Case Studies in Sanctions and Terrorism

Case 62-2

UN v. South Africa (1962-1994: Apartheid; Namibia)

Case 85-1

US, Commonwealth v. South Africa (1985-91: Apartheid)

| Chronology of Key Events | Goals of Sender Country | Response to Target Country |

Attitude of Other Countries | Economic Impact | Assessment | Author’s Summary |

Bibliography |

| 1948 | Nationalist party assumes power in South Africa and, over the next two years passes legislation that forms the pillars of the apartheid system: Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (1949); Group Areas Act (1950), which separates areas of legal residence by race; and the Population Registration Act (1950), which requires official registration by race. (David 215; Massie 21) |

| April 1960 | During a protest against the pass laws, which restrict the movements of blacks and other minorities, sixty-nine blacks are killed by police at Sharpeville. Incident provokes worldwide condemnation of South African regime, calls for UN sanctions. UN Security Council passes Resolution S/4300, with UK, France abstaining, that deplores violence and calls for end of apartheid. (Doxey 1972, 537; Doxey 1980, 61; Massie 63-66) |

| 1961 | African states demand political, economic sanctions against South Africa. South Africa withdraws from British Commonwealth upon becoming a republic, subsequently is excluded from specialized UN agencies. (Doxey 1980, 61; David 217) |

| October 19, 1962 | Francis T. P. Plimpton, US representative to UN, criticizes efficacy, potential use of economic sanctions against South Africa, states US “will continue to oppose” specific sanctions. (David 217) |

| November 6, 1962 | UN General Assembly in a non-binding resolution (1761), calls upon members “separately or collectively, in conformity with the charter” to break diplomatic relations with South Africa, to close ports to South African vessels, to forbid vessels flying their flags to enter South African ports, to boycott South African trade, and to suspend landing rights for South African aircraft. (Doxey 1972, 537; David 217) |

| May – June 1963 | Organization of African Unity is established, recommends economic sanctions against South Africa, termination of diplomatic links, and it calls on US to choose between Africa, colonial powers. (Doxey 1980, 62; David 218) |

| August 2, 1963 | US ambassador to UN, Adlai E. Stevenson, speaking in opposition to mandatory arms embargo: “The application of sanctions in this situation is not likely to bring about the practical result that we seek…. Punitive measures would only provoke intransigence and harden the existing situation…” Nevertheless, US pledges to terminate all new sales of military equipment by end of 1963. (David 218) |

| August 7, 1963 | UN Security Council, with US support, UK, France abstaining, adopts Resolution 181 recommending that member states cease shipment of arms to South Africa. (Doxey 1972, 537; Doxey 1980, 61; David 218-19) |

| December 4, 1963 | UN Security Council, with US, UK, French support, adopts Resolution 182 expanding the arms embargo recommendation to include shipment of equipment, materials for arms manufacture. UK, France state they will distinguish between weapons for internal suppression, external defense. US, UK, France oppose any mandatory or broader economic sanctions. (Doxey 1980, 62; David 219) |

| 1964 | US prohibits direct Eximbank loans to South Africa and places limits on value of loans to US firms exporting there; uses voting power in IMF to block purchase of South African gold. India imposes complete embargo on trade with South Africa. (Chettle 6, 8; Hayes 9; Bissell 78) |

| October 1964 | Newly elected British Labour government bans all arms exports to South Africa. (Doxey 1980, 62) |

| October 21, 1966 | UN General Assembly passes Resolution 2145 by margin of 114 to 2 (3 abstentions) to terminate South African mandate for Namibia, place territory under UN administration. (Doxey 1972, 538; Doxey 1980, 63) |

| June 1968 | At US instigation, IMF refuses to purchase gold from South Africa at prices in excess of $35 per ounce. (de Vries 409-16) |

| January 30, 1970 | UN Security Council Resolution 276 ends South African trusteeship of Namibia. International Court of Justice upholds resolution in 1971, but South Africa ignores ruling. (Doxey 1980, 63) |

| November 1973 | Organization of Arab Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposes oil embargo on South Africa; Iran refuses to comply, becomes South Africa’s major oil supplier. (Doxey 1980, 65, 103-04) |

| 1974 | UN General Assembly votes 91 to 22 to reject South Africa’s credentials; UK, France, US veto Security Council resolution to expel South Africa. (Doxey 1980, 63) |

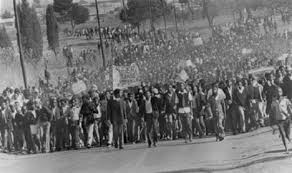

| 1976 | Hundreds of blacks, many of them children, are killed in riots in Soweto township triggered by a protest against inequities in the education system. Event sparks intensified international condemnation of apartheid regime, also raises concerns among foreign investors about stability in South Africa. Some firms that had been reinvesting profits begin to repatriate them. (Doxey 1980, 64; Massie 444) |

| March 1977 | Eleven US multinationals announce adoption of six principles, developed by Rev. Leon Sullivan, first black board member of General Motors, that relate to equal opportunity in workplace. Similar codes are subsequently drafted by EC (September 1977), Canada, some private institutions. (Chettle 65-66; Bissell 85-86) |

| September 1977 | Stephen Biko, leader of the Black Consciousness movement, dies in police custody. To pre-empt protests, government arrests or bans several key opposition leaders. (Massie 421-26) |

| November 4, 1977 | Primarily as result of Soweto riots, subsequent disturbances and repression in South Africa, UN Security Council adopts Resolution 418 declaring arms trade with South Africa (but not apartheid per se) a “threat to peace” under Article 39 and making the arms embargo mandatory (in August, France had announced it would discontinue arms sales to South Africa). (Doxey 1980, 64) |

| December 13, 1977 | UN General Assembly approves recommendation to Security Council for mandatory oil embargo against South Africa; US, UK, France, other key countries abstain, rendering proposal moot. (Spandau 152-53) |

| 1977 | British Commonwealth nations adopt Gleneagles Agreement calling for ban on sports contacts with South Africa. (Hayes 10) |

| February 22, 1978 | Regulations issued by administration of President Jimmy Carter deny export or reexport of any item to South Africa or Namibia if exporter “knows or has reason to know” item will be “sold to or used by or for” military or police in South Africa. (Chettle 17) |

| July 1978 | Rev. Leon Sullivan publishes expanded version of original six principles, announces that 103 companies have committed themselves to apply them. (Bissell 86-88) |

