A British Businessman in South Africa, Member of Parliament in the Cape Colony, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, imperialist, acquired a British Royal Charter, formed the British South African Company (BSAC) that colonized Zimbabwe.

The Early Years

Cecil John Rhodes was born on 5 July 1853 in the small hamlet of Bishop’s Stortford, England. He was the fifth son of Francis William Rhodes and his second wife, Louisa Peacock. A priest of the Church of England, his father served as curate of Brentwood Essex for fifteen years, until 1849, when he became the vicar of Bishop’s Stortford, where he remained until 1876. Rhodes had nine brothers and two sisters and attended the grammar school at Bishop’s Stortford. When he was growing up Rhodes read voraciously but vicariously, his favourite book being The Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, but he equally adored the highly esteemed historian Edward Gibbon and his works on the great Roman Empire.

Cecil Rhodes as a boy.Source

Cecil Rhodes as a boy.Source

Rhodes fell ill shortly after leaving school and, as his lungs were affected, it was decided that he should visit his brother, Herbert, who had recently immigrated to Natal. It was also believed, by both Rhodes and his father, that the business opportunities offered in South Africa would be able to provide Rhodes with a more promising future than staying in England. At the tender age of 17 Rhodes arrived in Durban on 1 September 1870. He brought with him three thousand pounds that his aunt had lent him and used it to invest in diamond diggings in Kimberley.

After a brief stay with the Surveyor-General of Natal, Dr. P. C. Sutherland, in Pietermaritzburg, Rhodes joined his brother on his cotton farm in the Umkomaas valley in Natal. By the time Rhodes arrived at the farm his brother had already left the farm to travel 650 kilometres north, to the diamond fields in Kimberley. Left on his own Rhodes began to work his brother’s farm, growing and selling its cotton, proving himself to be an astute businessman despite his young age. Cotton farming was not Rhodes’ passion and the diamond mines beckoned. At 18, in October 1871, Rhodes left the Natal colony to follow his brother to the diamond fields of Kimberley. In Kimberley he supervised the working of his brother’s claim and speculated on his behalf. Among his associates in the early days were John X Merriman and Charles D. Rudd, of the infamous Rudd Concession, who later became his partner in the De Beers Mining Company and the British South Africa Company.

In 1872 Rhodes suffered a slight heart attack. Partly to recuperate, but also to investigate the prospects of finding gold in the interior, the Rhodes brothers trekked north by ox wagon. Their trek took them along the missionary road in Bechuanaland as far north as Mafeking, then eastwards through the Transvaal as far as the Murchison range. The journey inspired a love of the country in Rhodes and marked the beginning of his interest in the road to the north and the northern interior itself.

In 1873 Rhodes left his diamond fields in the care of his partner, Rudd, and sailed for England to complete his studies. He was admitted to Oriel College Oxford, but only stayed for one term in 1873 and only returned for his second term in 1876. He was greatly influenced by John Ruskin’s inaugural lecture at Oxford, which reinforced his own attachment to the cause of British Imperialism. Among his Oxford associates were Rochefort Maguire, later a fellow of All Souls and a director of the British South Africa Company, and Charles Metcalfe. At university Rhodes was also taken up with the idea of creating a ‘secret society’ of British men who would be able to lead the world, and spread to all corners of the globe the spirit of the Englishman that Rhodes so admired. He wrote of this society,

Why should we not form a secret society with but one object the furtherance of the British Empire and the bringing of the whole uncivilised world under British rule for the recovery of the United States for the making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire.’

His university career engendered in Rhodes his admiration for the Oxford ‘system’ which was eventually to mature in his scholarship scheme: ‘Wherever you turn your eye – except in science – an Oxford man is at the top of the tree’.

An Arch Imperialist

One of Rhodes’ guiding principles throughout his life, that underpinned almost all of his actions, was his firm belief that the Englishman was the greatest human specimen in the world and that his rule would be a benefit to all. Rhodes was the ultimate imperialist, he believed, above all else, in the glory of the British Empire and the superiority of the Englishman and British Rule, and saw it as his God given task to expand the Empire, not only for the good of that Empire, but, as he believed, for the good of all peoples over whom she would rule. At the age of 24 he had already shared this vision with his fellows in a tiny shack in a mining town in Kimberley, when he told them,

‘The object of which I intend to devote my life is the defence and extension of the British Empire. I think that object a worthy one because the British Empire stands for the protection of all the inhabitants of a country in life, liberty, property, fair play and happiness and it is the greatest platform the world has ever seen for these purposes and for human enjoyment’.

