RAYMOND SUTTNER SOUTH AFRICA

25 JUL 2017 11:27 (SOUTH AFRICA)

There is understandable pleasure that opponents of state capture derive from the revelations in the #Guptaleaks, providing confirmation of various studies and reports and the massive profits that have accrued. Embarrassing as this may be it may be premature to conclude that the Guptas and Zuma are on the way out, especially in the light of the failure of any law enforcement agencies to investigate, as far as is publicly known. There needs to be serious consideration of what can be done to remedy the failure of institutions meant to safeguard constitutionalism. This is urgent in that state capture – being systemic – can persist even if Zuma were to depart. By RAYMOND SUTTNER.

First published on Polity.org.za

Remedying the problems we currently face in South Africa may be more complicated, taxing and difficult than much current debate seems to envisage. That is not to say that removing Zuma, possibly being able to put him on trial, achieving a range of court victories that enhance constitutionalism will be insignificant. Likewise, following the local government setbacks the ANC suffered last year, voting the ANC out of office in 2019 (despite ambiguities in the DA’s stance on questions of inequality) would constitute an important change in our political life.

Equally, the mobilising of thousands of people to march and picket against Gupta appointees to cabinet, and the meetings and protests over the dismissal of those who have sought to defend the fiscus, various calls and demonstrations for the removal of Zuma and return of constitutionalism have been important manifestations of popular anger.

The thousands of people who have met in various gatherings and marched have come from all population groups and sectors of society. They have sometimes represented political and other organisations but often been ordinary citizens who are fed up with what is happening in their country.

It is important to note, however, that this is not an organised force in the sense of people who can easily be called on to act on a regular basis in relation to a clear programme for restoring, rebuilding and enhancing democracy. It is important to note the achievement but also the limitations. This does not represent a body of people united on a long-term basis behind a definite and agreed vision and programme. It can represent a contribution towards that and the energy and the passion that has gone into what has been done can be ingredients for something more, carefully and patiently built over time.

I say “over time” because the urgency and dangerous character of a situation does not mean short cuts can be taken in building an alternative. Such an alternative cannot be provided at the speed we may desire but at the pace required for adequate establishment of what is sustainable, which requires consultation and inputs from all who may form a part of a new political formation. By that I do not necessarily mean a political party, though it could evolve into that but a unity of different people, deriving from different sectors agreeing on basic goals and ways of reaching these or engaged in discussions to achieve such agreement. (Others have articulated some of these sentiments in conferences and other gatherings).

I mention these factors because there may be a need for us to think, rethink, characterise and re-characterise what we are dealing with in South Africa at the moment. This is not to suggest that all other contributions are of no value, indeed I build on many of these. But I think we need to bear in mind some factors that have been insufficiently emphasised.

That the “forces of evil” are encountering a range of embarrassments and have suffered a number of reverses does not mean we are approaching the end of “state capture” (Mondli Makhanya may be implying this in his important article).

When we identify the problems of the present it is important to focus on groupings that influence events outside of formal structures of authority. It is necessary to make three distinctions:

Patronage refers to clientelist relationships where people owe loyalty to a person or powerful people in exchange for rewards like possible jobs or other benefits. The powerful person benefits from the political or other support received and the clients win favours that may be within the power of the patron to offer. It is not necessarily illegal but locates people within a circle of influence that tends to act together for the benefit of one another, albeit to an uneven extent. It need not be restricted to providing jobs or material benefits but tends to also relate to acting in combination politically, developing positions outside of formal structures that may or may not be introduced within and adopted within formal structures at some or other point.

There is patronage entailed in the support for Jacob Zuma but it of course also converges with illegality. There was patronage under Thabo Mbeki in the circles surrounding him and who were appointed and who deferred and sought to anticipate every wish of the “chief”, though there was generally respect for constitutionalism and legality.

In the case of Nelson Mandela patronage was not entirely absent, though it was relatively marginal to the way he won and maintained support, and generally related to his being favourably disposed to people with whom he had worked in the 1950s.

Conventional corruption refers to various forms of illegality performed with the collusion of state officials or political officials in order to secure contracts, positions and that certain actions are performed that will benefit one or other party without following due process.

