Although some of the fever has now passed this episode once again displayed a disturbing inability by many of our institutions to remain cool, stand firm and do the right thing under social media mob pressure.

The ongoing discussions about the enduring problem of “racism” in South Africa have also highlighted a basic lack of understanding of the poisonous and insidious forms that racialist agitation can take.

One of the standard methods of racial propaganda – or what the Germans call volksverhetzung – is to focus obsessively on isolated but inexcusable actions by individuals from the targeted group. These are then used to foster a particular stereotype about the group as a whole and create a climate of moral panic whereby violent or arbitrary measures can more easily be taken against members of the group.

The Penny Sparrow controversy is almost a textbook case of how such propaganda works in the age of social media. A bird of little brain posts a vile, racially-insulting comment to a small group on Facebook in reaction to the mess left on beaches by New Year’s Day revellers.

A screenshot of those remarks – equating black South Africans to monkeys – is taken by someone and then rapidly distributed on social media (and then by the media). This is done either recklessly or knowingly, given that the predictable consequence will be to inflame racial tension and hatred. Sparrow’s personal details are found and gleefully circulated online and death threats made against her and her family, and the white minority more generally.

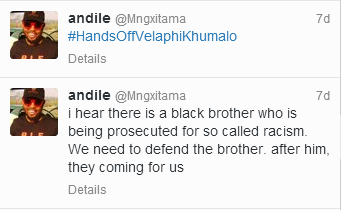

The ANC lays criminal charges against Sparrow and various others but not against Velaphi Khumalo (though others do) – for subsequently saying that whites deserved to be “hacked and killed like Jews” of Nazi-occupied Europe – as he had been provoked.

A completely one-sided debate then ensues in the media on the continued ‘problem’ of white ‘racism.’ Demands are then voiced by politicians and in the media that members of the still relatively advantaged white minority be displaced from their ‘dominant’ position in the economy and dispossessed of their property (and particularly the land). The argument here is that continued white economic dominance implies a superiority that can no longer be countenanced two decades after the end of apartheid.

Finally, in Business Day, Steven Friedman decrees that the “real problem” facing the country is not President Jacob Zuma – or, it could be added, the worst drought in a hundred years, massive unemployment, the great commodities depression or the collapse of a completely ‘transformed’ state into a swamp of corruption, criminality and dysfunction – but rather “the domination of a racial minority and the economic ills that go with that.”

The Chris Hart affair – though running parallel to that the Sparrow one – constitutes a different though not unrelated matter. In the same 24 hours in which Sparrow’s Facebook comments went viral theStandard Bank economist commented, in a long series of tweets, that “More than 25 years after Apartheid ended, the victims are increasing along with a sense of entitlement and hatred towards minorities….”

.png)

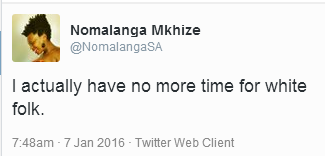

Quite what he meant by the “victims are increasing” is not clear (the actual victims, or those with a sense of victimhood?) But his remarks about the increase in hatred towards minorities caused particular offence to those public intellectuals and politicians who seem to regard it as their life’s work to stoke racial resentment and division. The call went out to “black Twitter” to “roast” Hart and he proceeded to be monstered on social media as a “racist”. (Hart’s academic transcripts from Wits were later leaked to drum.co.za, and then widely circulated online, and he was ridiculed for the failing grades he had received in two of his degree courses.)

The following day the ANC laid criminal charges against him and Standard Bank released a statementwhich claimed that Hart’s comments were “factually incorrect, make inappropriate assumptions about South Africa and have racist undertones” and that he would be suspended and subjected to a disciplinary inquiry. Quite what these “racist undertones” were, or what was factually incorrect about his comments, was not explained.

The answer recently arrived in a letter to staff by Standard Bank Group CEO Sim Tshabalala. In remarks clearly aimed at Hart’s comments on “increasing entitlement”, though not mentioning him by name, Tshabalala stated:

“Racist opinions are usually weapons in a struggle for resources. Some white people, for instance, appear – despite the provisions of our Constitution and our laws – to be tempted to argue that poor black people are not entitled to various goods because they are ‘dirty’ or because they have a ‘victim mentality.’ Some black people seem to think – despite the values and principles stated in our Constitution – that white people are not entitled to be full citizens because they are ‘all racists’. As can be seen from these examples, ‘entitled’ is often a key word in racist thinking.”