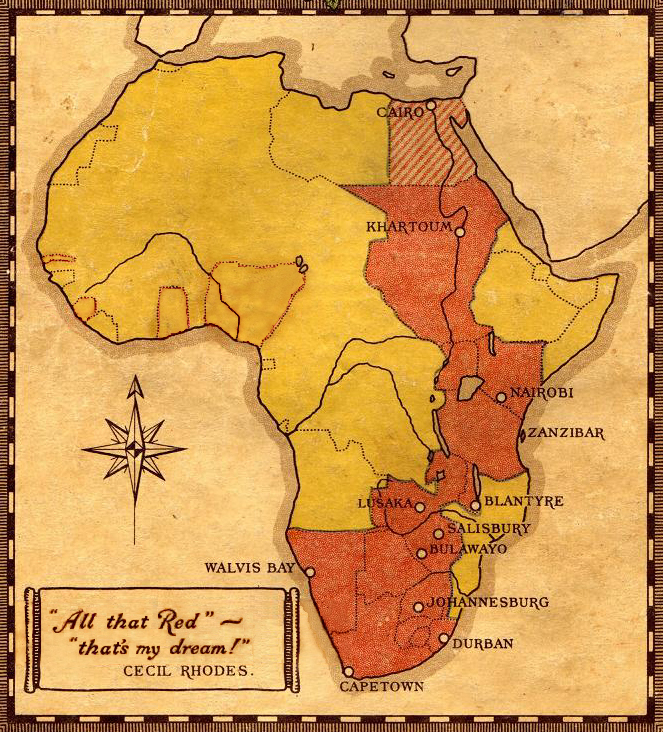

Rhodes’ British Empire corridor through Africa. Source

Rhodes’ British Empire corridor through Africa. Source

A few months later, in a confession written at Oxford in 1877, Rhodes articulated this same imperial vision, but with words that clearly showed his disdain for the people whom the British Empire should rule:

“I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. Just fancy those parts that are at present inhabited by the most despicable specimen of human being, what an alteration there would be in them if they were brought under Anglo-Saxon influence…if there be a God, I think that what he would like me to do is paint as much of the map of Africa British Red as possible…”

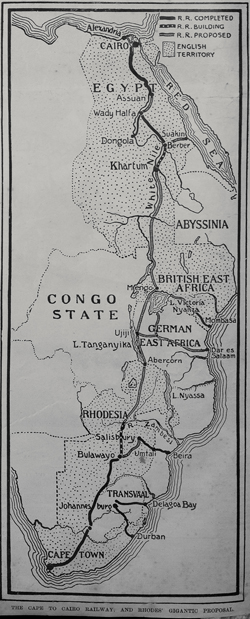

One of Rhodes’ greatest dreams was a ribbon of red, demarcating British territory, which would cross the whole of Africa, from South Africa to Egypt. Part of this vision was his desire to construct a Cape to Cairo railway, one of his most famous projects. It was this expansive vision of British Imperial control, and the great lengths that Rhodes went to in order to fulfil this vision, which led many of his contemporaries and his biographers to mark him as a great visionary and leader.

Rhodes was both ruthless and incredibly successful in his pursuit of this scheme of a great British Empire. His contemporaries marvelled both at his prowess and incredible energy and capacity, but they also shuddered at his callousness and depravity in all his pursuit. His contemporaries, both awed and appalled by the man, wrote of him as a man of original ideas who sought more than the mere ‘getting and spending which limits the ambitions and lays waste the powers of the average man’. Yet although many people at the time saw Rhodes as a man of great vision, an unconquerable leader with the ability to pursue his aims across the vast African continent, there were nonetheless dissident voices who were shocked by Rhodes’ actions and those of his British South Africa Company. One such voice was that of Olive Schreiner, who, initially awed by Rhodes, had come to abhor him. In April of 1897 she wrote, in a letter to her friend, John Merriman:

“We fight Rhodes because he means so much of oppression, injustice, & moral degradation to South Africa; – but if he passed away tomorrow there still remains the terrible fact that something in our society has formed the matrix which has fed, nourished, built up such a man!”

