The UDF calls for a Christmas Against the Emergency. SAHA collection

The UDF calls for a Christmas Against the Emergency. SAHA collection

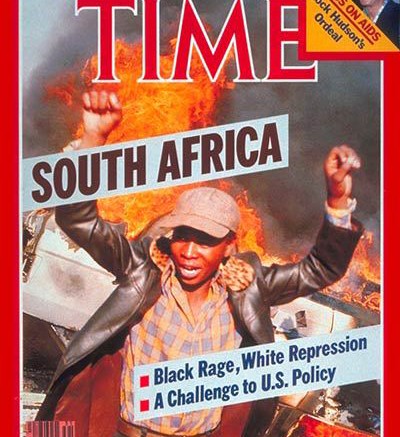

On 28 August 1985 Allan Boesak organised a march in the Western Cape from Athlone Stadium to Pollsmoor Prison. The march was very important, and focused on non-violent resistance to state-repression and detention. Things however did not go as planned as the state tried to stop the march with the use of force, which led to about 28 people dying. This led to increased violence in the Western Cape, reaching a height in September when the police closed about 500 coloured schools and colleges. The UDF and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) called for a two-day strike.In the last months of 1985 the riots spread to Natal as it also became highly politicised. In Natal events followed a slightly different course due to the involvement of Inkatha. There was no call for a consumer boycott, although riots and uprisings did take place. Organisation was led by the Metal and Allied Worker?s Union (MAWU), rather than by the UDF, and resulted in some black on Indian conflict, which went against the UDF?s ideas of non-racialism. Black on black violence also began as UDF and Inkatha members clashed.

By the end of 1985, the UDF still found the township revolts problematic and found itself in a difficult position. It recognised the increased anti-apartheid action in the riots as positive, but was worried about the level of violence and the lack of organisation. The UDF itself was in a state of disarray as many of its leaders were detained, and Congress of South African Students (COSAS) was banned in August. Murphy Morobe mentioned in November that during 1985 8 000 UDF leaders had been detained and that most of the national and regional executives had either disappeared, been killed or left the country. Organisation improved slightly in October when some leaders were released. The UDF was also moving more and more into the role of an organisation, not a front, and was starting to accept more militancy and power in the hands of the people. Some speeches even incited the people to violence, although the UDF was still against the use of violence. At the same time, the UDF was in favour of discussions with the state, especially as the weaknesses of the state were becoming clear, with the collapse of the rand and business leaders holding talks with the ANC in September. A negotiated peace seemed a possibility. By December the UDF was able to provide some direction in resistance and called for another ?black Christmas? consumer boycott. It was however only in 1986 that the UDF became more sure of its position and role.