Ivor Benson

The main argument which I seek to establish in this paper falls into three parts and can be summarized as follows:

- The history of South Africa, since shortly before the beginning of the Anglo-Boer War in 1899, epitomizes the history of the world over the same period.

- The world revolutionary movement which was to precipitate a century of conflict had its first clearly visible debut in South Africa, and

- The Anglo-Boer War marked the beginning of the end of the British political imperium and the beginning of an entirely new kind of imperium, that of international finance-capitalism.

We must, therefore, expect to find in the history of South Africa all the distinguishing features of conflict in most other parts of the world in our time, including propaganda as a major weapon of aggression, and the infliction of barbarities on civilian populations. The fact of the unity and coherence of the history of the world in our century is freely admitted today. Three American historians, F. P. Chambers, C. P. Harris, and C. G. Bayley, have this to say:

Two world wars and their intervening wars, revolutions and crises are now generally recognized to be episodes in a single age of conflict which began in 1914 and has not yet run its course. It is an age that has brought to the world more change and tragedy than any other equal span in recorded history. Yet, whatever may be its ultimate meaning and consequence, we can already think of it — and write of it — as a historic whole. /1 (Emphasis added.)

The “ultimate meaning” of our age of conflict which these professional historians sought in vain is more easily read out of happenings in South Africa since the 1890s than out of happenings possibly anywhere else.

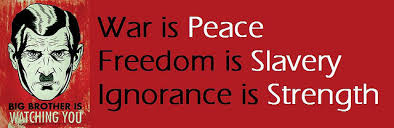

It is only to be expected, therefore, that we should find in South Africa powerful endorsement of the Orwellian dictum that forms the foundation stone of all Revisionist historical analysis: “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.” /2

Here is a sample of suppressed history which offers to throw a radically different light on the Boer War, the pivot of all Southern African history.

On December 18, 1898 — that is, shortly before the outbreak of the Boer War — one Lieutenant-General Sir William Butler wrote as follows from Cape Town to the Secretary for the Colonies: “All the political questions in South Africa and nearly all the information sent from Cape Town are being worked by what I have already described as a colossal syndicate for the spread of false information.” /3

No one was in a better position to know the truth, for General Butler was then Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in South Africa and Acting High Commissioner during the absence in England of Sir Alfred Milner (later Lord Milner), one of the principal architects and instigators of the war that was soon to follow.

Immediately after Milner’s return to Cape Town, General Butler resigned and returned to England; and successive historians have found it expedient to exclude from their writings any reference to his despatches.

General Butler, who had paid personal visits to the Boer Republic of the Transvaal, had seen for himself that the alleged “grievances” of the so-called “uitlanders,” most of them British, who had flocked to the newly discovered goldfields, were a fraudulent invention.

It is significant that there is no more than an occasional passing reference to General Butler in the official histories of that period — and to this day few students of history in South Africa would even recognize his name if they read it or heard it.

Here is another sample of the long-suppressed history of that period, a paragraph from a book written by one of the most respected writers of his day, J.A. Hobson, who had visited the Transvaal Republic before the outbreak of the Boer War:

We are fighting in order to place a small international oligarchy of mine-owners and speculators in power in Pretoria. Englishmen will do well to recognize that the economic and political destinies of South Africa are, and seem likely to remain, in the hands of men, most of whom are foreigners by origin, whose trade is finance and whose trade interests are not British. /4

It says much for Hobson’s powers of perception that in another book, The Psychology of Jingoism he was able to present an analysis of propaganda and disinformation which bears comparison with George Orwell’s masterly study of this subject in his Nineteen Eighty Four.

Another writer of that time who seems to have escaped the attention of historians was L. March Phillips, an officer in Rimington’s Scouts, who had worked in the Transvaal for several years before the war. This is what he wrote:

As for the uitlanders and their grievances, I would not ride a yard or fire a shot to right all the grievances that were ever invented. Most of the uitlanders (that is, miners and working men on the Rand) had no grievances. I know what I am talking about for I have lived and worked among them. I have seen English newspapers passed from one to another and laughter raised by the Times telegrams about those precious grievances … We used to read the London papers to find out what our grievances were, and very frequently they would be due to causes of which we had never heard. I never met one miner or working man who would have walked a mile to pick a vote off the road and I have known and talked with scores of hundred. /5

These were not the views of men habitually critical of the British Empire. General Butler had served the Empire loyally and with distinction in India, Egypt, Canada, West Africa and elsewhere. And Hobson was one of the many great Englishmen of his time who, like Edmund Burke before him, could happily identify themselves with the Empire’s role in history.