| 1979 | US reduces staffs of US military attaché in Pretoria, South African military attaché in Washington; Congress passes legislation codifying prohibition on Eximbank loans to South African government firms, as well as US firms that do not adhere to Sullivan code. Norway, UK ban sale of North Sea oil to South Africa (David 223-24; Lipton 1988, 16) |

| July 1, 1979 | South Africa Act comes into force in Sweden prohibiting “the formation of any new Swedish companies in South Africa or Namibia. Swedish-owned subsidiaries already operating in those countries are forbidden to make any further investments in fixed assets….” (Swedish Business 24) |

| 1981 | Newly inaugurated administration of President Ronald Reagan announces policy of “constructive engagement” with South Africa; State Department says it “represents above all the reality that there is a limit on the U.S. capacity to use negative pressure to achieve policy results in South Africa.” New policy, formulated by Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester A. Crocker, includes relaxation of diplomatic, economic sanctions imposed under previous administrations, including allowing more South African honorary consuls in US, granting visas to South African rugby team, relaxing controls on nonlethal exports for South African military and police and on restrictions on exports of dual-use military equipment, technology. (Washington Post, 23 July 1986, A14; Baker 8-12) |

| Spring 1981 | Administration of President Ronald Reagan breaks with allies (UK, France, West Germany, Canada) seeking to persuade South Africa to unconditionally implement UN plan for Namibian independence; links South African withdrawal from Namibia to withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola (see Case 86-2 US v. Angola [1986-1992: Cuban troops]). “Washington thereby dismantled collective Western diplomatic pressure on Pretoria and provided the issue of Cuban troops as a rationale for a prolonged South African military presence in Namibia.” (Marcum 161; Massie 487-88) |

| May 1983 | Rev. Sullivan says principles he developed for US corporations operating in South Africa are “beginning to work … but [are] not getting the desired results quickly enough.” He calls on US government to make compliance with Sullivan code mandatory, back it up with sanctions (e.g. tax penalties, loss of government contracts) against recalcitrant firms. (Sullivan) |

| December 6, 1983— January 8, 1984 |

South African forces mount successful campaign into Namibia to destroy logistical base, prevent planned offensive of South-West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). South African forces, however, face sophisticated Soviet-supplied weaponry that raises questions about ability to maintain military superiority in the field. “The lesson of the operation ‘is that they can’t match the Soviet buildup that can occur in front-line states like Angola, and it scares the hell out of them.'” (Washington Post, 24 February 1985, A26; Facts on File 14) |

| September 1984 | South Africa institutes new constitution under which Prime Minister P. W. Botha moves into even more powerful presidency; constitution establishes separate parliamentary chambers for Indian, “colored” representatives while still excluding blacks. New constitution sparks widespread protests, rioting in black townships. (The Economist, 30 March 1985, 27) |

| November 21, 1984 | Three prominent black Americans are arrested in front of South African embassy in Washington, initiating “Free South Africa Movement” in the US. By October 1986, when sanctions legislation is enacted, about 6,000 people have been arrested at embassy, South African consulates around US. (Baker 29; Washington Post, 23 July 1985, A12; 25 July 1985, A1) |

| December 12, 1984 | Of approximately 350 US companies operating in South Africa, 119 agree to expansion of Sullivan principles, committing themselves “to press for broad changes in South African society, including the repeal of all apartheid laws and policies.” (New York Times, 13 December 1984, D1) |

| December 13, 1984 | UN Security Council reaffirms 1977 embargo of arms exports to South Africa, votes unanimously to request that “all states refrain from importing arms ammunition of all types and military vehicles produced in South Africa.” (Washington Post, 14 December 1984, A46) |

| Late December 1984—early January 1985 | Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu, on visit to Washington after accepting Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, criticizes administration’s “constructive engagement” policy, says US could end apartheid “tomorrow” by adopting get-tough policy. (Washington Post, 24 December 1984, C1;International Herald Tribune, 4 January 1985, 1) |

| January 7, 1985 | Coalition of six employer groups, claiming to represent 80 percent of South African workers, issues statement calling for significant changes in apartheid system: meaningful political participation for blacks; recognition of right of all groups to ownership of property, employment; universal citizenship; free, independent unions; equal justice; end to forced removal of people. Statement cautions that such changes can be made only in atmosphere of economic growth, thus opposes sanctions, disinvestment. (Wall Street Journal, 9 January 1985, 31) |

| April 15, 1985 | South Africa announces that it is abolishing Mixed Marriages Act, provisions of Immorality Act prohibiting sexual relations between races. (Washington Post, 17 April 1985, A1) |

| May 7, 1985 | Rev. Sullivan calls for moratorium on expansion by US firms in South Africa and a deadline of two years hence for an end to apartheid. If that goal is not met, he calls for a complete embargo, including withdrawal by US investors there. (Massie 579) |

| Mid-May 1985 | Following imposition of complete trade embargo against Nicaragua, Crocker defends administration’s opposition to sanctions against South Africa by arguing that “South Africa’s economy is 30 times larger than Nicaragua’s and much less vulnerable to the impact of sanctions….” (Washington Post, 15 May 1985, A3) |

| May 21, 1985 | As part of South African effort to destabilize regime in Angola, South African commandos attempt to blow up oil storage tanks in Angola belonging to Gulf Oil Co. but are intercepted by Angolan soldiers. Incident increases support for sanctions in Congress. US Ambassador to South Africa Herman W. Nickel is recalled for consultations. (Washington Post, 10 June 1985, A1) |

| Summer—Fall 1985 | Blacks, who account for over half of all retail sales in South Africa, impose boycott on white-owned businesses in eastern Cape region. Some communities retaliate, while others attempt to negotiate with leaders of boycott. In October, one group of white businessmen sends delegation to Pretoria seeking to improve welfare of blacks in their area. (Washington Post, 27 July 1985, A1; 7 October 1985, A15) |

| July 20, 1985 | In response to ongoing protests, violence in townships, South Africa declares state of emergency in 36 districts. (Massie 584-85) |