The King of Diamonds

Rhodes’ plans for the Cape To Cairo Railway, 1899 Source

Rhodes’ plans for the Cape To Cairo Railway, 1899 Source

Whilst at Oxford, Rhodes continued to prosper in Kimberley. Before his departure for Oxford Rhodes had realised that the changing laws in the Kimberley area would force the ‘small man’ out of the diamond fields and would only leave larger companies able to operate in the mines. In light of this he sought to consolidate a number of mines with his partner, Charles Rudd. Rhodes had also decided to move away from the ‘New Rush’ Kimberley mine fields, that were higher in the ground and thus more accessible, back to the lower yielding ‘Old Rush’ area. Here Rhodes and Rudd bought the costly claim of what was known as old De Beers (Vooruitzicht Farm) which owed its name to Johannes Nicolaas de Beer and his brother, Diederik Arnoldus de Beer, the original owners of the farm Vooruitzicht. It was this farm that would lend its name to Rhodes and Rudd’s ever growing diamond company.

In 1874 and 1875 the diamond fields were in the grip of depression, but Rhodes and Rudd were among those who stayed to consolidate their interests. They believed that diamonds would be numerous in the hard blue ground that had been exposed after the softer, yellow layer near the surface had been worked out. During this time the technical problem of clearing out the water that was flooding the mines became serious and he and Rudd obtained the contract for pumping the water out of the three main mines.

Rhodes had come to the realisation that the only way to avoid the cyclical boom and bust of the diamond industry was to have far greater control over the production and distribution of diamonds. And so, in April 1888, in search of an oligopoly over diamond production, Rhodes and Rudd launched the De Beers Consolidated Mines mining company. With 200 000 pounds capital the Company, of which Rhodes was secretary, owned the largest interest in mines in South Africa. Rhodes greatest coup was to get Barney Barnato, owner of the Kimberley mine, to go partnership with Rhodes’ De Beers Company. Of the encounter Barnato later wrote:

“When you have been with him half an hour you not only agree with him, but come to believe you have always held his opinion. No one else in the world could have induced me to into this partnership. But Rhodes had an extraordinary ascendancy over men: he tied them up, as he ties up everybody. It is his way. You can’t resist him; you must be with him.”

With his acquisition of most of the world’s diamond mines Rhodes became an incredibly rich man. But Rhodes was not after wealth for wealth’s sake, he was acutely aware of the relationship between money and power, and it was power which he sought. Hans Sauer wrote of a conversation he had had with Rhodes whilst looking over the Kimberley diamond mine, where Sauer had asked Rhodes, ‘what do you see here?’, and, Sauer writes, ‘with a slow sweep of his hand, Rhodes answered with the single word: “Power”.’

In the early 1880s gold was discovered in the Transvaal, sparking the Witwatersrand Gold Rush. Rhodes considered joining the rush to open gold mines in the region, but Rudd, convinced him that the Witwatersrand was merely the beginning, and that far greater gold fields lay to the north, in present day Zimbabwe and Zambia. As a result Rhodes held back while other Kimberley capitalists hastened to the Transvaal to stake the best claims. In 1887 when Rhodes finally did act and formed the Goldfields of South Africa Company with his brother Frank, most of the best claims were already taken. Goldfields South Africa performed very poorly, prompting Rhodes to look towards the north for the gold fields that Rudd had assured him were lying in wait.

The Statesman

In 1880 Rhodes prepared to enter public life at the Cape. With the incorporation of Griqualand West into the Cape Colony in 1877 the area obtained six seats in the Cape House of Assembly. Rhodes chose the constituency of Barkley West, a rural constituency in which Boer voters predominated, and at age 29 was elected as its parliamentary representative. Barkley West remained faithful to Rhodes even after the Jameson Raid and he continued as its member until his death.

The chief preoccupation of the Cape Parliament when Rhodes became a member was the future of Basutoland, where the ministry of Sir Gordon Sprigg was trying to restore order after a rebellion in 1880. The ministry had precipitated the revolt by applying its policy of disarmament to the Basuto. Seeking expansion to the north and with prospects of building his great dream of a Cape to Cairo railway, Rhodes persuaded Britain to establish a protectorate over Bechuanaland (now Botswana) in 1884, eventually leading to Britain annexing this territory.

Rhodes seemed to have immense influence in Parliament despite the fact that he was acknowledged to be a poor speaker, with a thin, high pitched voice, with little aptitude for oration and a poor physical presence. What made Rhodes nonetheless so incredibly convincing to his contemporaries has remained much of a mystery to his biographers.

