When the term Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) first floated into the South African business and political lexicon in the early 1990s, there was some hopeful discussion that it would last just 20 years and then be phased out.

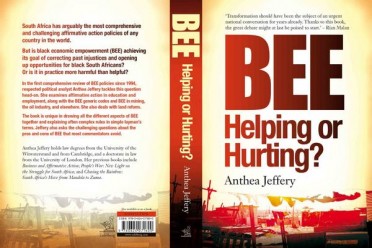

In the foreward to Anthea Jeffery’s book BEE: Helping or Hurting?, author Rian Malan writes that most journalists missed the most important story of the post-apartheid era. “By the time I reached the halfway mark I was trembling with outrage and bombarding friends with distressed SMSes and emails. Are you aware, I said, that the ANC government has drawn up a ‘final policy proposal’ allowing it to expropriate 50 per cent of farmland without compensation being paid to the farmers concerned? And that the Constitutional Court has already given its indirect blessing to such a move?”

South Africans of every colour need to face up to some harsh realities: white South Africans need to admit that they unfairly benefited from apartheid race laws that kept blacks out of the race; black South Africans need to recognise that the laws being drafted by this government in their name have the capacity to destroy our society “just as surely as the Xhosa nation was destroyed by the Great Cattle Killing of 1856 to 1957.”

There’s a whole library of laws on the table that will empower the government to plunder pretty much what it likes: the Expropriation Bill, empowering “thousands of officials at all three tiers of government to expropriate property of virtually any kind”; the Protection of Investment Bill of 2013, which denies foreign investors the right of international arbitration in the event the government decides to seize their assets; the Mining Amendment Bill, which gives the government the right to take control of privately-run oil and gas fields for whatever compensation it likes.

The consequences of BEE and associated laws are slapping us in the face daily, yet we choose not to notice: foreigners are investing in Kenya rather than SA; South African companies are shipping their money abroad as fast as possible. Sweeping amendments to BEE laws are tabled that will accelerate these trends, yet we yawn and pretend it will all come out alright. South Africans are truly sleeping through the revolution, as Malan points out.

Critics of BEE typically point to the handful of politically connected individuals who have been the primary beneficiaries of BEE, leaving the broad mass of South Africans in relative poverty. But there is no doubt the massive expansion of the black middle class (which now outnumbers the white middle class) is a major outcome of these policies. Free Market Foundation economist Loane Sharp argues that the black middle class will double over the next seven years to about 11 million, helping to pull the economy out of the mud.

Far less attention is paid to the costly and disastrous policies and laws that have been passed under the umbrella of BEE. Take Outcomes-Based education, one of the costliest social experiments in the post-apartheid era. The teaching of reading, writing and arithmetic were down-played, and in 2010 The Times reported that five million pupils leaving school were unable to read or write adequately. African drop-out rates at university were 50% according to a 2013 Council on Higher Education report, while just 16% of the 2005 intake completed their three years degrees within the designated time. Pass rates were dropped to make the graduation figures more commodious for the education bureaucrats. All in all, a shockingly poor return for what is one of the biggest expense items in the budget.

This book is not a pleasant read. But to flinch from this touchy subject is fatal, because the technocrats drafting some of the crazy laws that Jeffery dissects have no intention of stopping here. They want to go all the way, wherever that may be. Many of these technocrats are ideologically-driven fellows of the Marxist-Leninist school who harbour a secret admiration for Robert Mugabe. Others are dirigistes who would leave no human endeavour untouched by the supposedly benign hand of government.

Criticising BEE exposes one to charges of racism, if white, or sell-out, if black – which is precisely why so many destructive laws have been allowed to pass in almost total silence.

Most South Africans in the 1990s conceded that it was not enough to simply repeal discriminatory laws, but that remedial action would be needed to overcome the legacy of past discrimination. Hence the Constitution in 1996 was anchored in the concept of non-racialism and equality before the law, with a sub-section authorising the taking of “legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons…disadvantaged by unfair discrimination.”

But elements within the ANC were more committed to the national democratic revolution, which they believe exempted them from the Constitution and the negotiated settlement thrashed out between the ANC, its allies and the National Party. Their goal was eliminating property relations and ensuring demographic representivity in every sphere of society.

Who would have thought South Africans entering university would still have to declare their race, nearly 25 years after the Population Registration Act was abolished? The declared intent of the Employment Equity Act is to end racial prejudice, instead it feeds it by entrenching racial consciousness.

The use of racial quotas was always going to be messy, and so it has turned out. Coloureds in the Western Cape (where they account for nearly half the population) have been over-looked for promotion in the Department of Correctional Services because national demographic quotas require Africans to make up the numbers. In Krugersdorp, the SA Police Services promoted a less qualified African male over an Indian woman with 24 years’ experience, until this was overruled by the Labour court. It is left to the courts to wade through the bizarre calculus of racial quotas and make determinations on who gets the job.

Jeffery provides an interesting expose of “inappropriate appointments” made possible by a provision in the Employment Equity Act allowing the appointment of black people with no proven capacity but “the potential to acquire the ability to do the job.” This soon became the favoured loophole behind which kin, friends, and comrades were favoured over more competent applicants. A 2012 report by the state-funded Human Sciences Research Council warned that “the ANC’s deployment strategy systematically places loyalty ahead of merit and even of competence and is therefore a serious obstacle to an efficient public service.”

BEE is great for the connected elite. Mathews Phosa, former national treasurer of the ANC, until recently sat on more than 80 company boards, Cyril Ramaphosa, deputy president of the ANC, sat on more than 50, though said he planned to resign from many of them to concentrate on his political duties.

There is no quarter of the economy that is not skewed by racial profiling and BEE points, quotas and policies. New procurement regulations have been tightened to stop the “fronting” (or “renting of black faces” as Cosatu calls it), but this raises the costs for businesses, and ultimately consumers. BEE equity deals on the JSE in the decade up to 2008 were valued at about R600 million.

“BEE ownership deals are thus imposing an enormous cost on a country struggling to maintain or expand essential infrastructure…,” says Jeffery.

Land reform has been an admitted failure, with 90% of land reform projects unable to produce a marketable surplus. So government has spent billions of rands in taxpayer money to take hundreds of farms out of production, costing thousands of jobs and billions more in lost revenue.

And so it goes on. This is the ANC’s 20 year scorecard on BEE, as presented by Anthea Jefferey, and it scores an F. It’s time to look past the racial sensitivities and get a real national debate going on this subject before the race engineers annihilate what’s left of the economy.