The Shabir Shaik trial was considered in its time to be a very dramatic case of conventional corruption in his making a series of payments to Zuma in order to secure his political influence in ways that would benefit his businesses. These transactions also led to many of the 783 charges brought against Zuma. These charges were withdrawn in 2009 and have recently been reinstated by the North Gauteng High Court. Zuma and the NPA have taken this on appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal. Despite the huge number of charges against Zuma these were nevertheless a variant of other corruption cases known in South Africa and beyond, involving public officials.

State capture does involve corruption but entails far more and has implications for the sovereignty and the very existence of the state. While conventional corruption relies on the dishonesty of individuals in order to derive a benefit to which s/he is not entitled, state capture derives corrupt benefits through a far more elaborate scheme that aims not for singular, individual benefits but for a long term programme and system, which enables present and future undue, illegal benefits to be derived through determinations made outside of state authority, regulations and the law. State officials may make the actual decisions –in a formal sense- but these are determined in the final analysis by parties outside of state authority.

In other words, state capture which is in place at the moment at the level of the national government, various provinces and to some extent at the local level is an alternative system of practices, which has the effect of displacing or bypassing the formal, legally valid system of governance in favour of illegitimate decision-making deriving from individuals who have no legal authority to make decisions concerning the state. It is also in operation in some of the major State owned enterprises (SOEs). In effect, it has similar effects to that of a military coup replacing an authority, though in this case, it displaces the legal authority –in secret- and acts through it, and thereby undermines state decision-making and sovereignty.

State capture is not adequately covered by the word “corruption” then but relies on determining in many cases who makes decisions, that is, who holds a particular state position of authority, enabling decisions to be made that favour individuals outside the state, in the present case, the Gupta family and their associates. It also provides financial and other benefits to those who provide access to information and decision-making on a legally irregular basis, from the presidency downwards.

The logic of state capture is that it is necessary to know when one needs to intervene, for example, whether to have someone installed in a position or removed from a position or to make a bid for a particular contract or other actions. This is done by accessing data that is not available to other parties who may be bidding for the same contract and thereby being placed in a position to neutralise whatever competing bidders may offer. In order to do this one needs access to information or intelligence. In order to receive this intelligence it is sometimes necessary to obtain confidential information on meetings of SOEs, government departments or the cabinet and individuals who have come under the sway of the Guptas have been willing to break regulations and their oath of office in order to supply this information. Recent reports from the #Guptaleaks reveal that individuals from within the presidency itself are providing such information to the Guptas. This may be without direct involvement of Zuma, but with an assurance that it is done with his agreement.

In consequence of the operation of this system the Public Protector’s State of Capture report, the SACC report, that of a series of leading academics and recent Gupta e-mails have revealed that huge profits-running into billions of rands, have been secured by Gupta-associated companies and individuals. In many cases the processes have contravened South African law.

The products supplied as part of agreements entered into by fair or foul means have sometimes been flawed. Yet in almost all of these cases the Guptas have not been penalised for failing to perform according to what is specified in agreements. This laxity in enforcement appears to be related to the relationships they have formed with people in authority of the entities with whom they have entered agreements.

In the normal course of events a range of investigations would have been opened in order to probe the numerous cases of fraud, money laundering and other illegal and unconstitutional conduct that has come to light and is in the public domain. Although very few people have queried the veracity of the #Guptaemails there has been no announcement of any impending criminal investigation, (as far as has been publicly announced).

The various bodies that might be called on to initiate such investigations have shown themselves to be highly partisan or compromised, in particular the Hawks, Crime Intelligence, State Security, the NPA, SARS and various others.

It is not clear exactly what reward individuals who serve in these institutions receive for their partisanship, though we know that the suspended head of Crime Intelligence, General Richard Mdluli, is alleged to have used safe houses to accommodate friends and other associates, outside of the scope of Crime Intelligence. He seems to have also used his job to warn Zuma of alleged plots on the part of those who could challenge his position as ANC president, ahead of the 2012 ANC conference in Mangaung. It is also possible that individuals heading these institutions have been compromised and they know that Zuma is quite capable of exposing them, if they do not do his bidding. We do not know for sure, but that is the way intelligence officials operate all over the world, and Zuma derives from and presumably continues to operate according to those norms, where required.

Effectively there is no will to act with vigour and even if the courts do order that the 783 charges are reinstated there are further appeals and a long process before a prosecution by the NPA can ensue, probably without much will to succeed. Given that state capture exists and what it entails these charges now seem a relatively less significant question.

Who will be the force to remedy this situation?

