of the state that has stood firm against corruption and cronyism, by a president who has stood firm against neither.

Shortly before Mr Nene was sacked he had blocked attempts by Dudu Myeni, the chair of South African Airways (SAA), to renegotiate a deal to buy aircraft. Ms Myeni is an ally of Mr Zuma. (Indeed, she is such a close pal that Mr Zuma’s office issued a statement denying that he has a “romance and a child” with her.) Her plan was to insert a local middleman between SAA and Airbus, which was neither in the interests of the airline nor the taxpayers who guarantee its debts.

On news of Mr Nene’s sacking, the currency dropped by 9% and South Africa’s bonds posted a record slump, driving up the country’s cost of new borrowing by about 15%. After four days of panic Mr Zuma reversed course, fired his new finance minister and brought back an old hand, Pravin Gordhan, who did the job capably between 2009 and 2014.

All this left many South Africans as perplexed as they were relieved. Had Mr Zuma seen sense? Or had senior members of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) clipped his wings? Was this a triumph for democracy or a Kremlinesque subversion of it, with real power now residing behind the throne?

The great subordination

That no one knows shows how opaque the Rainbow Nation has become. This was the country that in 1994 inspired democrats the world over when it avoided a racial war, ended the world’s most notorious system of racial segregation and elected the magnanimous Nelson Mandela as its president. The flowering of freedom in a place that had seen precious little of it helped seed a great bloom of democratic change across much of Africa. South Africa’s efforts to reconcile abusers of human rights and their victims galvanised others to do the same.

South Africa’s changes ran deep. This was partly because of the ANC’s determination that the terrible abuses of human rights under apartheid would never be repeated. When talks were held on the country’s new constitution, the party was an enthusiastic supporter of limits on state power. Its view came through experience. Thousands of its supporters had been detained, tortured and killed.

After 1994 the security forces were overhauled and retrained to protect rather than oppress civilians. A parliament reserved for whites was filled with the country’s many tribes and races. A judiciary that had energetically upheld immoral laws was subordinated to a Constitutional Court sworn to protect human rights. In some ways it put more mature democracies to shame. In 1995 the court abolished the death penalty; a year later it ensured South Africa was among the first countries in the world to allow gay couples to marry.

Yet, after more than two decades in charge, the ANC’s wariness of untrammelled state power has turned into frustration at the checks on it. The party is now undermining some of the democratic institutions that it fought so hard to establish.

In 2012 the police massacred 41 striking mineworkers, shooting some in the back. In February armed police stormed into parliament to remove members of the opposition, who were heckling Mr Zuma about the colossal mansion he had built for himself at taxpayers’ expense. In June the government flouted the rule of law when it ignored an order of its own high court to detain Omar al-Bashir, the blood-soaked ruler of Sudan, for whom the International Criminal Court had issued an arrest warrant.

These examples are part of a deeper malaise. The distinction between the ruling party and the state has been eroded. The executive arm of government (and its state-owned firms) is being corroded into incompetence by corruption and cronyism. Independent bodies meant to safeguard democracy are being subordinated.

Lawson Naidoo, who runs the Council for the Advancement of South Africa’s Constitution, a pressure group, frets that the country is sliding “towards majoritarianism at the expense of principled constitutionalism”. Kgalema Motlanthe, who served as president in 2008 and 2009, recently said the ANC had abandoned its democratic principles. Desmond Tutu and F.W. de Klerk, both Nobel laureates, have lambasted the government, too. Justice Malala, a journalist and former ANC activist, summed it up well in a recent book: “One day you look around and realise that everything is broken, that your country has been stolen.”

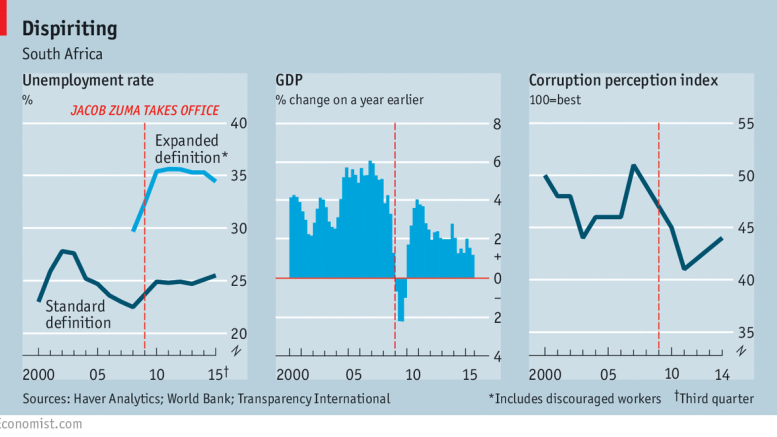

For the moment South Africans worry more about the economy than about the health of democratic institutions. Growth has slumped to little more than 1% this year, a rate that does not keep pace with the increase in population, of about 1.3%. Unemployment has climbed above 35%, if you include the millions of people who have given up looking for work.