The Push for Mashonaland

Rhodes’ imperial vision for Africa was never far from his mind. In 1888 Rhodes looked further north towards Matabeleland and Mashonaland, in present day Zimbabwe. Matabeleland fell squarely in the territory which Rhodes hoped to conquer, from the Cape to Cairo, in the name of the British Empire. It also was believed to hold vast, untapped gold fields, which Rudd believed would be of far greater value than those discovered in the Witwatersrand.

In pursuit of his imperial dream and in his desire to make up for the failure of his Gold Fields Mining Company, Rhodes began to explore ways in which to exploit the mineral wealth of Matabeleland and Mahsonaland. The King of Matabeleland, King Lobengula, who was believed by the British to also rule over Mashonaland, had already allowed a number of British miners mineral rights in his kingdom. He had also sent a number of his men to labour in the diamond mines, thus setting a precedence for engagement with him. However, the King had consistently stated quite clearly that he wanted no British interference in his own territory.

In 1887 Lobengula signed a treaty with the Transvaal Government, an act that convinced Rhodes that the Boere were trying to steal ‘his north’. By this stage the ‘scramble for Africa’ was also already well under way and Rhodes became convinced that the Germans, French and Portuguese were going to try to take Matabeleland. These fears made Rhodes rapidly mobilise in order to get Matabeleland under British control. Although the British government at the time was against further colonial expansion to the north of South Africa, Rhodes was able to use the threat of other imperial powers, such as Germany, taking over the land to push the British Government to take action.

The Government sent John Smith Moffat, the then Assistant Commissioner to Sir Sidney Shippard in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) who was well known to the Matabele Chief Lobengula as their fathers were friends, to negotiate a treaty with Lobengula. The result was the Moffat Treaty of February 1888, essentially a relaxed British protection treaty. The Moffat Treaty was however between Lobengula and the British Government, Rhodes himself was hardly a relevant player in this. Worried that the Moffat Treaty was too weak to hold Matabeleland, and convinced that the Dutch and Germans were making plans to take the territory and desperate for exclusive mining rights in the region, Rhodes concocted to his own plan to take control of the territory. With his business partner Rudd, Rhodes formed the British South Africa Company (BSAC), crafted on the British and Dutch East India company models. The BSAC was a commercial-political entity aiming at exploiting economic resources and political power to advance British finance capital.

Shortly after the Moffat Treaty, in March 1888, Rhodes sent his business partner Charles Rudd to get Lobengula to sign an exclusive mining concession to the British South Africa Company. When Rudd arrived at Lobengula’s kraal however, there were a number of other British concession hunters already there, seeking to undertake the exact same manoeuvre as Rhodes’ BSAC. Through Rhodes influence however, Rudd was able to win over the support of the local British officials staying with Lobengula, a move which ultimately convinced Lobengula that Rudd had more power and influence than any of the other petitioners seeking concessions from him.

After much negotiation Rudd was eventually able to get Lobengula to sign a concession giving exclusive mining rights to the BSAC in exchange for protection against the Boere and neighbouring tribes. This concession became known as the Rudd Concession. Lobengula’s young warriors were angry and inflamed and were itching to kill the white men who were entering their lands. Lobengula however feared his people would be defeated if they attacked the whites, and so it is likely that he signed the Rudd Concession in the hopes of gaining British protection and thereby preventing a Boer migration into his lands which would then incite his warriors to battle. For Lobengula his options were essentially to either concede to the British or to the Dutch. In the belief that he was protecting his interests he sided with the seemingly more lenient and liberal British. Like so many documents signed by Africans during the colonial period, the Rudd Concession was however not what it claimed to be, but rather became a justifying document for the colonisation of theNdebele and the Shona.

Using the Rudd Concession, despite initial protests by the British Government, Rhodes managed to acquire a Royal Charter (approval from the British monarch) for his British South Africa Company. The Royal Charter allowed Rhodes to act on behalf of British interests in Matabeleland. It gave the company full imperial and colonial powers as it was allowed to create a police force, fly its own flag, construct roads, railways, telegraphs, engage in mining operations, settle on acquired territories and create financial institutions.

Rhodes convinced the British Government to give his company the right to control those parts of Matabeleland and Mashonaland that were ‘not in use’ by the African residents there and to provide ‘protection’ for the Africans on the land that was reserved for them. This proposal, which would cost the British taxpayer nothing but would extend the reaches of the British Empire, eventually found favour in London. The charter was officially granted on 29 October 1889. For Rhodes is BSAC with its Royal charter was the means whereby which to expand the British Empire, which a timid government and penurious British treasury were not about to accomplish

Rhodes reclining on one of his many voyages to the north. Source

Rhodes reclining on one of his many voyages to the north. Source

After gaining his charter from the British Government Rhodes and his compatriots in the BSAC essentially felt that Matabeleland and Mashonaland were now under their control. Rhodes felt that war with the Ndebele was inevitable and would not allow his plans for extending the British Empire to be thwarted by “a savage chief with about 8 000 warriors”. Rhodes was determined that white settlers would soon occupy Matabeleland and Mashonaland, and the Ndebele could not resist them.