I indicated at the outset that remedying these problems is much more complicated than appears from public debate. That the Guptas and Zuma are experiencing serious embarrassment does not seem to have any consequences in terms of criminal investigations.

Assuming that Cyril Ramaphosa wins the ANC presidency, what will he be able to achieve with Jacob Zuma as president until 2019? Will he be able to oust Zuma as State President or is it not possible or even more likely that Zuma will be able to dissolve his cabinet and even dismiss Ramaphosa as State Deputy President? Let us remember that whatever the controversies around Thabo Mbeki, he had a sense of honour and was not prepared to remain State President when he lost the support of the ANC leadership. Even if Zuma loses that support can we assume that he will honour their wishes and resign, should they make the call? We have seen from Zuma’s conduct that when he acts he is indifferent to the effect this has on the currency, the economy or the wellbeing of the country as a whole. This means that we cannot assume that he cares about the consequences of his actions should these be beneficial to him or protects his interests.

Let us fast forward to 2019 where there are –to oversimplify- three potential electoral scenarios: a) a DA-led coalition becomes government or b) an ANC majority is achieved or c) an ANC-led coalition becomes government.

In all of these cases the new government may pledge to end corruption but confronts a state apparatus with loyalties already committed elsewhere, not just to the potentially departed president but even to the Guptas. Even if the Guptas and Zuma fear legal repercussions and flee to Dubai, they could potentially continue their processes of state capture without being physically present. It appears, certainly at a national level and in many provinces and SOEs that there are “systems in place” and people who may be ready to continue the work of state capture.

It is likely at this moment that much intelligence is provided directly to Zuma and bypasses the Minister of State Security David Mahlobo. I remember in the ANC prior to 1994, how Mosiuoa “Terror” Lekota was at one point made head of ANC intelligence. While he held the position intelligence operatives bypassed him and continued to report to Zuma, as they had done prior to 1990. That is a model that can serve, even if Zuma is located in Dubai.

Building a power that will restore and enhance democracy

If conventional organs of representative democracy may be inadequate to rid our country of the scourge of state capture, where do we turn for a remedy? We need to return to “the streets” or places of popular protest, in the light of the resurgence of popular action. We have to return there, not on an episodic basis but with a view to seeing such action as giving impetus to sustainable organisation.

At the risk of inviting cynicism on the part of some I return to the question of the popular –the place of “you and I” the ordinary person in South Africa – in building democracy and in conducting politics. This is not a new idea and is the foundational meaning of the very word democracy. For “the people” to “govern” need not be restricted to periodic voting and in the history of the world and in South Africa there is a tradition of direct popular action. What is needed beyond what we have seen in recent months is a commitment to build this force into a united body of people at first behind limited agreed goals, like clean government, constitutionalism, ending corruption and looting of the state. There is a possibly exaggerated claim that we are already seeing a rebirth of something like the UDF of the 1980s. In fact, the type of unity that needs to be built now ought not to aim at recreating the UDF, which was mainly concerned with the oppressed. What is needed now needs to draw in a range of sectors, some of whom are not from the poorest section of the population but are committed to constitutionalism, clean government and democratic rule.

With the consolidation of organisation there can be debates on a broader programme and vision and how it is realised. Some are impatient or over-optimistic about an imagined impending collapse of the state capture project. We cannot rely on our hopes. We have to build what we want to see. It may take longer than we would like, but we need to learn from what has happened through our being insufficiently vigilant and try, as far as possible to safeguard whatever we may recover. The best safeguard is not in institutions alone, but for the people of the country to be present as much as is practical and possible in future deliberations and political organisation. To create that responsive organisation needs careful building in order to be sustainable. It requires listening and hearing what it is that concerns all who may become a part of rebuilding our democratic future. DM

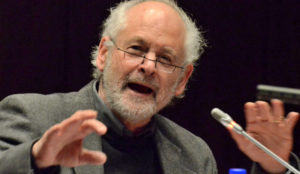

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. Currently he is a Part-time Professor attached to Rhodes University and an Emeritus Professor at UNISA. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His prison memoir Inside Apartheid’s prison has recently been reissued with a new introduction covering his more recent “life outside the ANC by Jacana Media. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner

RAYMOND SUTTNER

SOUTH AFRICA

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-07-25-op-ed-state-capture-and-beyond/?utm_content=bufferd8b2a&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer#.WXfGTdN95E4