| July 24-26, 1985 | France, protesting state of emergency, recalls its ambassador, bans new investment in or loans to South Africa, offers resolution in UN Security Council calling for voluntary sanctions against South Africa, including bans on new investment, imports of krugerrands, new contracts in nuclear energy sector, exports of computers for use by South African army or police. Resolution also calls for immediate lifting of state of emergency, unconditional release of all detainees, freeing of political prisoners, including African National Congress (ANC) leader Nelson Mandela, jailed since 1964. UK, US veto resolution backed by several African nations calling for mandatory sanctions against South Africa, but abstain on French resolution, allowing it to pass. Reagan administration for first time publicly calls on Botha government to lift state of emergency, release detainees, which now number more than 900. At least 16 blacks have been killed by police since state of emergency was declared, 500 since protests began in September. (Washington Post, 25, 26, 27 July 1985, A1; Lipton 1988, 19) |

| July 31, 1985 | House, Senate conferees agree on compromise bill that would impose sanctions similar to those called for in French UN resolution, would also ban all new bank loans to South African government, which most American banks voluntarily suspended seven years before. Legislation would also make observance of Sullivan principles mandatory for US companies with operations in South Africa employing more than 25 people. Citing economic, not political, reasons, Chase Manhattan Bank confirms that it has decided to stop lending to South Africa, will not renew maturing short-term loans, which reportedly total around $400 million. South Africa recalls its ambassador-designate to US, Herbert Beukes, for consultations; bans public funerals for victims of unrest, political statements at any funeral. (Washington Post, New York Times, 1 August 1985, A1; Wall Street Journal, 1 August 1985, 21; Ovenden 128) |

| August 15, 1985 | In speech expected to include announcement of significant new reforms, Botha takes hard line, saying he has “crossed the Rubicon” on road to reform, but that he will set pace, choose terms. Botha rules out significant political power-sharing, blames “barbaric communist agitators” for disturbances in South Africa. Value of rand drops 20 percent following speech. Botha’s speech, in addition to increasing pressure on Reagan administration to take some action, also spurs reassessment of investment policies on part of number of state/local governments, US colleges, pension funds and others. (Baker 32-33; Washington Post, 16 August 1985, A1; 23 September 1985, A22; Ovenden 82-83) |

| August 27, 1985 | Just before he is to lead mass march on prison where Mandela is being held, South Africa arrests Rev. Allan Boesak, founder of United Democratic Front (UDF), largest legal anti-apartheid coalition in South Africa. Concerns about continuing unrest, political instability in South Africa cause foreign banks to reduce lending, refuse to renew maturing short-term loans, causing plunge in value of rand to record low 36 US cents. Of South Africa’s total foreign debt of $17 billion, $11.5 billion will mature within coming year. South Africa closes foreign-exchange, stock markets until 2 September. (Washington Post, 28 August 1985, A1;Financial Times, 28 August 1985, 1) |

| August 28, 1985 | Central Bank Governor Gerhard de Kock leaves for Europe seeking assistance in dealing with financial crisis but finds little sympathy. Black mineworkers union announces that it will strike at seven gold mines beginning 1 September. (New York Times, Washington Post, 29 August 1985, A1;Washington Post, 30 August 1985, A1) |

| August 29, 1985 | South Africa’s four main business groups call on government to open negotiations with black leaders, asserting that any measures adopted to deal with economic crisis must include political changes to be effective. (Financial Times, 30 August 1985, 1) |

| September 1, 1985 | South Africa announces temporary “standstill” on repayments of commercial debt principal, including short-term interbank loans, sets up two-tiered exchange system for rand to discourage disinvestment. Finance Minister Barend du Plessis says South Africa will continue to service its debts; total interest on foreign loans is estimated to be no more than 6 percent of annual export earnings; hence meeting interest payments is not expected to pose problems. (Washington Post, 3 September 1985, A1; 4 September 1985, A26; Financial Times, 2 September 1985, 1, 16; 3 September 1985, 1; 4 September 1985, 1) |

| September 5, 1985 | Responding to debt repayment moratorium, uncertainty over how it will be resolved, American banks refuse to extend short-term credits for US exports to South Africa. (Washington Post, 6 September 1985, A29) |

| September 9, 1985 | Reagan imposes limited economic sanctions by executive order in effort to head off embarrassing defeat in Congress, where House-approved compromise legislation has been stalled in Senate by Jesse Helms (R-NC) filibuster. Executive order bans exports of US-manufactured computer hardware, software to agencies that administer or enforce apartheid; exports of nuclear goods, technology; loans to South African government, except for educational, housing, or health facilities open to all races. Order also mandates compliance with Sullivan principles as called for in congressional legislation. Unlike congressional measure, order does not immediately ban importation of krugerrands, instead calling for discussions of possible legal problems of krugerrand ban under General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), nor does it mandate additional sanctions if “significant progress” toward ending apartheid is not made in 12 months. Reacting to Reagan’s imposition of limited sanctions Archbishop Desmond Tutu states: “I think I should say now [Reagan] is a racist pure and simple…. Get rid of constructive engagement, apply to South Africa the policies you apply to Nicaragua, and voila, apartheid will end.” (Washington Post, 10 September 1985, A1) |

| September 10, 1985 | Eleven of 12 EC nations agree on package of limited sanctions, including tighter enforcement of arms embargo, ban on all nuclear, military cooperation with South Africa; UK withholds approval pending assessment of sanctions’ impact. UK also objects to recall of military attachés, “discouraging” of cultural, scientific exchanges. In Basel, Switzerland, central bankers meeting at Bank for International Settlements reportedly refuse to consider request from de Kock to put together official “rescue” package for South Africa. (Washington Post, 11 September 1985, A1, A20) |

| September 25, 1985 | UK agrees to adopt measures previously approved by other EC ministers, withdraws its defense attachés from British embassy in South Africa. (Washington Post, 26 September 1985, A33) |

| October 1, 1985 | Following consultations with major trading partners, none of whom object, Reagan imposes ban on import of krugerrands, effective 11 October. (Washington Post, 3 October 1985, A27) |

| October 20, 1985 | Commonwealth of Nations overcomes UK objections, adopts sanctions package similar to that adopted by US, EC. Commonwealth package also includes ban on government loans to South African government, threatens increased sanctions if progress on dismantling apartheid is not made within six months. Package falls short of Commonwealth’s Third World members’ call for immediate comprehensive, mandatory sanctions. (Washington Post, 21 October 1985, A16; 22 October 1985, A22; Lipton 1988, 16) |

| November 2, 1985 | South Africa bans all television, radio, photographic news coverage of unrest in designated emergency areas, restricts movements of print reporters. (Washington Post, 3 November 1985, A1) |