To gain power over Matabeleland and Mashonaland Rhodes hired Frank Johnson and Maurice Heany, two mercenaries, to raise a force of 5 00 white men who would support BammaNgwato, enemies of Lobengula’s, in an attack on Lobengula’s kraal. Johnson offered to deliver to Rhodes the Ndebele and Shona territory in nine month for £87 500. Johnson was joined by Frederick Selous, a hunter with professed close knowledge of Mashonaland. Rhodes advised Johnson to select as recruits primarily the sons of rich families, with the intention that, if the attack did fail and the British were captured, the British Government would be left with no choice but to send armed forces into Matabeleland to rescue the sons of Britain’s elite. In the end Johnson’s attack was called off because Rhodes had received news that Lobengula was going to allow Rhodes’ men into Matabele and Mashonaland without any opposition.

Despite Lobengula capitulating and giving permission for vast numbers of BSAC miners to enter his territory, Rhodes calculated a new plan to gain power in the region. In 1890 Rhodes sent a ‘Pioneer Column’ into Mashonaland, a column consisting of around 192 prospecting miners and around 480 armed troopers of the newly formed British South Africa Company Police, who were ostensibly there to ‘protect’ the miners. By sending in this column, Rhodes had deviously planned a move which would either force Lobengula to attack the settlers and then be crushed, or force him to allow a vast military force to take seat in his country. In the words of Rutherfoord Harris, a compatriot of Rhodes:

“….if he attack us, he is doomed, if he does not, his fangs will be drawn and the pressure of civilisation on all his border will press more and more heavily upon him, and the desired result, the disappearance of the Matabele as a power, if delayed is yet the more certain.”

The men who formed part of the Pioneer Column were all promised both gold concessions and land if they were successful in settling in Mashonaland.

On 13 September 1890, a day after the Pioneer Column arrived in Mashonaland,Rhodes’s BSAC invaded and occupied Mashonaland without any resistance from Lobengula. They settled at the site of what was later to become the town of Salisbury, present day Harare, marking the beginning of white settler occupation on the Zimbabwean plateau. They raised the Union Jack (the British national flag) in Salisbury, proclaiming it British territory.

The prospectors and the company had hoped to find a ‘second Rand’ from the ancient gold mines of the Mashona, but the gold had been worked out of the ground long before. After failing to find this perceived ‘Second Rand’, Rhodes, instead of allowing the settlers mining rights, as had been agreed to by Lobengula, granted farming land to settler pioneers, something which went expressly against the Rudd Concession.

The end of the Matabele

In conceding Mashonaland to the BSAC Lobengula had avoided going to war with the British and had kept his people alive, and much of his territory intact. But unfortunately he had only been able to delay the inevitable. With no gold was found in Mashonaland, Rhodes’ BSAC was facing complete financial ruin. Leander Jameson suggested to Rhodes that ‘getting Matabeleland open would give us a tremendous life in shares and everything else’. Gaining the Matabeleland territory would also play directly into Rhodes megalomaniac vision of expanding the British Empire across Africa.

And so, in 1893, the BSAC eventually clashed with the Ndebele, in what Rhodes had perceived as an inevitable war. The settlers justified their initial attacks against the Ndebele to the British Government by arguing that they were protecting the Shona against the ‘vicious’ and ‘savage’ Ndebele impis. This was however a ploy, consciously concucted by Jameson in conjunction with Rhodes, in order to ensure that the British Government would not object to their further intrusions into Matabeleland by creating the impression that the Ndebele were the first aggressors. To fight their war the company recruited large bands of young mercenaries who were promised land and gold in exchange for their fighting power.

The final blow any hopes that the Ndebele might avoid war, came when Jameson was able to convince the British Government that Lobengula had sent a massive impi of 7 000 men into Mashonaland, who then gave Jameson leave to engage in defensive tactics. There is no indication that the impi Jamseon reported on had ever existed. Lobengula himself, in a last appeal to the legal/rational system the British seemed to so fervently uphold, wrote to the British High Commissioner saying, “Every day I hear from you reports which are nothing but lies. I am tired of hearing nothing but lies. What Impi of mine have your people seen and where do they come from? I know nothing of them.”