What Butler, Hobson and other critics of the Milner policy saw in South Africa was something new and unprecedented: fraudulent misrepresentation on a colossal scale used by British leaders against their own people and their own parliament as a means of drawing them into a planned war.

Dishonorable conduct was being used for the first time as an instrument of imperial policy.

A revised history of South Africa which is now beginning to emerge exposes the enormity and impudence of the falsehood then used-and which is again being used in a renewed onslaught against the people of South Africa.

The biggest breakthrough for honest historical reporting came in 1979 with the publication of Thomas Pakenham’s well-documented and richly illustrated book The Boer War, in which we read as follows about the causes of the war:

First there is a thin golden thread running through the narrative, a thread woven by the ‘gold bugs,’ the Rand millionaires who controlled the richest gold mines in the world. It has been hitherto assumed by historians that none of the ‘gold bugs’ was directly concerned in making the war. But directly concerned they were … I have found evidence of an informal alliance between Sir Alfred Milner, the High Commissioner, and the firm of Wernher-Beit, the dominant Rand mining house. It was this alliance, I believe, that gave Milner the strength to precipitate the war. /6 (Emphasis added.)

Pakenham lays bare the real motives at work in precipitating the Boer War but does not fit the facts into a coherent interpretation of the history of South Africa that will absorb and explain some of its glaring paradoxes:

- How was it possible for methods to be used in precipitating the war which shocked many old and trusted servants of the British Empire?

- How was it possible in 1907, so soon after a long and bitter war, for General Louis Botha, then prime minister of the Transvaal colony, now British, to be so much in love with the Empire that he could make a present of the famous Cullinan diamond to King Edward VII?

- How was it possible for General Smuts, first prime minister of the Union of South Africa, to bring both the English South Africans and the Afrikaners into World War I on the side of the British?

- Even more paradoxically, how was it possible for an English oriented South African Labour Party to help overthrow the pro Empire Smuts government in 1924 and virtually reverse the verdict of the Boer War by putting an Afrikaner nationalist party in power?

These are questions we shall need to be able to answer if we are to understand the history of South Africa and the present rapidly mounting undeclared war against that country.

The situation in which the people of South Africa find themselves today is in many ways similar to the situation in which the Transvaalers found themselves in the years preceding the Boer War.

Then it was the alleged denial of political rights to the English speaking “uitlanders” which served as ammunition for massive hate propaganda and pressure, and as casus belli. Today it is the grievances of the Blacks which are called on to supply the propaganda ammunition and justify internal revolutionary activity, most of it masterminded and financed from abroad.

In the 1890’s, as also today, demands for so-called reforms were of a kind clearly aimed not at reform but at the complete displacement of the country’s existing rulers.

One big difference is that in the 1890’s the Transvaal’s enemy was Britain, whereas today South Africa finds itself apparently in confrontation with the whole world; and another difference is that Afrikaners and English-speakers today find themselves equally endangered.

The maximum deployment of all the forces of parliamentary politics since the end of World War II having failed to dislodge Afrikaner nationalism from its position of power, what we now see is, in effect, a renewal and resumption of the Boer War.

Before we go on to seek a broad explanation of all this, it might be well to examine briefly the allegation that it is the unredressed grievances of the Blacks which lie at the root of all the present troubles and which call for intervention from abroad.

Substantially, the reasons given for the present world condemnation of South Africa are just as spurious as those given by Milner and his associates for hostility towards the Kruger government in the Transvaal.

It is true that there is much discontent among South Africa’s Blacks, as there is discontent everywhere else in the world where Blacks find themselves in a human environment which is not of their own making. There is bitter discontent among Blacks in the United States, in Britain, and elsewhere in the West, exploding from time to time into violence and destruction. /7 Black discontent is something for which no remedy can be found even inside the British Labour Party, one of South Africa’s most vehement critics, as Black members continue to defy their leaders and demand “apartheid” in the form of separate branches of their own.

There is Black discontent in South Africa it is true, but evidently even more of it across that country’s borders — for how else has illegal Black immigration become one of South Africa’s major problems?

It is also necessary at this point to expand a little on the subject of the “golden thread” which Pakenham found running through the story of the Boer War and its causes-that “international oligarchy of mine-owners and speculators” of which Hobson writes.