| November 18, 1985 | One hundred eighty-six American companies operating in South Africa, all signatories of Sullivan principles, send telex to Botha urging him to do something to “lower tensions” in black school system. “It is the first time any group of foreign companies has intervened so directly with the government on a domestic political issue.” (Washington Post, 19 November 1985, A1) |

| November 27, 1985 | Financial Times reports that Central Bank Governor de Kock recognizes the need for evidence of political reform in order to complete the debt rescheduling and that he “hinted that this message had finally reached the Government after direct warnings from Dr. Fritz Leutwiler.” (quoted in Harris 802). |

| December 10, 1985 | Unable to reach mutually acceptable agreement with its creditors, South Africa announces that it is extending freeze on debt repayments until March 31, 1986. After an earlier meeting with creditors, Central Bank Governor de Kock had complained that politics was interfering with negotiations because “The banks can’t be seen as helping South Africa because it would be seen as propping up apartheid.” (Washington Post, 11 December 1985, A32; Massie 595) |

| January 31, 1986 | “[A]pparently as a gesture in the direction of the political reforms that the banks had indicated were a precondition for settlement,” Botha gives speech announcing that influx controls would end and pass laws controlling movement of blacks into “white” areas would be repealed 1 July. (Ovenden 89) |

| February 1986 | Fritz Leutwiler, Swiss banker mediating between South Africa and foreign banks holding South Africa’s debt, meets with representatives of banks whose loans are caught in standstill “net”; they agree to interim settlement, until 30 June 1987, that includes “an increase of 1 percent in the interest payable, an immediate principal repayment of 5 percent on those debts originally maturing before the end of March 1986, a 5 percent principal repayment on the original maturity date of all other debt caught in the ‘net’.” (Ovenden 89) |

| March 4, 1986 | Botha lifts state of emergency. (Washington Post, 13 June 1986, A26) |

| May 19, 1986 | South African commandos strike alleged ANC “operational centers” in Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia. Botha attempts to justify attacks as legitimate response to terrorism, similar to recent US air raid on Libya. Reagan administration lodges formal protest, recalls its military attaché from Pretoria, expels South Africa’s military representative, but refuses to impose additional economic sanctions. (Washington Post, 20 May 1986, A1, A23; 21 May 1986, A1; Baker 42) |

| June 12, 1986 | To head off planned protests marking 10th anniversary of Soweto uprising, South Africa declares nationwide state of emergency. More than 1,000 persons are detained on first day of decree. Simultaneously, Eminent Persons Group, appointed by Commonwealth to mediate between South African government and ANC, reports that it has failed, claims that Botha “is not interested in negotiations at this point in time”, calls on Western nations to impose widespread sanctions. (New York Times, 13 June 1986, A1, A12; Massie 604-06) |

| June 16, 1986 | In commencement address adapted for New York Times, Archbishop Tutu calls for international economic sanctions: “There is no guarantee that sanctions will topple apartheid, but it is the last nonviolent option left, and it is a risk with a chance. President Reagan’s policy of constructive engagement … [has] failed dismally.” (New York Times, 16 June 1986, A19; Financial Times, 16 June 1986) |

| June 18, 1986 | By voice vote, House approves, sends to Senate legislation imposing trade embargo against South Africa, requiring all US companies with operations there to disinvest within 180 days. US, UK veto UN Security Council resolution that would impose limited sanctions against South Africa. World Council of Churches reports that nearly 3,000 persons have been detained in week since state of emergency was declared. (New York Times, 19 June 1986, A1) |

| June 29, 1986 | Zulu Chief Gatsha Buthelezi denounces House sanctions bill, asserting blacks “want more jobs, not less jobs. They want more investment, not less investment.” (Washington Post, 30 June 1986, A17) |

| July 22, 1986 | In his first major speech devoted to South Africa, Reagan urges Congress, Western Europe to “resist this emotional clamor for punitive sanctions,” criticizes state of emergency, but praises Botha regime for “dramatic change” in recent years and attacks ANC for using “terrorist tactics.” Moderate Senate Republicans criticize speech for offering no new initiatives, indicate their support for limited additional sanctions. (Washington Post, 23 July 1986, A1; 28 July 1986, A17; Baker 44; Massie 614-16) |

| August 4, 1986 | Seven representatives of Commonwealth nations, meeting at “mini-summit” in London, split over sanctions against South Africa, with Thatcher agreeing only to call for voluntary bans on new investment, promotion of tourism in South Africa. She also pledges not to block possible EC sanctions to be considered next month. Other six representatives agree to recommend additional immediate measures, including banning new bank loans to private as well as public borrowers, imports of agricultural goods, uranium, coal, iron and steel, air links. Proposed measures would also define reinvestment of retained earnings as new investment, thus bringing it under ban. (Wall Street Journal, 5 August 1986, 1; 6 August 1986, 21; Washington Post,New York Times, 5 August 1986, A1; Commonwealth Secretariat, app. 3, 3) |

| August 15, 1986 | Sanctions bill sponsored by Richard Lugar (R-IN) passes Senate 84-14. (Massie 617) |

| September 4, 1986 | In attempt to head off sanctions legislation, Reagan renews executive order authorizing limited sanctions for another year. A week later, House of Representatives approves more moderate Senate bill without amendment and sends it to president. (Baker 44-45; Massie 617-18) |

| September 16, 1986 | EC votes to ban imports of iron, steel, gold coins, and new investment in South Africa; investment ban does not extend to reinvestment of retained earnings. Ban on coal imports, most significant of proposed sanctions, is blocked by West German, Portuguese opposition. (Washington Post, 17 September 1986, A1; Lipton 1988, 29) |

| September 17, 1986 | Coca-Cola Co., one of largest, most visible US companies remaining in South Africa, announces it will sell its operations there to multiracial group of investors as “statement of our opposition to apartheid.” Company executives deny move was motivated by planned boycott of its products announced a week earlier by Southern Christian Leadership Conference. (Washington Post, 18 September 1986, A1) |

| September 19, 1986 | Following EC’s lead, Japan bans imports of iron and steel, but not iron ore or coal. (Washington Post, 20 September 1986, A16) |

| September 26, 1986 | Reagan vetoes sanctions bill. California Governor George Deukmejian signs legislation requiring state to divest $11 billion in South African-related investments. (New York Times, 27 September 1986, A1) |