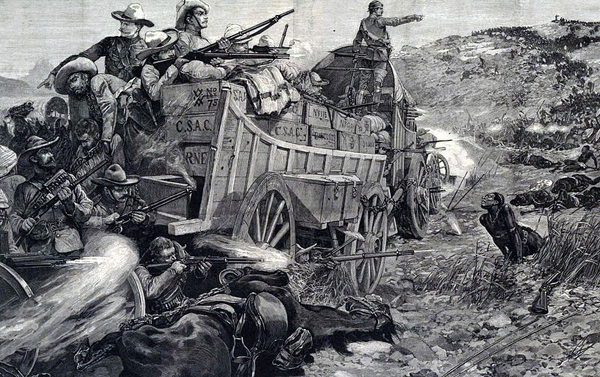

An artist’s impression of the British battling against the Ndebele Source

An artist’s impression of the British battling against the Ndebele Source

It was however far too late for Lobengula. With the permission to engage in defensive action from the British Government Rhodes joined Jameson in Matabeleland and his group of mercenary soldiers struck a quick and fatal blow at the Ndebele. Rhodes’ mercenaries were in possession of the latest in munitions technology, carrying with them into the veld maxim guns, which, like machine guns, could fire rapid rounds. The Ndebele Impis were helpless in the face of this brutal killing technology and were slaughtered in their thousands. Lobengula himself realised he could not face the British in open combat and so he burnt down his own capital and fled with a few warriors. He is presumed to have died shortly afterwards in January of 1894 from ill health.

The war against the Matabele, fought mostly by voluntary mercenaries, cost around £66 000. Most of the money to pay for this war came directly from Rhodes Consolidated Goldfields Company, which by this point had begun to produce excellent yields from the deeper lying gold fields. The conquered lands were named Southern and Northern Rhodesia, to honour Rhodes. Today, these are the countries of Zimbabwe and Zambia. By the 1890s these conquered territories were being called Southern and Nothern Rhodesia.

The Precursor to Apartheid

In July 1890 Rhodes became the Prime Minister of the Cape colony, after getting support from the English-speaking white and non-white voters and a number of Afrikaner-bond, whom he had offered shares in the British South Africa Company. One of Rhodes most notorious and infamous undertakings as Prime Minister in South Africa, was his institution of the Glen Grey Act, a document that is often seen as the blueprint for the Apartheid regime that was to come.

On 27 July 1894, Rhodes gave a rousing speech, full of arrogance and optimism, to the Parliament of Cape Town that lasted more than 100 minutes. In this speech Rhodes was opening debate on the ‘Native’ Bill that he had been working on for two years. The bill had initially been intended merely as an administrative act to bring more order to the overcrowded eastern Cape district of Glen Grey, but in his typical fashion Rhodes had turned this routine administrative task into something far bigger, the formulation of what he described as a ‘Native Bill for Africa’. In much of his speech Rhodes set out, in clear cut terms, the chief purpose of his ‘Native Bill’, to force more Africans into the wage-labour market, a pursuit which would undoubtedly also help Rhodes in his own mining claims in Kimberley and the Transvaal.

Rhodes opened his speech on the Glen Grey Act with the following words:

‘There is, I think, a general feeling that the natives are a distinct source of trouble and loss to the country. Now, I take a different view. When I see the labour troubles that are occurring in the United States, and when I see the troubles that are going to occur with the English people in their own country on the social question and the labour question, I feel rather glad that the labour question here is connected with the native question.’