The funding which enabled Cecil Rhodes to consolidate his grip on the diamond mining industry was supplied by the British branch of the Rothschilds, but most of the Transvaal’s financiers came from the continent.

The mining groups listed by Hobson include Wernher, Beit and Company, with 29 mines and three financial companies; but even this great group he found to be only the leading member of “a larger effective combination” which included, for all practical purposes, Consolidated Goldfields, S. Neumann and Co., G. Farrar, and Abe Bailey. Goldfields (virtually Beit, Rudd, and Rhodes) owned 19 mines. Hobson traces some of the lines of financial control to Rothschild and the German Dresdner Bank in which Wernher and Beit had substantial holdings.

In a chapter headed “For Whom Are We Fighting?,” Hobson declares that even at the risk of seeming to appeal to “the ignominious passion of Judenhetze,” he found it a duty “not to be shirked” to point out that “recent developments of Transvaal gold mining have thrown the economy of the country into the hands of a small group of international financiers, chiefly German in origin and Jewish in race.”

In this scenario, as Hobson shows, Cecil Rhodes, the arch-imperialist and empire-builder and main instigator of the Boer War, figures as no more than a small planetary wheel in a vast international financial machine which he, no doubt, believed he had harnessed to his grandiose imperial purposes.

For General Butler, also, the duty of identifying what he called “the train-layers setting the political gunpowder” was not to be shirked. In a despatch to the War Office in June 1899 he wrote: “If the Jews were out of the question, it would be easy enough to come to an agreement, but they are apparently intent upon plunging the country into civil strife … indications are too evident here to allow one to doubt the existence of strong undercurrents, the movers of which are bent upon war at all costs for their own selfish ends.”

For the people of Britain, the Boer War was a traumatic experience. A war that was expected to last only a few weeks dragged on for nearly three years and could only be brought to an end by an application of draconian measures which produced reactions of revulsion at home. The cost of the war also came as a shock: 350 million pounds — a great deal of money in those days — and 20,000 soldiers’ lives. /8

The trauma had something to do with the moral aspects of the struggle; it is one thing to fight against a dangerous enemy who threatens a nation’s existence, quite another to suffer a succession of reverses with appalling losses of life in what is plainly a European fratricidal struggle for reasons which become increasingly dubious with the passage of time.

Paradoxically, too, a struggle which was to be labelled “the last gentlemen’s war,” in which there were continual displays of chivalry on both sides on the field of battle, was characterized also by reversions to barbarism, involving non-combatants.

Kitchener’s scorched-earth policy, the only means by which Britain could be extricated from an intolerable situation, reduced the whole of the Transvaal and Orange Free State to a wilderness of devastated farms and uncultivated fields, and resulted in the death of more women and children in his concentration camps, mostly from typhoid, than there were men killed on both sides in the actual fighting. /9

As was only to be expected, the intoxication of patriotism — Hobson called it “jingoism” — with which the war was launched and promoted was followed in Britain at the war’s end by the moral equivalent of an acute hangover.

In the post-war general election, the Unionists — the “victorious” party — were defeated and a Liberal Party government under Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman proceeded to treat the conquered Boers with the utmost kindness and consideration. The two Boer republics became British colonies but with wide powers of self-rule; and the stage was set for the introduction of a party political process — “war by other means” — which has continued to this day. /10

The rest of the South African story is about the reasons why the new policy of conciliation was doomed to fail.

Or, to put it differently, the political history of South Africa for more than 50 years after the Boer War can be said to have revolved around two mutually antagonistic perceptions of the British Empire or British connection.

The British Empire had acquired a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde split personality, by some encountered as a model of respectability and virtue and by others as a monster of iniquity.

The Empire ideal, as verbalized with great power and eloquence by John Ruskin and Rudyard Kipling, had something in common with the socialist ideal by which it was due to be replaced later as an intellectual frame of reference and motivating system of ideas; for socialism, too, was destined to acquire a double character, loved by some and abominated by others. /11

How is all this to be explained?

At a time in the history of the peoples of the West when a vacuum had been created in the minds of men by a new “enlightenment” which devalued the old religious orthodoxy, a secular Empire ideal dike socialism, a programme for world improvement) was found to serve quite well as a substitute for the abandoned religion; for it supplied a sense of purpose and direction and a coherent and self-explanatory intellectual frame of reference. That was the sunnier side of the “ideal,” symbolized by Dr. Jekyll.

The dark side of the ideal was to be found in what some men were prepared to do in its name and for its furtherance.