| October 2, 1986 | Senate overrides Reagan’s veto of sanctions bill by vote of 78 to 21, following House vote to override earlier in week (313 to 83). Falling well short of House-proposed sanctions, Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act (CAAA) extends and expands existing sanctions: it bans all loans to, new investment in South Africa (ban does not extend to letters of credit, loan rescheduling, reinvestment of retained profits); bans imports of iron and steel, coal, uranium, textiles, agricultural products, goods produced by government-controlled firms (parastatals), except for strategic materials for the US military; transfers South Africa’s sugar quota to Philippines; bans export of petroleum and products, weapons and munitions; severs air links; prohibits US banks from accepting South African government deposits (worth $329 million in March); prohibits government agencies from cooperating with South African military, promoting trade or tourism in South Africa. In addition, Act authorizes $40 million in aid for disadvantaged South Africans, $4 million a year in scholarship funds for victims of apartheid; calls on ANC to suspend “terrorist activities”; threatens to impose additional sanctions if “substantial progress” toward dismantling apartheid is not made within a year of enactment. Act also restricts US military assistance to countries that do not join UN arms embargo, provides for sanctions against countries that “benefit from or take commercial advantage of” limitations imposed on US business. CAAA also sets five conditions for lifting of sanctions (see “Goals of Sender Country”). (Washington Post, 3 October 1986, A1, A16; New York Times, 3 October 1986, A1; Hayes 2; Baker 44-45, app. D; Lipton 1988, 18, app. 6) |

| Fall 1986 | “Flood” of companies announce withdrawal from South Africa (see “Observed Economic Statistics”). Anti-apartheid activists, however, criticize licensing, other arrangements that allow parent companies to continue selling, servicing their products in South Africa. Barclays Bank, until recently largest British investor in South Africa, becomes first British firm to pull out, announcing that it will sell its 40 percent share in South Africa’s second largest commercial bank, worth estimated $250 million. Student groups have been pressuring Barclays to withdraw; its share of student loan market has fallen to 17 percent from 28 percent in 1981. Barclays sells its interest for only $8.10 a share, far below market price of $14.58. (Washington Post, New York Times, 22 October 1986, A1; Wall Street Journal, 22 October 1986, 3; 24 October 1986, 2; Washington Post, 25 November 1986, A1, A17; The Economist, 29 November 1986, 65;Business Week, 8 December 1986, 54) |

| November 1986 | UN arms embargo is significantly tightened by addition of spare parts, components, broadening of definition of covered articles to include military, police vehicles, equipment. (Lipton 1988, 15) |

| December 9, 1986 | Rev. Sullivan announces that he will mount major divestment campaign, call for total economic embargo in June if significant progress in South Africa is not made by then. Sullivan says he has already received pledges of cooperation from pension funds, university and other investment funds with more than $60 billion in assets. (Washington Post, 10 December 1986, G1) |

| January 1987 | Five major anti-apartheid groups issue guidelines for local governments with divestment laws on how to tighten them so as to prohibit types of licensing, franchise agreements signed by most US companies when pulling out of South Africa. Groups identify Kodak, which, when it withdrew in November, also prohibited its branches worldwide from selling its products to South Africa, as only company thus far to meet their criteria for severing all ties when disinvesting. Reagan administration grants exception to sanctions for South African uranium imported for reprocessing on behalf of third countries (e.g., Japan). (Washington Post, 20 November 1986, A1; New York Times, 9 February 1987, D1; Lipton 1988, 53, 65) |

|

February 20, 1987 |

US, UK, West Germany veto Security Council resolution calling for package of mandatory sanctions modeled on those imposed by US over Reagan’s veto in fall of 1986; France, Japan abstain. (Hayes 1) |

| March 24, 1987 | With interim agreement due to expire in June, South Africa reaches three-year agreement with foreign creditor banks on rescheduling its debt. Under agreement, South Africa will continue to service all its debt, will continue to make principal payments on official debt (which was never frozen) as originally scheduled, and, by June 1990, will repay 13 percent of total principal of debt in standstill net. Agreement also contains two “exit” options, one that allows banks to convert “short-term claims frozen inside the net into repayable long-term debt,” another that allows creditors to use claims to purchase equities in South Africa. News of agreement is interpreted in South Africa as indicating “a major shift in the perceptions and attitudes towards South Africa of some of the world’s biggest and most influential banks” and as “taking the sting out of the most damaging sanction yet.” (Financial Times, 25 March 1987, 1; Ovenden 91-93) |

| June 3, 1987 | Rev. Sullivan calls on 127 US companies that are signatories to his code to pull out of South Africa, urges Congress to penalize other countries replacing US business, urges administration to break diplomatic relations, impose complete economic embargo against South Africa until it ends apartheid. (Washington Post, 4 June 1987, E1) |

| August 9, 1987 | National Union of Mineworkers begins three-week strike, longest legal strike in South African history. (Baker 94) |

| October 1987 | In report to Congress required by CAAA, Reagan says that sanctions have not contributed to achieving Act’s goals, that he will not recommend additional sanctions. (Ovenden xiv; Baker 84) |

| December 1987 | Congressman Charles B. Rangel (D-NY) successfully adds amendment to FY 1988 Deficit Reduction Finance Bill that denies foreign tax credits to US firms operating in South Africa. (Ovenden 51; Baker 62) |

| February—March 1988 | South Africa “bans” all major nonwhite opposition groups, prohibits political activity by trade unions. Variety of new sanctions bills are introduced in Congress. (Washington Post, 23 March 1988, A1; International Trade Reporter, 30 March 1988, 473) |

| May 1988 | US importers of strategic minerals increase purchases, stockpile to guard against possible retaliatory actions by South Africa if Congress passes tough sanctions bill. South Africa continues to reject retaliatory export embargoes, saying that it is opposed to sanctions, boycotts in principle. (Washington Post, 6 May 1988, A1) |

| August 11, 1988 | By vote of 244 to 132, House approves sanctions legislation that would end all trade with South Africa except for imports of strategic minerals; require complete disinvestment; end military and intelligence cooperation; deny federal oil, gas, coal leases to international oil companies with investments in South Africa (primarily Royal Dutch-Shell, British Petroleum); prohibit US-owned or -registered ships from transporting oil to South Africa; require retaliation against other countries undercutting US sanctions. Legislation does not come to vote in Senate, dies at end of session. (Washington Post, 12 August 1988, A1) |

| December 1988 | Peace pact is signed in New York in which South Africa agrees to implement UN plan for Namibia’s independence in return for withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola. (Washington Post, 21 March 1990, A1) |

