15 January 2012

How the ANC Lost Its Way

By Alex Perry / Bloemfontein Monday, Jan. 16, 2012

It has been exactly 99 years and 11 months since the world’s most storied liberation movement, the African National Congress, was born, and I am looking for its birthplace. In Bloemfontein, the old Boer capital on South Africa’s central prairie, a white tourist-information officer points me to a building on the edge of town called Maphikela House — after Thomas Maphikela, who built it and who helped found the ANC. “I’ve never been there myself,” the information officer says. “It’s a township.” Then she pulls out a map and circles another part of town that I am to avoid. “Dangerous,” she says. She means “black people.”

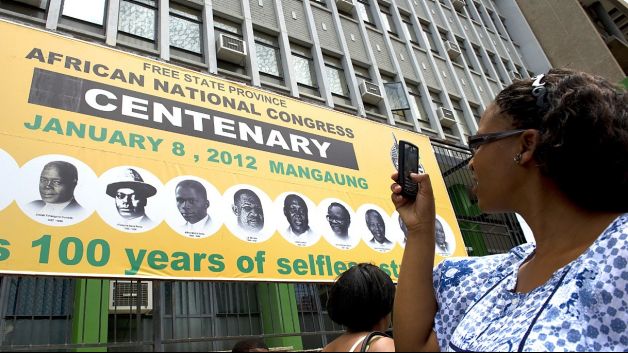

On Jan. 8, thousands of ANC supporters and 46 heads of state descend on Bloemfontein to celebrate the party’s centenary. I’ve come early to explore the origins of the organization that gave the world Nelson Mandela and laid the foundations of modern South Africa — and Africa — by inspiring the overthrow of centuries of colonialism and racist deprivation.

At least that’s ANC legend. I’m in Bloemfontein to measure that against reality. Because while South Africa has seen steady economic growth in the 17 years after apartheid, it has also experienced an abiding racial divide. That partition is expressed in enduring prejudice on both sides and persistent economic segregation. Remarkably, income inequality rose after apartheid ended: redistribution programs have mainly benefited a politically connected elite. Most whites and a few blacks live in the first world. But out of a total population of 50 million, 8.7 million South Africans, most of them black, earn $1.25 or less a day. Millions live in the same township shacks, travel in the same crowded minibuses (called taxis in South Africa) and, if they have jobs, work in the same white-owned homes and businesses they did under apartheid — all while coping with some of the world’s worst violent crime and its biggest HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The ANC blames apartheid’s legacy and, as party spokesman Keith Khoza describes it, “the reluctance of business to come to the party.” But 17 years is almost a generation. The government’s failure to transform South Africa from a country of black and white into a “rainbow nation,” in Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s phrase, means black poverty is still the key political issue. A second, related one, however, is the ANC’s dramatic loss of moral authority. At 93, Mandela is still among the most admired people on earth. But his party has become synonymous with failure — and not coincidentally, arrogance, infighting and corruption. Tutu, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and, at 80, still the nation’s moral conscience, encapsulated South African political debate last year when he came out of retirement to give two speeches. In the first he asked whites to pay a wealth tax in recognition of their persistent advantage. In the second he called the ANC “worse than the apartheid government.”

Africa is littered with liberation movements that, upon victory, forgot the people in whose name they fought. That era is coming to an end as the continent becomes more democratic and prosperous. The International Monetary Fund says seven of the world’s 10 fastest growing economies are African, despite holdovers like Zimbabwe. Is South Africa, the continent’s economic and political powerhouse, a gateway to this bright future or a window on its unhappy past?

Across the Tracks

The short drive to Maphikela house crosses South Africa’s divide. I start in leafy all-white suburbs, home to cafs, bookstores and the Hobbit Boutique Hotel, modeled on the fantasies of Bloemfontein’s most famous son, J.R.R. Tolkien. Then I cross a railway track, and I’m in the township: no trees, full of potholes and all black. Where my tourist map indicates Maphikela House should be is instead an abandoned warehouse, the windows smashed, graffiti by its broken door announcing THUG MANSION.

The local metropolitan authority says unemployment is 56%, and 59% of those with jobs earn $100 or less a month. Hanging out on a corner opposite Thug Mansion is Tumelo Lekhooe, 20, who was out of work for a year after school before finding a job as a street sweeper. “The ANC is full of corruption,” he says. “There are no good roads here, no parks, good schools or jobs. The ANC use connections to win government tenders, then spend the money on themselves.”