The shock which ended General Butler’s career in South Africa was experienced by him as the betrayal of an ideal which had hitherto served him unfailingly as a lodestar; the methods used by Rhodes and Milner and their circle were, from his point of view, decidedly not “British,” and policies designed to precipitate a war with the Transvaal Republic were, for him, clearly not in the British interest.

It had been possible for several generations of Englishmen, products of the best schools and universities, to reconcile the conduct of imperial affairs with the preservation of standards of personal conduct which drew the clearest distinction between the “cad” and the “gentleman” — a state of affairs nowhere better illustrated than in Edmund Burke’s impeachment of Warren Hastings.

What Butler saw in Cape Town was the employment of dishonorable means for the attainment of the most dubious ends.

The appeal of the Empire ideal, or “English idea” as it came to be called, was by no means confined to the British; it had its votaries on the other side of the Atlantic, as Dr. Carroll Quigley has shown in his “history of the world in our century,”Tragedy and Hope. /12

And Boer leaders, like General Louis Botha and General Smuts, when the fighting was over and a generous policy of conciliation was being applied by the victors, were not immune to the charms of an ideal which offered glowing possibilities for the future of mankind; moreover, it had much to show for itself wherever the Union Jack had been planted. Botha and Smuts were wholly won over; and Smuts figured from 1914 onwards more as an Imperial statesman than a South African party political leader.

That partly explains why Botha, on behalf of the Transvaal colony, was able to make a gift of the Cullinan diamond to King Edward VII and why, in 1914, he was able to crush a rebellion of Boer “bitter-enders” and bring South Africa into World War I on the side of Britain.

A split in South African politics came shortly after the formation of the first government of the Union of South Africa in 1910 with the resignation from Botha’s cabinet of another former Boer leader, General J.B.M. Hertzog. Hertzog launched the National Party, and a pattern of party political strife was initiated that was to continue to this day.

Now let us examine more closely that negative perception of the British connection, or “English idea” as it came to be called in the United States, which formed the basis of Hertzog’s political thinking, and that of a succession of other National Party leaders, including Dr. Daniel Malan, Mr. J.G. Strijdom and Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd.

It is significant that hatred of the ethnic “English” was never an important component of Hertzog’s negative attitude towards the British connection, nor the main reason for a resurgence of Afrikaner nationalism. Hertzog’s Christian names “James” and “Barry” provide some evidence of his parents’ response to English influence in the Cape Colony, Barry being the name of the much loved English doctor who had attended at his birth.

The perceived enemy of the Afrikaner, from the very beginning, was not “die Engelse” but “die geldmag,” or “money power,” symbolized in Afrikaner folklore as “Hoggenheimer,” the stereotype of the mining financier. It was also fear and hatred of financiers — Pakenham’s “gold bugs” — which motivated the armed rebellion in 1914, triggered by Botha’s decision to join Britain in declaring war on Germany.

On the positive side, what motivated Hertzog was the ideal of the unity of the two language groups in a shared patriotism under the slogan “South Africa First,” a policy which took care not to disturb the cultural integrity and unity of either group — something like the patriotism that has prevailed in Switzerland and Belgium. This he called his “two stream policy.” His attitude towards the “English” in South Africa was, therefore, always frank and honorable.

That helps to explain how it was possible in 1924 for an English-oriented South African Labour Party to join forces with Hertzog’s National Party against a Smuts government which had so recently helped Britain to win the war against Germany.

The trouble began with the mine-workers on the Witwatersrand, whose accumulated grievances at the hands of the great mine-owners finally exploded in the Rand Rebellion of 1922. General Smuts, who had become prime minister after the death of General Botha in 1919, used troops, artillery, and even bombing by aircraft to crush this rebellion. Smuts had come down firmly on the side of the mine-owners, and the mine-workers were left worse off than ever.

Workers all over the country were infuriated and rallied to the support of the two opposition parties in parliament — the Afrikaners to the National Party and the English-speakers to the Labour Party. The two opposition parties then formed an alliance, and in the elections of 1924 the Smuts government was defeated.

But did this amount to an actual reversal of the verdict of the Boer War? Not quite. Constitutionally, South Africa remained a component of the British Empire, or Commonwealth of Nations, as it came to be called, under a governor-general appointed by the monarch; and South Africans were still British citizens carrying British passports.