| January 11, 1989 | Rev. Boesak credits sanctions with role in inducing South Africa to sign UN accord providing for withdrawal of Cuban troops in Angola, independence for Namibia. In calling for additional sanctions, Boesak says, “The pressure of sanctions forced them [South African government] to the negotiating table. If that is true for Namibia and Angola, it must also be true for South Africa.” (Washington Post, 12 January 1989, A30) |

| April 26, 1989 | Mobil, largest remaining American employer in South Africa, cites Rangel amendment, which may have cost it $5 million in 1988, as one reason for its planned withdrawal from South Africa. Mobil reportedly will sell its assets there for around $155 million, recording a net book loss of about $140 million on the sale. In June, Goodyear also cites Rangel as one factor in its decision to withdraw. (New York Times, 27 April 1989, D1; 29 April 1989, A1; Wall Street Journal, 27 April 1989, A3) |

| May 17-18, 1989 | Newly elected President George Bush adopts more conciliatory attitude toward ANC, other black opponents to Botha regime. He meets with Rev. Boesak and Archbishop Tutu who urge the Bush administration to impose financial sanctions on South Africa. Bush also announces he has invited Albertina Sisulu, wife of imprisoned ANC leader Walter Sisulu and co-presidents of banned UDF, for a visit in June. (Washington Post, 18 May 1989, A17; 19 May 1989, A13; 19 July 1989, A16; Financial Times, 20 June 1989, 20) |

| Late May 1989 | Central Bank Governor de Kock warns that economic stagnation threatens country if political reforms are not taken to restore confidence, head off additional sanctions and induce lifting of existing ones. (Washington Post, 2 June 1989, A28; New York Times, 4 June 1989, section 4, 2) |

| June 1, 1989 | Tutu, three other prominent church leaders urge international banks to exert financial pressure on South Africa to dismantle apartheid by refusing to reschedule its debts, refusing to extend trade credits. (Washington Post, 2 June 1989, A28) |

| July 1989 | Mandela, still prisoner, meets with Botha in president’s office in Cape Town. US General Accounting Office (GAO) releases report noting that failure to identify products associated with parastatals has inhibited enforcement of ban on imports from South African government agencies, state-owned companies identified by State Department. In particular, US Customs Service was generally unaware that gold bullion should fall under parastatal ban because mining companies sell gold to South Africa Reserve Bank, which then markets it internationally. Although US imports of gold bullion from South Africa fell to zero in 1987-88 from their 1986 level of $79 million, US imports of gold bullion from UK, Switzerland between January 1987, March 1989, were $175 million, $164 million, respectively. (Washington Post, 13 July 1989, A1; GAO 3) |

| August 8, 1989 | Commonwealth foreign ministers meeting in Canberra, Australia, propose package of financial sanctions to be considered by Commonwealth heads of government at meeting in October. Measures recommended include official lobbying of banks to impose tough conditions on South Africa when its debt is rescheduled next year; tightened restrictions on new lending to South Africa; imposition of tougher terms for trade financing. New restrictions, however, are blocked by Britain at the October meeting of heads of state. (Financial Times, 9 August 1989, 1; 23 October 1989, 2) |

| August 14, 1989 | Botha, who suffered mild stroke in January, resigns abruptly. In his resignation speech, he takes hard line against ANC, harshly criticizes expected successor de Klerk. (Washington Post, 15 August 1989, A12) |

| August— September 1989 |

Congress considers defining CAAA ban on new loans to include rescheduling of old ones. Treasury officials testify against such changes, arguing that they would encourage South Africa to default, which would help government rather than anti-apartheid cause. British anti-apartheid coalition launches campaign to pressure three British banks not to reschedule South Africa’s debt; group also calls for tighter enforcement of existing oil, arms embargoes, as well as additional trade, financial sanctions. (International Trade Reporter, 9 August 1989, 1049; Financial Times, 2 September 1989, 3) |

| September 5-6, 1989 | Black opposition groups call for general strike to protest exclusion from elections. Acting President de Klerk, campaigning on platform of reform, negotiations, is elected to five-year term; his National Party wins majority in parliament, although by slimmest margin since party was founded. Seats are lost nearly equally to newly formed liberal Democratic Party, Conservative Party; de Klerk interprets results as mandate for reform. (Financial Times, 8 September 1989, 6) |

| September 13, 1989 | Largest legal protest march since 1959, involving over 20,000 people, takes place peacefully in Cape Town. (Washington Post, 14 September 1989, A1) |

| October 2-3, 1989 | President Bush sends annual CAAA report to Congress in which he concludes that sanctions “have not to date been successful,” declines to impose additional measures. Testifying on report, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Herman J. Cohen is a bit more optimistic, saying that “sanctions have played a role in stimulating new thinking within the white power structure of South Africa.” Cohen says administration would like to see some normalization of political life in South Africa, such as releasing political prisoners, unbanning political organizations, by end of year; he adds that administration would consider imposing additional sanctions if actions toward ending apartheid are not taken in next parliamentary session, to be held from February to June 1990. (Washington Post, 4 October 1989, A8) |

| October 10, 1989 | De Klerk announces Walter Sisulu, six colleagues will be released from prison within days; phones Margaret Thatcher directly to inform her. Move is “clearly [timed] in order to strengthen the anti-sanctions posture of … Thatcher” in advance of Commonwealth heads of state meeting beginning 11 October. (Financial Times, 12 October 1989, 15; Washington Post, 16 October 1989, A1) |

| October 18, 1989 | Preempting anti-apartheid activists’ efforts to increase financial pressure, South Africa concludes three-and-a-half-year rescheduling agreement with its creditors several months before current agreement is due to expire. Anti-apartheid groups criticize banks for easing the immediate debt pressure on South Africa. However, with continued capital outflows South Africa will probably be able to grow no more than 2 percent a year rather than at rate of 3 percent to 4 percent. (Washington Post, 19 October 1989, A45; 20 October 1989, A37; Financial Times, 20 October 1989, 4, 18) |

| October 22, 1989 | Commonwealth summit ends with joint communiqué agreeing to maintain existing sanctions, threatening to impose additional measures if progress in dismantling apartheid is not made in six months. However, Thatcher undercuts joint statement by issuing her own that is critical of sanctions, calls for “positive and constructive steps” rather than “tightening [of] sanctions and the imposition of new punitive measures….” (Financial Times, 23 October 1989, 2; Washington Post, 25 October 1989, A38) |