Lekhooe is describing a phenomenon in postapartheid South Africa: the growth of the tenderpreneur. The term describes those who get rich from government contracts or from dispensing them for kickbacks. Tenderpreneurs have turned government into a business. The national Special Investigating Unit, which targets corruption, reckons that up to a quarter of annual state spending — $3.8 billion — is wasted through overpayment and graft. The Auditor General says a third of all government departments have awarded contracts to companies owned by officials or their families; in December it found that three-quarters of all tenders in one ANC-ruled province, the Eastern Cape, rewarded officials in this way. Those being investigated for suspected corruption include two ministers, the country’s top policeman and the head of the ANC’s Youth League, Julius Malema. (All deny the charges.)

Tenderpreneurs are just one chapter in the saga of ANC scandals. There are the perks, like the $550 million the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) claims ministers and their wives have spent on themselves since 2009. There is the state security minister whose wife was convicted of running an international drug ring, and the local government minister who used public money to fly first class to Switzerland to visit his girlfriend, also in prison for narcotics. There is the previous police chief, jailed for 15 years for taking bribes from the mob. And there is a corrupt $4.8 billion European arms deal that has haunted the ANC leadership since it was agreed to in 1999.

South African President Jacob Zuma declined to be interviewed for this article, but he can be candid about the ANC’s poor record. “I have traveled to many parts of the country in recent months, monitoring the performance of government,” he said at a business breakfast in Cape Town in November. “I come face to face with the triple scourge of poverty, inequality and unemployment.” Zuma has taken action, however. He has sacked two ministers, suspended a raft of top officials, including the police chief, and set up an independent inquiry into the arms deal. He appropriated all the duties of a corrupt and inept ANC state government in Limpopo and dispatched his own officials to improve two more. He has already delivered one spectacular success to confound the skeptics: the 2010 soccer World Cup, the world’s biggest sporting event, which went off with barely a hitch.

Zuma also has a vision of how to mend the government. In November he published a 19-year national plan that identified the nation’s priorities as “corruption, divided communities, too few jobs, crumbling infrastructure, resource intensive economy, exclusive planning, poor education, high disease burden, public service [that is] uneven.” By 2030, it pledges to have created 11 million jobs, built two more universities and several railway lines, privatized power, made private business illegal for bureaucrats, deployed up to 1.3 million community health workers and facilitated the installation of 5 million solar heaters. The plan is meant to inspire a party made complacent by a consistent two-thirds electoral majority. “We are too strong,” Zuma told TIME in 2009, soon after becoming President. “You take things for granted.”

It sounds impressive. Worryingly, that may be precisely the idea. “Eleven million jobs by 2030?” asks a Western diplomat in Pretoria. “Great. Excellent. From where?” After all, Zuma has made similar commitments before. In June 2009 he promised 4 million jobs by 2014 — ambitious then, unreachable now. He also pledged 80% coverage of antiretroviral treatment by 2011 (unlikely, given UNAIDS’s figure of 25% for 2010) and an annual 7% to 10% annual cut in serious crime (against an actual 2011 — 12 fall of 5.75%). Critics say his purges of officials are less about corruption or ineptness than political vendettas.

Zuma himself is tainted by charges of corruption. He was linked to the arms deal through one of his financial advisers, who was jailed in 2005 for trying to solicit bribes on his behalf. Since Zuma was elected, the DA says the state has spent $50 million on refurbishing his homes. Tellingly, Zuma goes after those who would check his behavior. In November the ANC-led Parliament passed a law known as the “secrecy bill,” which penalizes whistle-blowers or journalists in possession of secret documents and allows no public-interest defense. He has installed unqualified allies in top positions across the justice system. Meanwhile, internal party politicking, particularly Zuma’s rivalry with Malema, has overshadowed government, something that will only increase in the run-up to a party conference in Bloemfontein in December at which Zuma is running for re-election as ANC President. “For the next 12 months, nobody will be running the country,” says Fiona Forde, author of An Inconvenient Youth, about Malema.