What many would have found it hard to understand was the fact that this radical change in the course of South African history had been accomplished with the whole-hearted assistance of the English-speaking supporters of the Labour Party, a few of the older ones actual “uitlanders” of the former Republic for whose supposed “liberation” from Afrikaner domination the Boer War had been fought. Those English-speakers who helped the National Party to get into power also included many who only a few years before had been fighting for Britain on the battlefields of France and elsewhere.

The result of all this was a most unusual political phenomenon: a nationalist Afrikaner South Africa tacitly accepted by a substantial English-speaking population, while still held on a slender constitutional lead by the ruling powers in Britain.

The nationalist government proceeded at once to give effect to Hertzog’s policy, replacing as quickly as possible some of the symbols of a subordinate association with Britain, including the flag, and drastically Afrikanerising the civil service, army and police-with little or no opposition from the Labour Party’s “English” representatives in Hertzog’s cabinet.

If we can get our central historical thesis right, we can expect the facts to continue to fall into place.

Policies aimed at making South Africa increasingly independent and self-directed always enjoyed the silent support of the English-speakers, who felt equally threatened by policies promoted in the name of opposition to Afrikaner nationalism.

In particular, there has been almost unanimous support down the years for policies designed to keep political power in White Afrikaner hands. In other words, unity of understanding and of purpose in race matters has been strong enough to prevail over all the inconvenience and irritation suffered by the English under an exclusively Afrikaner administration.

It is for this reason that those who continued to promote internal revolutionary activity against Afrikaner nationalism were able to draw very little assistance and support from the broad stream of the English-speakers; hence, too, only the Blacks were available in any number as revolutionary fodder.

The story of opposition politics in South Africa is told with surprising candor by Dr. Gideon Shimoni in his well-documented book Jews and Zionism: The South African Experience 1910-1967. /13

Shimoni writes of the period following World War II: “Jewish names kept appearing in every facet of the struggle; among reformist liberals; in the radical Communist opposition; in the courts, whether as defendants or as counsel for the defence; in the list of bannings and amongst those who fled the country to evade arrest. Their prominence was particularly marked in the course of the Treason Trial, which occupied an important place in the news media throughout the second half of the 1960s. This trial began in December 1966 when 156 persons were arrested on charges of treason in the form of a conspiracy to overthrow the state by violence and replace it with a state based on Communism. Twenty-three of those arrested were Whites, more than half of them Jews.” /14

After naming some of the Jews involved, Dr. Shimoni goes on: “To top it all, at one stage in the trial the defence counsel was led by Israel Maisels, while the prosecutor was none other than Oswald Pirow. The juxtaposition was striking: Maisels, the prominent Jewish communal leader, defending those accused of seeking to overthrow White supremacy.”

Dr. Shimoni remarks that when the secret headquarters of the Communist underground was captured intact by the police at Rivonia, near Johannesburg, in 1964, five Whites were arrested, all of them Jews, and he names them: Arthur Goldreich, Lionel Bernstein, Hilliard Festenstein, Denis Goldberg, and Bob Hepple. The expensively equipped Communist command post was situated in a luxury house in extensive grounds, owned by another Jew, Vivian Ezra.

There is no need for an analysis of the relationship of the English language mining press and the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary movement, for a statement by Abram Fischer, leader of the South African Communist Party underground, says it all: “A section of our press is doing a magnificent job.” It was revealed at Fischer’s trial in 1965 that these words, referring to this English-language press, formed part of a progress report which Fischer had prepared for his comrades.

So, now we know what it was that made the two perceptions of the Empire, or British connection, so different.

Botha and Smuts saw it in its original idealized form, as the philosopher John Ruskin may have seen it; Hertzog, Malan, Strijdom and Verwoerd saw it as it actually was-an Empire that was undergoing a mysterious change of identity, an Empire that had come under the influence of forces and motives very different from those which had attended its creation, an Empire which had begun to embrace a radically different system of ethical values.

The story of Hertzog’s career until his displacement by Smuts on the outbreak of World War II can be summarized as follows:

Hertzog took a lead at the conferences of Commonwealth prime ministers in London in securing radical constitutional changes, culminating in the Statute of Westminster in 1932 which, if it did not free the dominions entirely, gave them the right to decide whether to stay in the Commonwealth or get out.

Feeling that his main objective had been attained, Hertzog agreed to join Smuts in a “government of national unity” as a response to the challenge of the economic depression then prevailing. Most of the nationalists supported Hertzog in an electoral alliance with Smuts’s South African Party, but many broke away when the two parties fused to form the United Party. These dissidents under the leadership of Dr. Malan then took over the “National Party” label.