| November 16, 1989 | De Klerk orders immediate opening of whites-only beaches to blacks, announces his intention to repeal Separate Amenities Act, which enforces system of “petty” apartheid measures (much of which has already eroded), as soon as possible after parliament convenes in February. (Washington Post, 17 November 1989, A1) |

| January 24, 1990 | Assistant Secretary of State Cohen meets with de Klerk, tells him that, if conditions set out in CAAA are met, “the administration will immediately consult with Congress with a view toward suspending or modifying sanctions.” (Washington Post, 25 January 1990, A29) |

| February 2, 1990 | In speech opening parliament, de Klerk promises to release Mandela as soon as possible; suspends death penalty; unbans ANC, Pan Africanist Congress, South African Communist Party, 33 other opposition organizations; releases some political prisoners, although not those imprisoned for violent offenses (Human Rights Commission in South Africa estimates that only one-fourth of 2,500 convicted political prisoners serving sentences will be eligible for release); repeals parts of Emergency Regulations, but does not lift state of emergency completely; lifts all restriction orders on individuals; limits duration of detentions under Emergency Regulations. (Washington Post, New York Times, 3 February 1990, A1) |

| February 11, 1990 | Mandela is released without conditions, asks international community to keep pressure on South Africa: “To lift sanctions now would be to run the risk of aborting the process toward ending apartheid.” Bush telephones Mandela, invites him to visit White House. Bush says he spoke two days earlier with de Klerk, invited him to visit as well. (New York Times, 12 February 1990, A1, A17;Washington Post, 12 February 1990, A1) |

| February 12, 1990 | Thatcher calls for meeting of EC foreign ministers to consider community-wide lifting of voluntary sanctions. Bush says US sanctions cannot be lifted until South Africa has met conditions outlined in CAAA. (Financial Times, 13 February 1990, 1; New York Times, 13 February 1990, A17) |

| February 15, 1990 | Twenty thousand whites march through Pretoria in protest against de Klerk’s release of Mandela, legalization of ANC. (Washington Post, 16 February 1990, A25) |

| February 20, 1990 | Thatcher unilaterally lifts ban on new investment in South Africa after 11 other EC foreign ministers decide only to “re-engag[e] South Africa in cultural and scientific cooperation.” (Financial Times, 21 February 1990, 1) |

| March 22, 1990 | Secretary of State James A. Baker III meets with de Klerk in Cape Town, in highest-level meeting between the two countries in more than a decade. Mandela, other black leaders criticize meeting as premature. (Washington Post, 23 March 1990, A15) |

| April 17, 1990 | De Klerk rejects majority rule as “unacceptable” to whites: “We believe that majority rule is not suitable for a country like South Africa because it will lead to the domination and even the suppression of minorities.” (Washington Post, 18 April 1990, A1) |

| April 19, 1990 | In speech to parliament, de Klerk announces that, while government will repeal Separate Amenities Act, it will delay for at least a year consideration of main “pillars” of apartheid: Group Areas Act, Land Acts, Population Registration Act. He also noted that those laws may not be fully repealed, but may be replaced with substitute legislation. (Washington Post, 20 April 1990, A20) |

| May 2, 1990 | South African government, ANC hold first formal talks, focusing on remaining obstacles to substantive negotiations on political reform, including release of all political prisoners, lifting of state of emergency, general amnesty for all political exiles, end to ANC’s armed struggle. (Washington Post, 3 May 1990, A1) |

| May 8, 1990 | De Klerk begins 16-day trip to EC. Netherlands says it would welcome de Klerk visit later in year, Portugal pledges to support lifting of sanctions at upcoming meeting of EC foreign ministers. Other EC leaders praise de Klerk’s reforms but refuse to discuss lifting of sanctions. (Financial Times, 9 May 1990, 6; 16 May 1990, 24) |

| June 4, 1990 | Mandela begins 6-week, 13-nation tour, including several days in US, during which he says sanctions will be “uppermost in all the discussions.” (Washington Post, 5 June 1990, A20) |

| June 7, 1990 | De Klerk announces that state of emergency will not be renewed when it expires 8 June, except in Natal, where interfactional violence between ANC, Zulu Chief Buthelezi’s Inkatha organization has killed 3,500 people in last three years. De Klerk also says 48 blacks detained under state of emergency will be released as gesture of goodwill; however, between 350 and 3,500 political prisoners remain in custody. (Washington Post, 8 June 1990, A1; 19 June 1990, A1) |

| June 25-26, 1990 | Mandela meets with Bush at White House, addresses Congress, urges both to keep sanctions in place. EC leaders reject Thatcher’s suggestion of immediate lifting of some sanctions, but say they would consider “gradual relaxation” of sanctions “when there is further clear evidence that the process of change already initiated continues.” In South Africa, right-wing leaders call for early elections, claiming that de Klerk has no mandate for his reforms. (Washington Post, 26 June 1990, A1; 27 June 1990, A23; Financial Times, 27 June 1990, 1) |

| August— September 1990 | Violence in Natal escalates, spreads to Soweto, other Johannesburg townships. After 500 people are killed in 12-day period, South African government declares areas of greatest violence to be “unrest areas,” imposes restrictions, grants police powers similar to those under state of emergency. ANC criticizes move, charges police are siding with Inkatha against ANC, trying to promote tribal strife, weaken ANC in negotiations. In September, Inkatha attacks workers’ hostel, with support from police and army units, killing at least 34 persons, wounding many more. Claiming that white extremists are fanning violence to undermine negotiations, Mandela says ANC may have to resume its armed struggle if killing does not stop soon. (Washington Post, 25 August 1990, A6; 5 September 1990, A21; 12 September 1990, A16) |

| September 23-25, 1990 | De Klerk becomes first South African head of state to visit Washington in 45 years. Following meeting at White House, administration officials say South Africa has met two of CAAA’s five conditions—lifting ban on political parties, agreeing to enter good-faith negotiations with black opposition—and Bush says he would ask Congress to lift or modify sanctions if two more conditions are met—lifting state of emergency in Natal, freeing all political prisoners. (CAAA gives president discretion to lift some or all sanctions if four of five conditions outlined in the act are met, fifth being repeal of the two main pillars of apartheid: Group Areas Act, Population Registration Act.) Meeting with members of Congress, de Klerk says he wants to move to American-style democracy based on principle of one man, one vote, although combined with guarantees to protect white minority. (New York Times, 25 September 1990, A1; 26 September 1990, A3) |