The indebted country

Anaemic growth is largely the result of policy failures. The performance of Eskom, the state-owned electricity company, provides a useful illustration. Back in the 1990s its planners realised that it would have to build many more power stations to meet rising demand, or the country would suffer power cuts. It failed to do so. Power shortages now often shut factories and mines. Economists reckon that this has trimmed a whole percentage point a year from economic growth.

One reason why Eskom is so badly run is that many of its managers and engineers had been replaced by unqualified political appointees. This was partly owing to a policy of promoting blacks, who in some cases lacked experience. But a more pernicious subversion of meritocracy is the ANC’s insistence on appointing party hacks to senior positions. The government calls this “cadre deployment”. “I’ve said to [Mr Zuma], ‘you don’t deploy cadres to play in the national football team, so why do you deploy them to Eskom?’ ” says a grandee of African politics. “He just won’t listen.”

From unchecked power to power cuts

From unchecked power to power cutsCronyism hobbles the 700 or so firms owned by the state. Congested railways and ports—also run by state-owned monopolies—have constrained exports, trimming another percentage point or so from South Africa’s annual growth.

Stagnation, coupled with wanton spending, threatens to create a fiscal crisis. Pay for civil servants has increased far faster than inflation. Perks for ministers have ballooned. Over the past decade the number of civil servants has increased by about 25%, even as all other non-farm employment has stayed reasonably stable. A whopping one in five working people now works for the government. Over the past 15 years state spending has increased from 23% of GDP to 29%. That is dangerous in a country with a thin tax base. More than 50% of personal income tax is paid by less than 5% of taxpayers. If the country goes sour, many of these people could emigrate—as many whites already have.

Sustained deficits of about 4% of GDP mean that debt has climbed rapidly from about 26% of GDP in 2008 to almost 50% in this fiscal year. Investors fret that the country’s liabilities may soon become unsustainable. Its credit rating is one notch above junk. Without a change in course, further downgrades are likely. The ensuing sell-off would probably send interest rates soaring and force the country to ask the IMF for a bail-out.

Until recently the main reason to think that South Africa would avoid this fate was that macroeconomic policy was in the hands of a credible central bank and a sound finance minister who had pledged to contain spending. The recent game of musical chairs in the finance ministry makes many wonder if that is still true.

Rotting from the top

Cronyism and corruption are hollowing out the foundations of the state itself. Government procurement at all levels is now riddled with graft. Start with schools. Corruption Watch, an NGO, says it has received more than 1,000 reports over the past few years relating to crooked school principals, many of whom have been stealing cash from their school’s bank accounts or looting funds intended to feed hungry children. Their jobs are now so lucrative that they are worth killing for. In 2015 one head teacher was hacked to death and another was shot after they refused to make way for people who had “bought” their posts. Officials of the teachers’ union have also been implicated in selling posts. At least the bribe-takers can do sums, unlike many of their pupils. A 2011 study into the maths and science knowledge of children around the world ranked South Africa second from last.

Officials feel a sense of impunity, since few are ever fired, let alone jailed. The auditor general has given “clean” audits to less than one-fifth of local governments and a third of the national government’s departments. Some of the money set aside for Nelson Mandela’s funeral in 2013 simply vanished. “Nothing was sacred,” laments R.W. Johnson in “How Long Will South Africa Survive?”, a polemic.

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has been under sustained attack since the end of 2007, when Mr Zuma was elected head of the ANC (although he became president only in 2009). At the time the NPA had charged Mr Zuma with 783 counts of corruption, fraud, money-laundering and tax evasion. These charges were dropped just weeks before his election as president.

Since then, Mr Zuma has tried to defang the agency, usually by appointing compromised people to run it. Mr Zuma’s first appointment was subsequently ruled “irrational” by the Constitutional Court and overturned after his catspaw was caught lying to a commission of inquiry. His next appointee was forced to step down after it transpired that he had previously been convicted of assault. Many interpret Mr Zuma’s efforts to get the ANC to nominate his ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, to be his successor as an effort to ensure that his protection from prosecution will outlast his term.

Other institutions that have been tarnished include the Independent Electoral Commission. In December 2015 the Constitutional Court ruled that it had endorsed rigged local elections two years earlier. The Office of the Public Protector, an anti-corruption watchdog, is being starved of resources. Its fiery head, Thuli Madonsela, has been accused by the ANC of being “counter-revolutionary” and a CIA agent.