Hertzog opposed South Africa’s entry into World War II but was narrowly defeated when the issue was put to the vote in Parliament. Hertzog resigned and Smuts took over. However, in the first general election after the war’s end, Dr. Malan and his National Party, revitalized by its role as wartime opposition, was swept back into power — again with slogans about “die geldmag,” or money power.

From the vantage point of 1986, we can now see that the history of South Africa in this century has a meaning very different from that which was previously read into it. It never was a struggle between “Boer and Brit.” For where now is that Empire which Ruskin, Rhodes, Milner and Smuts dreamed of as the foundation of a new world order? It has passed away, to be replaced by the grotesque caricature of a “New Commonwealth.”

And what happened to that little country in Central Africa which was to have been an everlasting memorial to Cecil John Rhodes, one of the founders and architects of the Empire? The statue of Rhodes in imperishable bronze was cast down from its granite plinth in Jameson Avenue, Salisbury, and the whole country purged of all associations with the Empire-builders.

But it is not only in Rhodesia that this change of attitude has occurred; all establishment or consensus thinking — that is, thinking among those who rule in the world — has been purged of any associations with the British Empire as a ground plan for the future of mankind.

We can now see more clearly than was possible in 1898 that the alliance between Milner and the so-called “gold bugs” of the Witwatersrand, most of them of foreign origin, was the beginning of the end of British power in the world, and the beginning of a struggle which Professor P.T. Bauer has so aptly described as “an undeclared one-sided civil war in the West.” /15 Concerning this struggle, Solzhenitsyn has written as follows:

“We have to recognize that the concentration of World Evil and the tremendous force of hatred is there, and it’s flowing from there throughout the world. And we have to stand up against it, and not hasten to give to it, give to it, give to it, everything that it wants to swallow.” /16

All the signs of what was happening in South Africa since before the beginning of the century can, therefore, be understood only in the context of what was happening, and continues to happen, all over the world. In the words of the three historians earlier quoted, our “age of conflict” must be considered as an “historic whole,” presupposing the existence of “some ultimate meaning.” Or, to put it differently again, the immediate and obvious causes of the major changes which constitute South African history find their full meaning only as part of the “ultimate meaning” of our age of conflict.

What precisely was the cause of the mysterious change of identity which preceded the British Empire’s dissolution and its replacement with a socialist ideal and a new and unprecedented world imperium of high finance? The change which was to produce a worldwide chain-reaction of other change, starting with the British Empire, can be said to have begun in the realm of high finance shortly before the turn of the century.

Before then, high finance — not to be confused with private ownership capitalism — existed in great national concentrations, each one largely geared to a national set of interests. There was a British finance-capitalism, then the most powerful in the world, a German finance-capitalism, an American finance-capitalism, and so on.

There had always existed also an international high finance operated by great banking families or dynasties, the most famous of these being the Rothschilds. These all formed part of the national concentrations of financial power but were able to operate with varying degrees of success across national frontiers.

The great change came, unannounced and unreported, when these international banking families were able, by joining hands, to bring all the national concentrations of financial power into coalescence, increasingly under their power.

High finance became fully internationalized. A new world imperium was established. A new kind of Caesar came to power in the world. /17

The clearest documentary evidence in support of this interpretation of history will be found in Professor Carroll Quigley’s monumental history of our century, Tragedy and Hope.

Some historical changes are unrecognizable when happening, yet noticeable after they have happened. The fact that powerful international banking families had long been established in Britain and even formed part of the nobility would have made it even more difficult at the time to penetrate the mystery.

It is now obvious that the assistance which financiers like Rothschild, Beit and Wernher so willingly gave to Cecil Rhodes and Alfred Milner had long-range purposes very different from the purposes of these two enthusiastic British race-patriots. What these financiers were, in fact, doing was to initiate a shift of the centre of gravity of world power away from the different nations of the West towards a new imperialism.

Rhodes and Milner, we may be sure, confidently believed that they were harnessing these financiers to the chariot of their political ambitions, but events have shown that these financiers, organized increasingly on a global basis, had political ambitions of their own.

And it was because the real power had begun to flow from this new centre that British public affairs began to exhibit signs of a different morale in which little value, if any, is attached to airy realities like those of personal honour and truthfulness. In other words, there was a moral transformation involved in a change which began to permit pure finance to prevail over national politics.