Mythmaking

With such an underwhelming record in office, how does the ANC win elections? By invoking its legend. The centenary celebrations, like so many other ANC events, hammer home how much black South Africans owe the party. Using such a “powerful legacy” only makes electoral sense, concedes DA leader Helen Zille. “When you’ve fought a liberation struggle and suffered so much and a party is perceived to have given you back your dignity, that party becomes who you are. How are you going to turn your back on that?” On his street corner, Lekhooe says, “I don’t know why we still vote for them,” then corrects himself. “It’s our grandparents. They say we are here only because of the ANC.”

Zille based her last general election campaign on the message that the ANC betrayed Mandela’s legacy. But how real is that inheritance? The central figure in ANC legend is Mandela, who reinvigorated the party in the 1940s and eventually led it to power in 1994. But as Mandela recounts in his autobiography, his transformation from rebel leader to global icon was, in part, a piece of imagemaking by the ANC. In 1980, after nearly four decades of fighting a regime that had not moved an inch, the party tried a new publicity strategy: personalizing its campaign with the slogan “Free Nelson Mandela.” It was wildly effective. The slogan found its way onto T-shirts and posters around the world, even into a pop song. But as it tends to, such mythmaking also distorted reality, not least in regard to Mandela’s failing marriage to Winnie. “She married a man who soon left her, that man became a myth, and then that myth returned home and proved to be just a man after all,” Mandela wrote in Long Walk to Freedom.

His remarkable ability to emerge from prison with forgiveness for his persecutors was a genuine wonder that averted a looming race war — and, for many, validated his myth. But if his reputation was merely enhanced, his party’s was whitewashed. At the time that the ANC was becoming an international cause clbre, a 1984 internal party inquiry — the Stuart Commission — found that the ANC’s training camps in Angola were “autocratic,” “corrupt” and sadistic, run through a mix of torture, rape and execution. “There was a lot of corruption, a lot of thuggery,” says Forde of the party’s years in exile, pointing also to alliances with African leaders such as Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. “You see that coming to the fore again.”

In Bloemfontein, corruption and mythmaking have combined for the ANC’s birthday party. When I eventually find Maphikela House — a grand red-brick place with two stories and a porch — the old lady who lives there directs me instead to a second building in another rundown neighborhood closer to town. In 1992, Mandela celebrated the ANC’s 80th anniversary at Maphikela House. But in 2002, National Museum historian Hannes Haasbroek discovered that the house was built in 1926, 14 years after the ANC was formed, and the party’s true birthplace was a former Wesleyan church hall a few miles away, since converted into an auto-body-repair shop. Unperturbed by this uprooting and relocating of its nativity fable, the ANC city authority promptly bought the bare-brick, wood-frame, tin-roof building and began fixing it up — at a total taxpayer cost of $4 million. Bloemfontein DA leader Roy Jankielsohn accuses the party of an “abuse of state resources.” ANC spokesman Khoza denies corruption and insists the party is paying the bulk of the centenary costs. But he sees nothing wrong with using state money to preserve the party’s history. “The ANC should be treated as part of our collective heritage as a nation,” he says.

As the Arab Spring showed, ruling parties that fail to distinguish their interests from those of the nation may also not spot their approaching fall. And the signs of the ANC’s decline are there. The party is fragmented. Its support peaked at 69% at elections in 2004 and fell to 61% at local elections in 2011. And in December it lost three previously safe seats in local by-elections. Meanwhile, the DA is growing. Its support rose from 1.7% in a general election in 1996 to 16.7% in 2009, when it also took Western Cape province, and to 23.8% in 2011. Zille says her ambition is to take two more provinces in the next general election in 2014 and the government in 2019. Like any other politician, she wants power. But she insists that removing the ANC is essential if South Africa is to finally enjoy genuine democracy. “Loyalty is a great trait, but if you are to hold political leaders to account, you can’t be loyal to a political party,” she says.

In a previous life, Zille was an antiapartheid journalist. Her ultimate goal, she says, is to make good on Tutu’s vision of a Technicolor nation. But in South Africa’s black-and-white present, Zille is only too aware that she has a “melanin deficit.” Hence moves by the DA to recruit to its leadership a black-struggle legend of its own: Mamphela Ramphele, a former World Bank managing director and long-standing ANC critic. If the name is unfamiliar, that’s because Ramphele never married her partner: Steve Biko.