This letter was then posted on the Rand Daily Mail website under the heading: “‘Entitled’ is a key word in racist thinking.” This effort to link the word ‘entitled’ with ‘racist’ is somewhat unpersuasive, to say the least. Which white South Africans believe that poor black people are not entitled access to various goods because they are ‘dirty’ or have a ‘victim mentality’? Certainly not Hart. And where has this outrageous view been publicly expressed by any white person of substance over the past decade? Politicsweb reached out to Standard Bank to ask if it could provide one or two examples or illustrations of this apparently widely held view, but was told there would be no additional comment on the letter.

If ordinary white South Africans have an issue it is clearly with the sense of entitlement of President Zuma and the political elite more generally, precisely because it diverts their hard-earned tax money away from the needs of the poor.

Up until the 4th of January 2016 terms such as a “sense of entitlement” or a “culture of entitlement” were a common, accepted, and arguably over-used, part of the political lexicon. The following usages of the term are purely illustrative, as press archive searches through up literally hundreds of similar examples:

“It is important that we rid ourselves of the culture of entitlement which leads to the expectation that the government must promptly deliver whatever it is that we demand.” – Nelson Mandela, February 1995

“The opportunities we provide must be of a kind that builds self-reliance and rewards hard work – anything that encouraged a culture of entitlement would undermine our hard-won freedoms.” –Nelson Mandela November 1997

“The culture of entitlement, so prevalent in our community, has contributed to the ‘name it, claim it’ syndrome where individuals seek an elusive moral justification for engaging in criminal activity.” – Thabo Mbeki November 1998

“Many among us believe that to be poor is to be nobody. We believe that democracy has given us the possibility to prosper. Some believe they are especially entitled to material success because, personally or otherwise, they spent many years in active struggle against apartheid.” – Thabo Mbeki, July 2002

“But with the dominant freebie mentality, all that initiative to better oneself has been destroyed. It has been replaced with a culture of entitlement: The government promised me a house, they must give me a house.” – Khathu Mamaila, August 2006

“Another serious challenge facing the democratic government is the seeping culture of entitlement. As revolutionary agents for change, we should work to wean the people from this debilitating state of mind” – Vusi Mavimbela, September 2009

“We have allowed a culture of entitlement to develop, where people believe that other people owe them something.” Jabu Mabuza, November 2009

The first step is for black youth to squeeze drop by drop out of themselves the victim mentality, sense of entitlement and dependency syndrome that misleads them to believe life owes them something. – Sandile Mamela, July 2015

“Despite the fact that we have provided 3.7 million housing opportunities over the past twenty years, we are still facing a gloomy picture. All this happens against an unfortunate culture of entitlement amongst our people.” – Lindiwe Sisulu, July 2015

“… the various ANC governments of the past 20 years are mostly responsible for any culture of entitlement that South Africans have become addicted to. So the state doesn’t have the moral authority to lecture any lazy or demotivated or entitled citizens.” – Eusebius McKaiser, October 2015

“Entitlement” has thus been an issue of debate and discussion in South Africa for two decades, mostly among black politicians and journalists. It was clearly in this mainstream tradition (not some fringe white supremacist one) that Hart was commenting. It was also hardly unreasonable for him to have taken a view on whether a widely discussed problem was increasing or decreasing.

The truth is that Chris Hart’s offence (Gareth Cliff’s similarly) was not “racism” – according to any common sense definition of the word – but rather racial impertinence. Elements of the dominant group want deference from those they regard as their moral inferiors.

This is why precisely the same statements by white and black South Africans are likely to be met with vastly different responses. The elite’s sensitivities on this score are also immeasurably heightened whenever President Zuma embarrasses them, as he did spectacularly during the Nene affair in December last year.

Any sign of impudence, by a white person, is likely to be met with furious reaction, shouting down and demands for punishment. If the label of ‘racist’ can be successfully pinned on a person (however tenuously) they can then be destroyed.

Even some of the more moderate comments on the recent controversies – arguing that they should not detract from other critical issues – have contained this basic underlying message. Given the misfortunes whites were responsible for pre-1994 white “arrogance” or “ingratitude” today will no longer be tolerated.

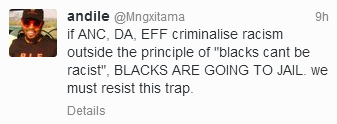

As illustrated by the above while South Africa certainly does have a racialism problem it is not the one our race-conscious intelligentsia is currently obsessing over. Indeed, as some have perceptively observed, a law against racial incitement – of the kind that prevails in Germany and the United Kingdom – would, in the unlikely event that it was fairly and consistently applied, have something of a chilling effect on some of our most fashionably outspoken intellectuals and politicians.

http://www.politicsweb.co.za/news-and-analysis/a-descent-into-racial-madness