No one exemplified this moral transformation better than Cecil Rhodes himself with his well-known axiom, “every man has his price” — a corrupting influence which he did not hesitate to exercise within his own community for the attainment of ends he believed to be good.

This interpretation is strongly endorsed by everything that has happened in South Africa since the National Party was restored to power in 1948.

More obviously than ever after the fall of Rhodesia, English-speakers in South Africa have felt very deeply the need to depend on Afrikaner solidarity for their preservation against a similar disaster. Hence nothing could have been less British or English than the massively financed campaign of subversion and urban guerilla warfare which has been so conspicuous a feature of the post-World War II years in South Africa. /18

So, it is now the question of South Africa’s fitness to survive which must engage our attention. Are the Afrikaners as solidly united today as in 1948 and thereafter under Dr. Malan, Mr. Strijdom and Dr. Verwoerd?

There can be only one answer to that question: No! At a time when solidarity is most needed, Afrikanerdom is sharply divided. The government has moved to the left and is being opposed with great vehemence by a revived nationalism led by Dr. Andries Treurnicht’s Conservative Party and Mr. J.A. Marais’s Herstigte Nasionale Party.

What happened to bring about this major disturbance of Afrikaner solidarity can be explained quite simply. After 1938 there came rapidly into existence an Afrikaner moneyed elite whose declared purpose it was to secure for the Afrikaners a larger stake in the nation’s economy. This new moneyed elite with its own investment houses, banks, building societies, etc., prospered enormously by exploiting a highly inflated nationalist sentiment; so much so that by 1965 these wealthy Afrikaners felt strong enough to break into the magic circle of mining high-finance. In fact, an opening had been made for them — a trap into which they fell most readily in spite of warnings by Dr. Verwoerd and others. An important part of Afrikanerdom entered into an alliance with the traditional enemy, “die geldmag” or money power, and could no longer fight it because inseparably joined to it with veins and arteries of shared interest — including, of course, a shared attachment to the principle of credit financing by which they were doomed sooner or later to be yoked. /19

The existence of this partnership in high finance will help to explain why South Africa’s present strategy has been based almost exclusively on principles of appeasement and accommodation.

What then are the prospects for South Africa?

The South Africans are in much the same situation as the Trojans at the siege of Troy; the Trojans could not have defeated the Greeks in battle — but they could have won if they had not allowed themselves to be tricked into defeat. Like the Greeks who surrounded Troy, those now waging an undeclared war against South Africa, maintaining as it were a state of siege, are falling increasingly into disorder and disarray. The new world order which they are trying to build can now be seen as a Tower of Babel which is bound to collapse about their ears sooner or later. They are having to pay an enormous price for being out of register with reality.

Thus, whether South Africa survives or not may depend on two questions which the future will answer:

- Will the South Africans be able to resist the temptation of a “settlement” of the kind that beat the Rhodesians?

- Will enough of the history of this century be known to enough people in the West to collapse that “Tower of Babel” while the South Africans are still holding out?

Meanwhile, is there nothing South Africa’s rulers could do to hasten the collapse of that “Tower of Babel”? Is there no alternative to a strategy of endless conciliation, negotiation, and accommodation? Many of South Africa’s friends, especially in the United States of America, have answered “Yes!” to such questions but their suggestions have been ignored — just as the suggestions of Rhodesia’s friends around the world were ignored.

The Republic of South Africa, armed with full knowledge of the forces and motives involved in the present struggle, and the skill with which to make the best use of that knowledge, could be a far more formidable opponent than the little Boer Republic at the turn of the century.

One of the major factors in South Africa’s present position of strength is the vulnerability of all the political regimes in the West, which have joined hands with the Soviet Union in the present undeclared war aimed at grabbing political control of an area of immense strategical importance and one of the world’s greatest repositories of mineral wealth. Their vulnerability exists mainly in the realm of public opinion — as demonstrated in 1965 when the peoples of the West responded instantly and spontaneously to Rhodesia’s declaration of independence by setting up innumerable “Friends of Rhodesia” organizations; this public response caused great embarrassment to those Western governments which had joined the Soviet Union and Red China in promoting revolutionary change in Central Africa, and would have expanded enormously had it not been discouraged by an Ian Smith government bent on achieving what it was pleased to call a “settlement.”

There can be no doubt that a resolute stand by South Africa, supported with skilful deployment of the country’s considerable resources, could deliver a staggering blow at that conspiratorial “network” so accurately described by Professor Carroll Quigley in his book Tragedy and Hope.

