Nicholas Woode-Smith 6 June 2017

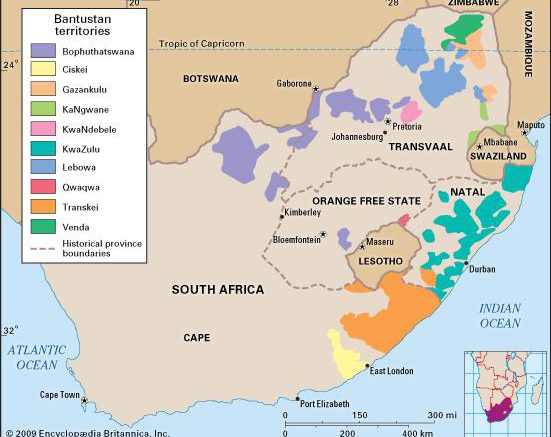

The irony of the conflict over land in South Africa is lost to most of its combatants. While pontiffs fabricate stats on white ownership of land, establishing ‘white monopoly capital’ as a bogeyman, they always tend to ignore that approximately 17 million South Africans still inhabit an artefact of Apartheid – the vestiges of the homeland system – without any meaningful guarantees of land tenure, despite constitutional promises.

While no longer called ‘homelands,’ areas deemed as traditional tribal land is still held by traditional leadership as pseudo-communal land. Officially, the state holds the land in trust. After 2003, traditional leaders gained de facto ownership of the land as they could act in court as if they held ownership.

Why is it that in an effort to destroy all that Apartheid established and represented, post-1994 South Africa still actively defends one of Apartheid’s primary creations?

Apartheid was not just a system of controlling movement, it was a political system that sought to force the secession of racial groups. The creation and enforcement of homelands allowed population groups to be controlled, so as to better work towards Apartheid’s grand social engineering schemes. The impoverishment of many homelands through a myriad of means also guaranteed that a migrant labour force would be at the disposal of the mines and other industries.

So-called ‘traditional’ leaders were just representatives of the Apartheid state. They indirectly ruled their constituents in the National Party’s stead, so as to keep everyone regimented and line their own pockets. The homelands were crucial to this enrichment and power. The Nats were perfectly willing to empower a few individuals to govern the plebs. Indirect rule was common colonial practice, and local rulers loved it. So much so that when the democratic elections threatened the homeland autonomy of Bophutswana, its president actively opposed the notion.

This opposition was not a principled stand for the independence of Bophutswana, which very few people actually supported, but a desperate clinging to a fiefdom. For, like the barons of medieval Europe, the homelands are, even today, fiefdoms.

Under feudalism, peasants don’t own the land. A lord owns the land, called a fiefdom (or fief), and allows people to use it at his whim. But whims are fickle. It is a habit of South Africans to rely on the benevolence of the ruler of the day, but as the Zuma regime hopefully has taught us, we cannot rely on the good nature of those in office. We need a system that guarantees good behaviour and effective governance as best as possible, regardless of the man or woman in charge.

Today, the homelands are still governed by customary leaders, who rule by whims falsely called ‘customary law.’ This is even glorified by some, calling it ‘living customary law’. Families and individuals with some sort of ethnic claim to the homelands are expected to be allowed to inhabit it and work it, but this isn’t profound land ownership. This is serfdom, whereby poor South Africans live by the whims of a ruler, chosen not by mandate but by lineage and arbitrary customary law.

If we are to take our democracy seriously at all, we cannot abide such a regressive and repressive system.

Land reform advocates are partly right about one thing – land is important. What they tend to get wrong is why land is important. Land isn’t some get-rich-quick solution. It is an asset that needs to be utilised properly to allow for capital accumulation. This can only happen if the residents truly own the land they work on. Without ownership of this land, they are merely tenants who are at the whim of traditional leaders.

For all my misgivings with the Democratic Alliance (DA) at least they are fighting for genuine land tenure where it matters. The Free Market Foundation (FMF) have also been leading the charge for meaningful land reform with its Khaya Lam (My Home) Land Reform Project. It is not enough to have a house – what matters is that the people truly own that house as a private entity that they can use as an investment, as an asset, collateral for debt, a place to develop. Without private ownership of land, investment will not happen. The tragedy of the commons strikes, as no one wants to put resources and labour into something they could lose at any moment.

While we live alongside feudalism today, tolerating it because of the lies of cultural entrepreneurs, we also risk entrenching it further. Groups like Black First, Land First (BLF) and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) preach that they want to give land to the people, but their ‘people’ is a vague synonym for ‘the state.’ These Stalinist-wannabes don’t care about the true upliftment of the population. They merely want to attain complete control of all land in South Africa so they can use it to enrich themselves and guarantee their power. Citizens become peasants when they cannot own land.

The virtue of private land ownership summarised

Encourages investment by the owners.

Overcomes the tragedy of the commons, whereby people won’t develop land due to no guarantees that they will benefit.

Can be used as an asset to gain credit, sell for a profit, turn into a business, and other gateways to wealth-making.

Going forward

We can no longer abide ‘culture’ being used as a guise to impoverish the population, or ‘restitution’ as an emotional case to justify totalitarianism. For real and substantive positive change, we need to abolish the South African feudal system.

Communal land is useless land. In fact, the term ‘communal’ is a misnomer, as the real owner is the ruler who can choose at whim who can use what. Even under cases of benevolent leadership, this system of feudalism damages the citizenry.

Without meaningful private ownership of land, there can be no development, and no economic upliftment.

Instead of knee jerk retribution, we should be looking to abolish the last vestiges of Apartheid.

With the homelands abolished, these areas can finally be allowed to prosper. With that prosperity will come employment, capital accumulation, new urbanisation in new cities (which will relax the pressure on our currently-overpopulated city-centres). All this is possible if we stop clinging to a destructive system of sentiment and allow South Africa to enter the 21st century.

Nicholas Woode-Smith

Nicholas is a co-founder and Marketing and Technical Director at the Rational Standard. He is a Council Member of the Institute for Race Relations as well as the Regional Coordinator for African Students For Liberty. Nicholas has written two science fiction novels. He is currently studying Politics, Philosophy and Economics at the University of Cape Town.

https://rationalstandard.com/modern-day-feudalism-south-africa/