W

ith a characteristic mix of defiance and mirth, Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s president, has chuckled his way through some testing times this year.

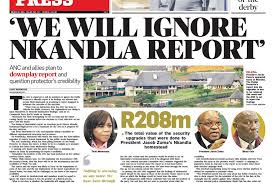

He allowed himself a smile in February as armed police manhandled opposition MPsout of parliament in scenes that shocked the nation. That was after the MPs dared interrupt his annual State of the Nation address with questions about “Nkandlagate,” the scandal in which some $22m of taxpayers’ money was spent on the president’s sprawling private residence in Nkandla.

“People tend to try to find something to talk about Zuma. My surname is very nice and simple,” the president said, responding to an opposition barrage. “Very simple, so they like pronouncing it all the time. So what’s the problem?”

The parliamentary theatrics provide an insight into Mr Zuma’s tumultuous tenure leading Africa’s most advanced economy. It also hints at the character of the steely septuagenarian who shrugged off a raft of controversies to rise to the nation’s highest office.

A recent wave of xenophobic violence, and the election by the main opposition party of its first black leader at the weekend, have put Mr Zuma’s record under fresh scrutiny. For all his robust defiance, in the eyes of his detractors, as well as some ANC members, his presidency has become inextricably linked to scandals, mainly fuelled by a poisonous mix of cronyism, patronage and corruption, that is sullying the image of the government and his party.

The concerns have fed speculation about whether Mr Zuma, who took office in 2009, will serve a full second term, due to end in 2019. At issue is whether he has sullied the image of the government and weakened his party.

Electoral battles

An important test lies ahead for the party at local elections next year, with the ANC expected to face fierce battles to retain majorities in cities such as Johannesburg, Pretoria and Port Elizabeth. The Democratic Alliance, the main opposition, is hoping its election of the party’s first black leader, Mmusi Maimane, this month will boost its chances at the ballot box.

The DA, which already governs Western Cape — the only province not run by the ANC — has struggled to shrug off perceptions that it is a party of white interests. But with Mr Maimane, a polished 34-year-old politician who hails from the Soweto township at its helm, it is hoping to make greater inroads among black voters.

He has vowed to keep up the pressure on Mr Zuma. “We must continue to pursue our legal battles against the powerful and the corrupt,” he said during his victory speech on Sunday. “So President Zuma, if you are watching, please note: we are still coming for you.”

For the ANC, the local election results will set the backdrop for its five yearly congress in 2017, where it will elect leaders and chart its future path. Even if it performs poorly the party will want to avoid a repeat of the bitter leadership battle between Mr Zuma and Thabo Mbeki, the former president, in 2007.

Asked whether Mr Zuma will see out Nkandlagate and other scandals, Ben Turok, a veteran ANC member and former MP, says: “I think the undercurrent of uneasiness is quite strong on this issue and it’s very hard to speculate as to when it will erupt.”

His concern is that “this licence to do misconduct is taking grip” with the danger it escalates and the “wealth of the country is frittered away”.

“The problem we are having is that [in] all these cases . . . it is bad moral judgment, and you cannot afford that in a president,” he says. “People are speaking out and saying that what’s going on is morally indefensible . . . and that causes a national crisis.”

Critics see a link between the patronage and the perceived politicisation blamed for destabilising key state institutions. These include the National Prosecuting Authority, where two senior officials face legal questions over their fitness for office; the Hawks, a unit set up to fight corruption and organised crime, and the respected South African Revenue Service, have been rocked by suspensions and resignations.

“I’ve never interfered with any institutions and will never do so,” Mr Zuma told parliament in March.

But Mcebisi Ndletyana, an analyst at Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection, a think-tank founded by senior ANC officials, predicts Mr Zuma’s legacy will be “10 years lost,” in terms of the damage done to the country’s reputation and the prestige of the party.

Mr Zuma’s rise to the top took place against the backdrop of rampant infighting within the ANC, which forced Mr Mbeki to stand down as president in 2008, and a 2009 recession which cost the country 1m jobs. Zuma supporters had hoped he would heal the wounds within the party, boost employment and tackle poverty. But the factionalism has continued, spilling over into Cosatu, the main trade union federation and key ANC ally, which has been plagued by splits, while the economy has failed to recover with much of the blame placed at Mr Zuma’s door.

Many South Africans fear that the patronage and graft is becoming so pervasive that it is holding back development, particularly in poorer areas suffering from inadequate basic services, such as sanitation, housing and water.

Much of the government-linked corruption involves the award of state contracts, with kickbacks, overpricing and multiple invoicing common complaints that can afflict anything from social housing to the construction of toilets or roads. And while graft flourishes, the ailing economy continues to falter.

The Auditor General’s report for the year ended June 2013 found that of 319 audited entities, including 278 municipalities, just 9 per cent produced a clean bill of health, while R21bn ($1.7bn) was spent in a manner deemed to be unauthorised, irregular and wasteful.

Hierarchy of graft

Yet for the ANC, patronage has become one of the key “bits of glue” holding the former liberation movement together as it means access to wealth and jobs, says David Lewis, the head of Corruption Watch, an anti-graft group.

“Political patronage is really the most dangerous form of corruption,” he says. “A lot of the big tender corruption is this, corruption to keep the ANC together.”

He adds that the high-profile scandals associated with Mr Zuma have come to represent “a brazen abuse of public power” and “real impunity”.

Mr Zuma passionately defends himself against allegations of wrongdoing in relation to Nkandlagate.