He then continued,

‘The proposition that I would wish to put to the House is this, that I do not feel that the fact of our having to live with the natives in this country is a reason for serious anxiety. In fact, I think the natives should be a source of great assistance to most of us. At any rate, if the whites maintain their position as the supreme race, the day may come when we shall all be thankful that we have the natives with us in their proper position….. I feel that I am responsible for about two millions of human beings. The question which has submitted itself to my mind with regard to the natives is this ”” What is their present state ? I find that they are increasing enormously. I find that there are certain locations for them where, without any right or title to the land, they are herded together. They are multiplying to an enormous extent, and these locations are becoming too small…. The natives there are increasing at an enormous rate. The old diminutions by war and pestilence do not occur… W e have given them no share in the government ”” and I think rightly, too ”” and no interest in the local development of their country. What one feels is that there are questions like bridges, roads, education, plantations of trees, and various local questions, to which the natives might devote themselves with good results. At present we give them nothing to do, because we have taken away their power of making war ”” an excellent pursuit in its way ”” which once employed their minds…. We do not teach them the dignity of labour, and they simply loaf about in sloth and laziness. They never go out and work. This is what we have failed to consider with reference to our native population… What I would like in regard to a native area is that there should be no white men in its midst. I hold that the natives should be apart from white men, and not mixed up with them… The Government looks upon them as living in a native reserve, and desires to make the transfer and alienation of land as simple as possible… We fail utterly when we put natives on an equality with ourselves. If we deal with them differently and say, ” Yes, these people have their own ideas,” and so on, then we are all right ; but when once we depart from that position and put them on an equality with ourselves, we may give the matter up… As to the question of voting, we say that the natives are in a sense citizens, but not altogether citizens ”” they are still children….’

The Glen Grey Act was to pressure Africans to enter the labour market firstly by severely restricting African access to land and landownership rights so that they could not become owners of the means of production, and secondly by imposing a 10 shilling labour tax on all Africans who could not prove that they had been in ‘bona fide’ wage employment for at least three months in a year. This land shortage coupled with a tax for not engaging in wage labour would push thousands of Africans into the migrant labour market. These were all measures essentially designed to ensure a system of labour migration which would feed the mines in both Kimberley and the Rand with cheap migrant labour. This section of the act instigated the terrible migrant-labour system that was to be so destructive in 20th century South Africa.

Another pernicious outcome of the Glen Grey Act was its affected on African land rights claims and restricted and controlled where they could live. According to the act ‘natives’, as African peoples were then termed, were no longer allowed to sell land without the permission of the governor, nor where they allowed to divide or sublet the land or give it as inheritance to more than one heir. The act also laid out that the Glen Grey area and the Transkei should remain “purely native territories”. This act was eventually to become the foundation of the 1913 Natives Land Act, a precursor to much of the Apartheid policy of separate development and the creation of the Bantustans.

Lastly the Glen Grey Act radically reduced the voting franchise for Africans. One of Rhodes primary policies as Prime Minister was to aim for the creation of a South African Federation under the British flag. A unified South Africa was an incredibly important political goal for Rhodes, and so when the Afrikaner Bondsmen came to Rhodes to complain about the number and rise of propertied Africans, who were competing with the Afrikaners and characteristically voted for English, rather than Afrikaans, representative. In response to the Afrikaners’ complaints, Rhodes decided to give them, in the Glen Grey Act, a policy which would disenfranchise the Africans competing with Afrikaners whilst also ensuring Africans could not own farms which would compete with the Afrikaners.

To disenfranchise Africans the Act raised the property requirements for the franchise and required each voter to be able to write his own name, address and occupation before being allowed to vote. This radically curtailed the number of Africans who could vote, essentially marking the beginning of the end for the African franchise. This new law allowed for the voter-less annexation of Pondoland. The Glen Grey Act also denied the vote to Africans from Pondoland no matter their education or property. Through the adoption of the Act, Rhodes managed to gradually persuade Parliament to abandon Britain’s priceless nineteenth-century ideal that in principle all persons, irrespective of colour, were equal before the law.

The Glen Grey Act was vigorously opposed by the English speaking members of the Cape Parliament, but Rhodes, with his forceful character, was able to push the act through Parliament, and in August 1984 Rhodes’ Glen Grey Act became law. The Glen Grey Act, which created the migrant labour system, formalised the ‘native reserves’ and removed the franchise of almost all Africans, is seen by many as lying the ground work for the Apartheid system of the 20th century.

The Fall of Giants

By 1895, at the height of his powers, Rhodes was the unquestioned master of South Africa, ruling over the destiny of the Cape and its white and African subjects, controlling nearly all of the world’s diamonds and much of its gold, and effectively ruling over three colonial dependencies in the heart of Africa.