Millions of concerned people in the countries of the West are just waiting for some nation to raise the counterrevolutionary standard with a cry that will ring around the world: So far and no further!

South Africa with its vast resources in strategic and other minerals, its manufacturing potential, its ability to feed its own people, and a military power, both conventional and nuclear, without equal in Africa, is one of the few developed countries capable of severing links of dependence on the rest of the world and of adopting a bold and heroic attitude — for the benefit of the whole of the West.

South Africans should be further strengthened in a resolution to resist by the knowledge that a willingness to negotiate will win them no remission of the penalties of defeat — as the Rhodesians earlier learned to their sorrow.

This, then, is the message I bring from South Africa: The peoples of the West have allowed themselves to be drawn into yet another of this century’s fratricidal struggles. That is the meaning of what those history professors call “this century of conflict.”

Notes

- F. P. Chambers et al., This Age of Conflict (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1943).

- George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1949).

- Lt. General Sir William Butler, An Autobiography (Constable, 1911).

- J. A. Hobson, The War in South Africa (James Nisbet, 1900).

- L. March Phillips, With Rimington in South Africa.

- Thomas Pakenharn, The Boer War, 1979.

- See Behind the News, October 1985, “Britons Shaken as Riots Spread.” 8. H. Rider Haggard records that Sir Abe Bailey, one of Rhodes’s closest associates, when reminded of the cost of the war to Britain in lives and money, replied: “What matter? Lives are cheap”; in the Cloak That I Left, a biography, by Lilias Rider Haggard (Hodder and Stoughton).

- See Arthur Davey, The British Pro-Boers 1877-1902 (Tafelburg); S.B. Spies, Methods of Barbarism? (Human and Roussouw); Douglas Reed, Somewhere South of Suez (Jonathan Cape and Devin-Adair); and books by Deneys Reitz, and by the Boer War hero General Christian de Wet.

- See Chapter 1, “This Worldwide Conspiracy,” in The Battle for South Africa, Ivor Benson (Dolphin Press).

- The difference between British imperialism until the turn of the l9th century, and socialism since the end of World War I, is not simply a difference of political theory; it was the voices of the blood which supplied the original ideas of Ruskin, Rhodes, and Milner with a powerful energizing principle. But as it turned out, race-patriots like Rhodes and Milner were not sufficiently armed with insight, intelligence, and money to win the ensuing struggle. See alsoThe Battle for South Africa. on. cit.

- Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (New York: Macmillan Co., 1966).

- Dr. Shimoni’s account of opposition politics in South Africa may be compared with that of Dr. B.A. Kosmin for Rhodesia, Majuta: A History of the Jewish Community in Zimbabwe (Mambo Press, Zimbabwe), equally candid; Shimoni’s book is published by Oxford University Press.

- Detailed information about the South African treason trials is given in Traitor’s End by Nathaniel Weyl (Tafelberg).

- P.T. Bauer, Equality, the Third World and the Economic Delusion (Weidenfeld and Nicolson).

- From Solzhenitsyn’s address to the leadership of the AFL-CIO in Washington, D.C., 30 June 1975.

- This thesis of the revolution in the realm of high finance was first published in the present writer’s pamphlet, The Middle East Riddle Unwrapped (1984), and has been further developed in his book The Zionist Factor (Veritas).

- See the present writer’s pamphlet Behind Communism in Africa (Dolphin Press, 1975).

- See Behind the News, January 1979, “The Broederbond Boss Speaks”; February 1983, “Mr. Heunis Unveils Government Thinking”: July 1985, “South Africa: Politics of Confusion.”

Further Reference: In addition to works cited in this paper, detailed chronological sequences of political affairs in South Africa since the Anglo-Boer War will be found in A History of Southern Africa by Eric A. Walker (Longmans Green), and 500 Years: A History of South Africa, edited by Professor C. F. J. Muller (Academia, Pretoria).

From The Journal of Historical Review, Spring 1986 (Vol. 7, No. 1), pages 5-20. This article is adapted from a paper Presented to the Seventh International Revisionist Conference.

About the Author

Ivor Benson is a South African journalist and political analyst. He wrote for the Daily Express and Daily Telegraph in London, and later was chief assistant editor of the Rand Daily Mail. From 1964 to 1966 he served as Information Adviser to Ian Smith, Prime Minister of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Mr. Benson has lectured on four continents.