| October 4, 1990 | Deputy Constitutional Minister Roelf Meyer says South African government has dropped idea of “group rights” in postapartheid political system, that whites will have to depend on other “mechanisms,” such as strong bill of rights, strong regional governments, political parties to protect their rights. (Washington Post, 5 October 1990, A29) |

| October 15, 1990 | Repeal of Separate Amenities Act becomes effective. However, officials in many small towns, villages say they will use Group Areas Act (which bars blacks from residing in white areas), other municipal regulations to continue barring blacks from using public libraries, swimming pools, other public facilities. For example, farming town of Bethal says it will require nonresidents (i.e. blacks) to pay prohibitively expensive membership fee to use public library. (Financial Times, 15 October 1990, 24) |

| December 1990 | EC leaders in Rome vote to allow new investments in South Africa to acknowledge the political reforms of the past year, but state remaining sanctions stay in place because “the basic institutions of apartheid are still firmly in place.” (Washington Post, 16 December 1990, A1) |

| February 1991 | EC foreign ministers agree to lift economic sanctions once the South African Parliament repeals three basic apartheid laws, as has been requested by South African President Frederick W. de Klerk. (Washington Post, 9 February 1991, A9). |

| February 9, 1991 | Mandela threatens to “unleash a wave of ‘mass action'” (street demonstrations, rallies, boycotts) to make new investment in South Africa impossible if the United States and European governments lift sanctions. (Washington Post, 9 February 1991, A9) |

| February 17, 1991 | Nine-nation Commonwealth committee decides to maintain all trade, financial and sporting sanctions until South Africa takes more concrete steps toward the abolition of apartheid. (Financial Times, 18 February 1991, 4) |

| Early June 1991 | South Africa parliament repeals the Land Act, Group Areas Act and the Population Registration Act and releases several political prisoners. (Banks, Day, Muller 768) |

| July 9, 1991 | The International Olympic Committee ends its 21-year ban on South African participation in the Olympics. The International Cricket Council in London votes to recognize the United Cricket Board of South Africa. This follows urging by the British Prime Minister John Major for the world to gradually welcome Pretoria back to international sports. (Observer, 10 July 1991, 1; New York Times, 11 July 1991, A1) |

| July 10, 1991 | Concluding that it has met the 5 conditions in the CAAA, President Bush lifts US sanctions against South Africa. Mandela criticizes decision, says US should wait for more progress toward the elimination of apartheid before lifting the sanctions. Top Democratic leaders, the Congressional Black Caucus, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People all oppose the decision. To counter his domestic critics, Bush announces a doubling of US assistance to black South Africans from $40 million to $80 million. However, the US continues to oppose loans for South Africa in multilateral institutions, and a ban on nuclear trade and the arms embargo also remain in place. (Financial Times, 11 July 1991, 14; New York Times, 11 July 1991, A1; Facts on File, 14 July 1991, 505 A1) |

| October 23, 1991 | Japan lifts economic sanctions against South Africa. (Financial Times, 23 October 1991, 9) |

| April 7, 1992 | The EC lifts its ban on oil sales to South Africa, and votes to encourage resumption of more sports, cultural and scientific links. The only remaining EC sanctions on South Africa now are the UN Security Council ban on the sale of arms and the exchange of military attaches. (Financial Times, 7 April 1992, 4) |

| February 3, 1993 | Norway announces it will partially lift its economic and trade sanctions against South Africa on March 15 but maintain its embargo on oil and weapons sales. (Financial Times, 24 February 1993, 4) |

| May 25, 1993 | The World Bank announces that $1 billion worth of development projects will be available for South Africa once a multiracial transitional government is installed. (Financial Times, 25 May 1991, 4) |

| July 15, 1993 | The Clinton administration plans to urge state and local governments to lift their economic sanctions against South Africa (International Trade Reporter, 21 July 1993, 1194) |

| August 1993 | The State of Massachusetts threatens Digital Equipment Corporation with sanctions for its decision to start doing business in South Africa. 165 US counties, cities and states maintain some type of penalty against companies doing business in South Africa. (Journal of Commerce, 13 August 1993, 3A) |

| September 13, 1993 | India announces it will lift trade sanctions against South Africa this month and may soon establish diplomatic ties with Pretoria. (Financial Times, 13 September 1993, 1) |

| September 25, 1993 | The day after the South African parliament approves the creation of a multiracial Transitional Executive Council, Nelson Mandela announces to the United Nations that the end to apartheid is in sight. In a speech to the UN Special Committee on Apartheid, he states, “we therefore extend an earnest appeal to you the governments, and the peoples you represent, to end the economic sanctions you imposed and which have brought us to the point where the transition to democracy has now been enshrined in the law of our country.” (Financial Times, 25 September 1993, 1) |

| September 29, 1993 | Members of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) vote to lift economic sanctions against South Africa, except for the UN mandated arms embargo. OAU countries will also maintain a ban on oil sales and nuclear technologies to Pretoria. (Financial Times, 27 January 1993, 4) |

| October 1993 | The UN General Assembly agrees to remove the oil embargo when the transitional executive council becomes operational. The arms embargo will remain in place. (New York Times, 9 October 1993, 8) |

| October 15, 1993 | Nelson Mandela and President de Klerk are awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. (Banks, Day, Muller 771) |

| November 23, 1993 | President Clinton signs into law a bill repealing all remaining federal anti-apartheid sanctions, except for the arms embargo and restrictions on transfers of nuclear technology. Lifted sanctions include: ban on aid; ban on OPIC and Export-Import Bank programs; trade restrictions including inegibility for MFN status. The law also calls on local governments to repeal their own sanctions before October 1995. If they fail to do so by that date, they risk the loss of federal transportation funds. (Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, 27 November 1993, 3281) |

| May 10, 1994 | Nelson Mandela is inaugurated as the first democratically-elected president of South Africa. (Christian Science Monitor, 10 May 1994, 1) |

| June 1994 | UN Security Council lifts its 1977 arms embargo against South Africa. Pretoria is also allowed to reactivate its membership to the UN General Assembly and UN specialized agencies. (Banks, Day, Muller 771) |

| February 27, 1998 | After settling a dispute with Pretoria over the extradition of South Africans involved in illegal arms deals, the US lifts its 35-year old arms embargo against South Africa, the last remaining sanction imposed at the beginning of the apartheid era. (New York Times, 28 February 1998, A4) |

http://www.iie.com/research/topics/sanctions/southafrica.cfm