Not quite what he seemed

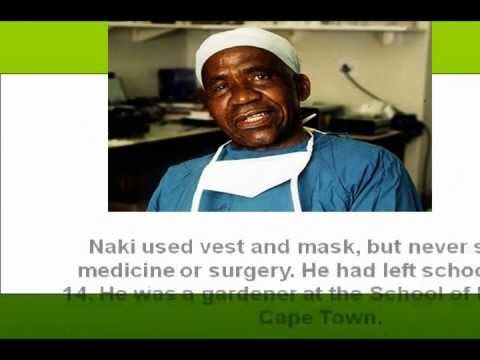

Not quite what he seemedON JUNE 11th this year, The Economistpublished an obituary of Hamilton Naki, a black medical researcher at the University of Cape Town. In that obituary, we described Mr Naki assisting in the first human heart transplant by removing the heart from the donor, Denise Darvall. Our account was drawn directly from Mr Naki’s own words in interviews.

We have since been assured by surgeons at Groote Schuur, the hospital where the transplant was performed, that Mr Naki was nowhere near the operating theatre. As a black, and as a person with no formal medical qualifications, he was not allowed to be. The surgeons who removed the donor’s heart were Marius Barnard, Christiaan Barnard’s brother, and Terry O’Donovan. A source close to Mr Naki once asked him where he was when he first heard about the transplant. He replied that he had heard of it on the radio. Later, he apparently changed his story.

He changed it, it seems, not simply because of the confusion of old age, but because of pressure from those around him. Mr Naki was already a hero, as a man of scant education who had trained himself to carry out extremely difficult transplants on animals. He was also a martyr to apartheid: a man debarred from the proper exercise of his skills, and even from fair pay, by an iniquitous regime. (Christiaan Barnard admitted that, “given the opportunity”, Mr Naki would have been “a better surgeon than me”.) For both reasons, his role was gradually embellished in post-apartheid, black-ruled South Africa. By the end, he himself came to believe it.

The process was assisted by hints from Barnard that Mr Naki had helped him in ways that were not fully known, and by the fact that, under apartheid, any such help on white human subjects would have had to be secret anyway. In the end, a story took shape that looked so plausible to the outside world that not only ourselves, but the Lancet, theBritish Medical Journal and many others accepted it. Yet the same story appeared so ridiculous to the University of Cape Town, staff say, that they did not trouble to deny it.

To report this misapprehension is doubly sad, apart from our own regret at being caught up in it. It is sad that the shadow of apartheid is still so long in South Africa that blacks and whites can tell the same narrative in quite different ways, each suspecting the motives of the other. And it is especially tragic that it should have involved Mr Naki, a man considered “wonderful” by both sides, black and white, and whose life should still be seen as an inspiration.

From the print edition: Middle East and Africa

http://www.economist.com/node/4174683