For all the noise around the scandals, Mr Zuma is a proven political survivor who still enjoys the public backing of the ANC’s leadership. Indeed, he battled his way to the presidency after being sacked as deputy president in 2005; being acquitted of rape a year later, and having corruption charges against him, related to a multibillion dollar arms deal, dropped just two weeks before the 2009 ANC election victory that swept him to power.

“There are too many people depending on him being where he is to enable him to go quickly or quietly,” says Helen Zille, the former leader of the DA. “What happens in the next election may be relevant but at this stage my judgment is he’s pretty safe.”

The DA is pursuing a lengthy legal process to get a review of the 2009 NPA decision to drop the corruption charges against Mr Zuma. At the heart of its action has been a battle to secure the release of so-called “spy tapes”, which include recordings of conversations between a former head of the Scorpions, an elite investigative agency that was disbanded in 2009, and a former prosecution chief. The conversations were purported to show the timing for charging Mr Zuma was manipulated for political reasons.

The case highlights how allegations that have dogged Mr Zuma for years refuse to disappear — the DA succeeded in having the transcripts released and the legal action is inching forward.

Podcast

Can South Africa’s Obama challenge the ANC?

South Africa’s main opposition party has elected its first black leader. Mmusi Maimane’s good looks and skills as an orator have led some to liken him to Barack Obama. Fiona Symon asks Andrew Engand, FT correspondent in Johannesburg, whether he can challenge the power of the ruling ANC.

Mr Zuma’s dismissal as deputy president in June 2005 came after an adviser, Schabir Shaik, was sentenced to 15 years in jail for soliciting bribes and other payments for Mr Zuma. That month, the NPA announced it was charging him with corruption and fraud, but the case was dismissed in 2006 on technical grounds. He was recharged in 2007.

The saga shone a spotlight on Mr Zuma’s finances. Shaik was accused of paying him R1.2m from his Nkobi Holdings network of companies. But the adviser claimed he merely provided loans to an old comrade.Subsequent legal proceedings painted Mr Zuma as a man who lived far beyond his means. A leaked draft of a 2006 audit said he received R4m between 1995 and 2006 from Mr Shaik and his Nkobi Group.

Bailed out by Mandela

The money was used to pay for such things as the education of Mr Zuma’s dependants, day-to-day housekeeping expenses, bond payments, car rental, cash and medical expenses, it said, adding that Mr Zuma was “cash starved” from at least the end of 1995.

By the end of 2004 the sum of balances of Mr Zuma’s known bank accounts were in overdraft of R421,247, the audit said. The situation was “rectified” by a R1m cheque from Nelson Mandela, the country’s first black president, in 2005.

A former colleague, who was close to him during the anti-apartheid struggle and served in his administration, offers some mitigation, saying a “debt trap” was inadvertently created for ANC fighters, like Mr Zuma, who returned from years in exile with the demise of apartheid having never held salaried jobs and with negligible resources.

“They came back with nothing. And instantly you had to be assimilated. You couldn’t go to a negotiating meeting [wearing] your army fatigues,” he says. “You had to put a suit on. Someone had to buy it, you had to borrow money.”

Mr Turok says it was a phenomenon that “softened our people up and made them vulnerable to all sorts of pressures”. “Some people resisted and others didn’t,” he adds.

Mr Zuma, born into rural KwaZulu-Natal, spent his early years as a herdsboy before joining the ANC at 17. He rose through the ranks to head its intelligence arm in exile earning a reputation for being astute and fearless.

But the former colleague says his “moral compass” tilted in power. “Zuma lost the plot. There are a whole lot of things that have happened that should not have happened,” he says. The hope among many ANC supporters is that the 103-year-old former liberation movement will self-correct.

“In top positions there are people who I would trust with my last farthing,” says Mr Turok. “If they decide the road is clear, without any repercussions, to impose a regime of integrity it can be rolled back,” he adds, citing the strength of the judicial system.

Yet others see a rocky road ahead. “I think the ANC is already stuck,” says Moeletsi Mbeki, businessman and brother of former President Mbeki. “The ANC has no visible agenda besides ‘our turn to eat’ and I think that is one of the difficulties it is faced with.”

| While the country’s ruling elite enjoy the fruits of power, poorer South Africans living in the country’s ubiquitous townships have been displaying their anger with increasing regularity.

Most typically, their frustrations manifest themselves in so-called service delivery protests — demonstrations ostensibly against the poor quality of basic services, which often turn violent. But this year a more shocking phenomenon resurfaced — a wave of attacks against African immigrants left at least seven dead. The xenophobic violence and looting initially erupted in and around the coastal city of Durban in late March, before spreading to Johannesburg and other parts of the country, forcing thousands to flee their homes and causing the government to deploy the army to hotspots last month. Shocked South Africans spoke of their shame at the violence. But there is a general agreement that the attacks can be seen as another expression of the anger felt by ordinary South Africans who complain about the slow pace of economic transformation 21 years after the first post-apartheid election. Foreign shop owners in the townships became the target of people’s ire partly because they were seen to be taking business and jobs away from locals battling with rampant unemployment in one of the world’s most unequal societies. Although the xenophobic attacks seem to have halted there are fears of fresh explosions of anger. “These [protests] are all manifestations of disappointment with the fruits of the elimination of apartheid,” Moeletsi Mbeki, a businessman told the FT. “The dividends of that have clearly gone to the ANC and its middle-class elite. The people left behind — anything could spark their anger.”

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/e6e63754-d964-11e4-8ed9-00144feab7de.html#axzz42dDHBkCz |