When, midway through the American journalist Howard French’s new book, a Zambian politician tells him dejectedly that “we are not a poor people but we have crowned ourselves with poverty,” the phrase resonates with the experience of many countries is modern-day Africa. Resource rich but often misgoverned by autocrats who refuse to leave office – and whose depredations have been bankrolled by Western governments – Africa, despite some bright spots, remains a continent of unrealised hopes and unfulfilled potential. It is that potential, French demonstrates in his new book, that the Chinese have arrived to tap.

When, midway through the American journalist Howard French’s new book, a Zambian politician tells him dejectedly that “we are not a poor people but we have crowned ourselves with poverty,” the phrase resonates with the experience of many countries is modern-day Africa. Resource rich but often misgoverned by autocrats who refuse to leave office – and whose depredations have been bankrolled by Western governments – Africa, despite some bright spots, remains a continent of unrealised hopes and unfulfilled potential. It is that potential, French demonstrates in his new book, that the Chinese have arrived to tap.

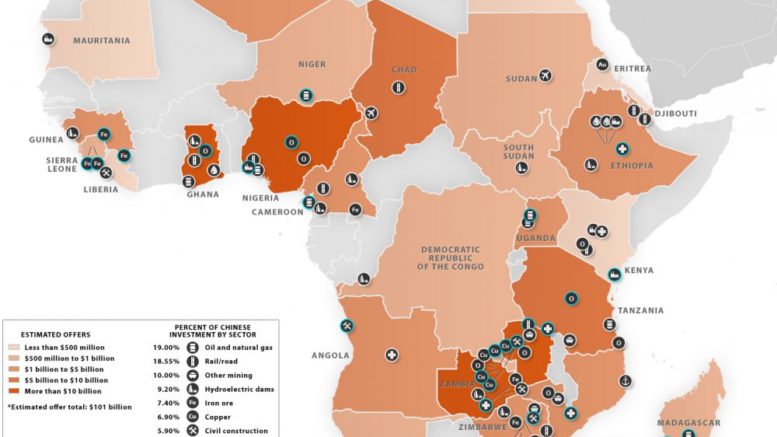

Between 2003 and 2013, China’s investment in Africa grew from $77 million to $2.9 billion, and the ostensible “million migrants” from China (a figure that, after reading the book, seems wildly conservative) arrived in Africa with their government’s blessing to continue their country’s transformation, in French’s words “from being a vessel” of globalization “to becoming an increasingly transformative actor in its own right.”

French, a former New York Times bureau chief in both West Africa and China, brings a nuanced and familiar understanding of both regions to this tale. The book is scrupulously even-handed to its subjects and steers well-clear of anything smacking of jingoism.

The author meets many people, including a foul-mouthed farmer from Henan dreaming of building an empire in Mozambique, a factory owner from the ancient city of Chengdu in Senegal, and a Francophile construction company official in Mali. Almost all appear casually racist about the inhabitants of their new homes in a way that one might have thought had largely disappeared from public discourse (if not private thought).

With a middle class larger than that of India, the African continent is not simply a repository for much-needed natural resources to fuel Chinese economic expansion, but also as a market for the country’s exports. Africa’s population is expected to double over the next 40 years, taking us to just about the time that newly-discovered mineral reserves are expected to run out.

As French writes, “the continent’s rapidly rising population means lots of new mouths to feed, lots more people to be clothed, devices and appliances and goods of all kinds to be sold.”

The Chinese were aided in their quest to expand in Africa by a US government which, during the critical juncture in the early-mid first decade of the millennium, was led by George W. Bush, a man completely uncurious about the world except in the most broad terms, and whose diplomats seemed equally taken by surprise by the rapid expansion that many on the ground had seen coming for some time.

In truth, for nearly a decade before Bush – at least since the Black Hawk Down incident in Somalia during which 18 US servicemen were killed by Somali militias – America had put Africa on the back burner. This has changed somewhat during the presidency of Barack Obama, but not dramatically so.

The picture that French paints of China venturing forth into Africa is not a pretty one, and despite banal slogans of a “win-win” relationship, the Chinese he meets seem surprisingly unaware of how often the ground they have entered has been trod before.

The reader is treated to a vivid account of a short-sighted policy of non-transparent deal-making in Guinea, the rebuffing or insulting of civil society in various countries (generating no small reservoir of ill will) and engagement in the payment of starvation (and often illegally low) wages and non-existent workplace safety.

For the government of China, Africa is just one backdrop among many where new opportunities lie and where much money can be made. But by the end of the book it is hard to argue with French’s conclusion that “here [are] the beginnings of an empire, a haphazard empire, perhaps, but an empire nonetheless”

There are a few unexplored strands of this story that one wishes French had also included. The Chinese presence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of Africa’s most iconic and tragic countries (and one that French knows well, having devoted a large part of his 2005 book to it) goes unexamined. But perhaps this was a conscious decision on the author’s part to highlight some of the rather less-known corners of the continent, such as the aforementioned Zambia, Mozambique and Namibia.

Towards the end of his book, French quotes the historian Peter Duus’ history of Japan’s colonial project in Korea: “[imperialism] requires an available victim – a weaker, less organized or advanced society or state unable to defend itself against outside intrusion.”

Africa, bedeviled as it may be by misrule, today has a more vibrant civil society than at any time in its history. One that robustly confronts the excesses of local governments and also the intrigues of outsiders of many nationalities and political persuasions – all linked by their desire to profit from the continent’s wealth.

Who will prevail in this David versus Goliath battle is unclear, as is whether the democratic gains made in countries like Ghana and Senegal will create the space needed for this side of the debate to succeed. As French clearly recognises, this remains one of the more pressing questions in Africa today.

Michael Deibert is the author of In the Shadow of Saint Death: The Gulf Cartel and the Price of America’s Drug War in Mexico (Lyons Press), The Democratic Republic of Congo: Between Hope and Despair (Zed Books) and Notes from the Last Testament: The Struggle for Haiti (Seven Stories Press).