-

24 August 2012

The death of dozens of miners in a crackdown on industrial action has exposed deep divisions over workers’ rights in South Africa, 18 years after the end of apartheid.

Nandipha Guniza sat motionless in the front row, wearing a headscarf and clutching her 16 day-old baby boy, Mihle.

Just across the aisle from her, in an enormous marquee set up on the edge of a shanty housing area alongside the Marikana platinum mine, were senior members of the South African government.

The minister of mines was there, along with the minister of police. Nandipha never looked towards them.

After all, this was a memorial service for the 34 striking miners shot dead by police a week earlier, and for 10 others, including two policemen, who died in violent clashes a few days before that. Nandipha’s husband Bonginkosi was one of those killed by the police.

At home in her one-room rented shack, she told me what had happened.

She and her husband had moved here from the Eastern Cape, in the south of the country, because he could find no work there.

At Marikana he was employed as a rock-driller, earning around 5,000 rand ($596, £376) a month.

He joined the strikers who are demanding a tripling of their wages, because he wanted better conditions for his family.

Nandipha told me that she had to pay 500 rand for the little shack, and though there was electricity, water had to be collected from a stand pipe.

And even this was unreliable. If there was heavy rain, the dirt road outside became impassable.

In the yard outside, striking miners all had similar complaints, and several of those earning similar wages to Bonginkosi explained how they had to send money home to pay for support and schooling for their relations or extended families.

They said they supported the breakaway mines union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), which has accused the more established National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) of being too cautious.

It is criticised too, as being too close to the governing African National Congress (ANC) and the new black South African elite, and even to business leaders, including the London-based Lonmin, who own the mine.

Resignation call

For the ANC and for President Jacob Zuma, the killings at Marikana have turned a run-of-the-mill strike-and-wage dispute into a crisis, and the government has responded by announcing a Judicial Commission of Inquiry, looking into the role played by Lonmin, the rival unions, police and government departments.

It is a move that has been welcomed by opposition parties, but the violence here has brought local and world attention not just to the miners’ pay and living conditions, but to what is being seen as a growing gulf separating the government from ordinary people who are asking for more jobs and better services.

After 18 years in power, the ANC faces growing criticism and not just from militant groups.

The man who has achieved the greatest publicity through the Marikana tragedy is of course Julius Malema, the firebrand former leader of the ANC Youth League, now expelled from the party because of his views.

He has demanded that President Zuma, who visited Marikana this week, should resign over the killings, and that all the mines should be nationalised.

When I met him last week, he was at the Marikana police station, with a group of striking miners, laying charges against the police over the killings.

When I asked him about police claims that the miners who were killed had been charging at police lines carrying spears, machetes and possibly guns, he responded by taunting Mr Zuma with jokes about the traditional weapons carried by the president himself at his weddings.

Later, Mr Malema and his supporters disrupted the memorial service in the marquee by taking over the stage, with Mr Malema using the occasion to launch yet another attack on the president, but calling on the striking miners not to turn their backs on the ANC.

“We need to return government to the people,” he said.

‘Just the beginning’

Mr Malema can certainly be accused of opportunistically using the killings to further his own career – and a possible return to the ANC if Mr Zuma was no longer president – but he is not alone in seeing the Marikana tragedy as symptomatic of greater problems in the country.

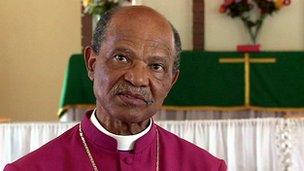

Over the past week, one of the most important figures in the Marikana dispute has been the quietly spoken but forceful Bishop Jo Seoka, president of the South African Council of Churches.

He has driven up from the capital, Pretoria, almost daily, quietly organising meetings between Lonmin management and the striking miners, with whom he clearly has some sympathy.

He also works for a foundation that monitors mine workers’ living conditions, and he told me that housing for some mine workers has not improved since the Apartheid era.

He talked too of greedy politicians and employers, and warned that “the workers have told me this is just the beginning of things to come”.

There could, he told me, be “conflict, with the poor rising up against the rich”.

The killings at Marikana are being seen as a wake-up call for the ANC leadership.

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-19366562