‘The Rhodes Colosuss striding from Cape Town to Cairo’, from Punch Magazine, 1892 Source

‘The Rhodes Colosuss striding from Cape Town to Cairo’, from Punch Magazine, 1892 Source

Although Rhodes’ policies were instrumental in the development of British imperial policies in South Africa, he did not, however, have direct political power over the Boer Republic of the Transvaal. He often disagreed with the Transvaal government’s policies and felt he could use his money and his power to overthrow the Boer government and install a British colonial government supporting mine-owners’ interests in its place. In 1895, Rhodes precipitated his own spectacular fall from power when he supported an attack on the Transvaal under the leadership of his old friend, Leander Jameson. It was a complete failure and Rhodes had to resign as Prime Minister of the Cape and head of the British South Africa Company in January 1896. After having befriended the Afrikaners for so many years, Rhodes’ support of the Jameson Raid and his attempts to get the miners in Johannesburg to rise up in a coup against the leaders of the Transvaal, were seen by the Bondsmen and Afrikaners as a complete betrayal, and Rhodes’ hopes of ever uniting South Africa under one flag were dashed against the rocks.

Despite his meteoric loss of power and prestige Rhodes nonetheless continued his political activities. In mid 1896 the Shona and Ndebele people in Southern Rhodesia, present day Zimbabwe, rose up against their colonial oppressors in a bid for freedom. Rhodes personally travelled to the region to take charge of the colonial response. In his attacks on the Ndebele and Shona he was vindictive, resorting to a scorched earth policy and destroying all their villages and crops.

After months of fighting Rhodes decided that conciliation was the only option. Looking to negotiate a peace settlement with the Ndebele and Shona he headed into the Matopo Mountains where a great indaba was held. Rhodes asked the chiefs why the Africans had risen up in war against the colonisers. The chiefs replied that the Africans had for decades been humiliated by the white settlers, subjected to police brutality and pushed into forced labour. Rhodes listened to the complaints and told the chiefs, “All that is over”. The chiefs saw this as a promise that the conditions for them and their countrymen would be improved, and so they agreed with Rhodes that they would end their hostilities. As a part of their agreement Rhodes spent many days in the Matopo hills, and every day the Ndebele would come to him and voice all their complaints. In belief that their worries and complaints would be given just recognition, the Ndebele and Shona chiefs laid down their arms and returned to their fields. When he left Rhodes was lauded by the people whose suffering by the hands of colonists was only to increase in the next century, as the ‘Umlamulanmkunzi’, the peacemaker.

Thereafter, Rhodes was in ill-health, but he began concentrating on developing Rhodesia and especially in extending the railway, which he dreamed would one day reach Cairo, Egypt.

After the Anglo-Boer war that broke out in October 1899, Rhodes rushed to Kimberley to organise the defence of the town. However, his health was worsened by the siege, and after travelling to Europe he returned to the Cape in February 1902. He died on 26 March 1902 at Muizenberg in the Cape Colony (now Cape Town). Reportedly some of his last words were, ‘so little done, so much to do’. Rhodes was buried at the Matopos Hills, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). He left £6 million (approx USD 960 million in 2015), most of which went to Oxford University to establish the Rhodes scholarships to provide places at Oxford for students from the United States, the British colonies, and Germany.

Rhodes never married and he did not have any known children and there is some suggestion that he was homosexual. This suggestion is based on the care and concern he showed to some men, but it is not enough to offer any solid truth.

• Blake, R. A. (1977) A History of Rhodesia. London: Eyre Methuen.

• Collins, Robert o. (1990). Review: Cecil Rhodes: “Flawed Colossus” by Brian Roberts; The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power by Robert I Rotberg, in Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, pp. 336-339.

• Galbraith, John. (1974). Crown and Charter: The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press: Berkeley.

• Martin Meredith, M. (2007), Diamonds Gold and War. New York: Public Affairs.

• Oakes, Dougie. (1988). The Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story. Cape Town: The Reader’s Digest Association South Africa.

• Raftopolous, B. and Mlambo, A. S. (2009) Becoming Zimbabwe. Harare: Weaver Press.

• Rhodes, Cecil John, (1877). Confession of Faith. Available online at http://pages.uoregon.edu/kimball/Rhodes-Confession.htm[Accessed 23 March 2015].

• Rhodes, Cecil John (27 July 1894). ‘Speech to the House on the Second Reading of the Glen Grey Act’, in F. Verschoyle, (1900) Cecil Rhodes: His Political Life and Speeches, 1881-1900.South Africa:Chapman and Hall, limited, pp. 371 ”“ 390

• Rotberg, Robert I. (2002). The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. Jonathan Ball Publishers: Johannesburg and Cape Town.

• The Olive Schreiner Letters, Available at http://www.oliveschreiner.org/vre?view=personae&entry=82[Accessed 24 March 2015].

• Author Unknown, (1988) Review: Robert I. Rotberg, The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Enigma of Power, in The Wilson Quarterly, p. 138.