“Zuma has a pre-capitalist notion of power,” says one insider. “He just can’t understand why he can’t have access to state resources.” Another says that Mr Zuma complained after a tour of African capitals that his counterparts were not required to appear before parliament to answer questions. “Why do I have to?” he apparently said. His view of economics is far from the mainstream, too: he recently said that the value of commodities should depend on “the labour time taken in production”.

Given Mr Zuma’s foibles, it is unfortunate that the framers of South Africa’s constitution, for all its checks and balances, granted enormous powers to the president. “When we wrote the constitution we had in mind figures like Mandela,” says Patricia de Lille, who led the Pan Africanist Congress delegation in talks over the constitution ahead of the 1994 election and is now a leading figure in the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA).

Parliament has also proven toothless, partly as an unfortunate consequence of the transition from white-minority rule. When the constitution was being negotiated, whites worried that they would be swamped in a first-past-the-post system. So instead the country adopted proportional representation. This means that MPs owe their positions to those who draw up party lists, rather than to voters in a constituency. If they annoy the president, they may lose their jobs—and the opportunities for patronage that come with them.

That leaves the judiciary, civil society and a vibrant free press with a tradition of raking muck. The government is attempting to restrain the last of these, both with repressive laws (one act awaiting a presidential signature, for instance, threatens whistle-blowers and journalists with long prison terms) as well as more subtle means. Among these was using money from a government employees’ pension fund to help an ally of Mr Zuma buy Independent Newspapers, a large media group.

Judges are still fiercely critical of the government. The Constitutional Court often rules against the executive. Partly because the courts function so well, there has been a dangerous reliance on them to settle matters that would normally be dealt with through politics. NGOs often ask the court to force the government to provide citizens with free housing, electricity and water, for example.

Thus far the appointment of judges has remained remarkably free from political interference and the courts have been resilient. When Mogoeng Mogoeng was named chief justice by Mr Zuma, many worried that he would be a patsy. Yet he has steadfastly overseen rulings that thwart or chide the president.

A worry, though, is that the government may ignore rulings. Stuart Wilson, a lawyer at the Socioeconomic Rights Institute, an NGO that often sues the government, says it now has court orders issued against named officials rather than departments: that way, judges can hold the individuals in contempt of court if their orders are not honoured.

Yet when a court ordered the arrest of Mr Bashir, the government brazenly looked the other way as he stepped onto a plane. And at some point soon the courts are expected to rule on whether prosecutors erred in dropping corruption charges against Mr Zuma. An order to reinstate the charges and press ahead with a prosecution would “test to destruction” the constitution, says Alison Tilley of the Open Democracy Advice Centre, an NGO in Cape Town. A second case that may be as controversial is over whether Mr Zuma should be ordered to repay the state for money spent on his home (pictured).

In Nkandla did Jacob Zuma a stately pleasure-dome decree

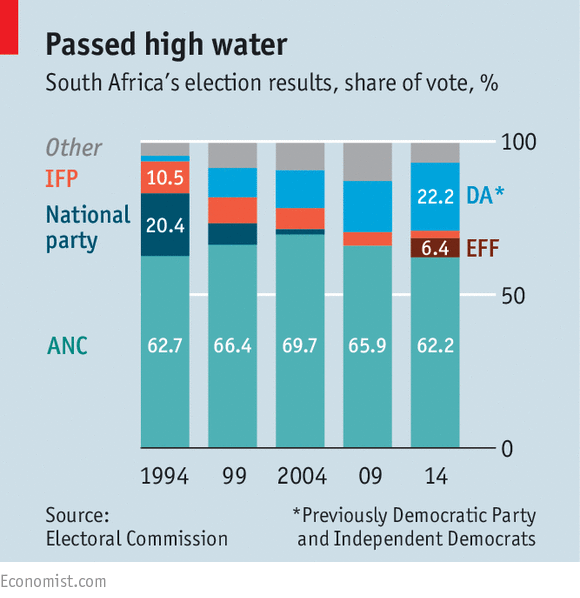

In Nkandla did Jacob Zuma a stately pleasure-dome decreeSouth Africa’s democratic institutions are battered. But as long as the courts can uphold the law there is hope that other arms of government can regain their vigour under a new and (with luck) more democratically minded president. In next year’s local elections the ANC is likely to lose its majority in most of the big cities, including Johannesburg, Pretoria and Port Elizabeth, to the DA (which won 22% of the national vote in 2014) and a newer party, the populist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), which won 6%. Mr Zuma will probably hang onto power until his second and final term expires in 2019, unless a crisis prompts the ANC to replace him with his able deputy, Cyril Ramaphosa.

The challenge for democrats will be to protect the independence of the courts and what remains of other institutions. Mr Zuma has shown an inclination to wreck them. Unless checked, the danger is that when he goes he will leave only the husk of a democracy behind.

From the print edition: Middle East and Africa

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21684146-two-decades-after-south-africas-transition-non-racial-democracy-its