It’s no secret the ‘Arab Spring’ was fueled by rising food prices. And while there is a sense of calm in South Africa, the 10 percent increase in bread prices, coupled with a tense political scene, make for a landscape littered with egg shells. More so because an increase in bread prices highlights the increase in wheat prices, which is at the core of the country’s staple food. In the piece below Investec economist Brian Kantor takes a look at these price escalations and, as usual, comes to some very interesting conclusions. – Stuart Lowman

By Brian Kantor*

The Treasury has just increased the duty on imported wheat by 34%, from R911 to R1 224 per tonne. Some 60% of SA’s demands for wheat are met from abroad. Accordingly the price of bread is predicted to increase by some 10%.

This is another bitter blow for the poor of SA, some 34% of the population, according to the World Bank. One might have thought that such a step that will benefit a few farmers at the expense of a huge number of impoverished consumers of bread, makes no sense at all. But apparently the Treasury had no choice in the matter at all, being bound by an agreed automatic wheat price formula, and was forced to act when threatened by High Court action taken by Grain SA. But the responsibility for the formula is that of the government and the formula may well be adjusted in the months to come, altogether too late to relieve poverty.

And were the farmers wise to exercise their rights at a time like this? They may well end up with lower duties or better still for the economy – no duties at all on a staple most of which is imported.

In the figures below we compare in rands the global (US dollar Chicago-based price of wheat) and local prices of wheat, having converted bushels to tonnes* and dollars to rands at current exchange rates. The local price is the price quoted on SAFEX for wheat, delivered in three months. The difference in the price of wheat, global and local, is the extra that South Africans pay for their wheat, a mixture of duties and shipping costs.

SA is not self-sufficient in wheat, hence the local price of wheat takes its cue from the cost of imports. Not that self-sufficiency in food or grains is a useful goal for policy because it must mean higher prices for wheat and other staples for which the SA climate and soils are not helpful. And higher prices for staples then lead to higher wages to compensate for higher costs of living that make all producers in SA less competitive with imported alternatives. Higher prices for wheat (or rice or sugar or barley or rye) mean less land planted to maize and so higher prices for maize, in which SA is normally more than self-sufficient for all the right reasons and where local prices usually take their cue from prices on global markets, less rather than plus transport costs to world markets. The current drought in SA and its expected impact on domestic supplies, has lifted maize prices towards import price parity – another, but unavoidable, blow to consumers. Also less land now under wheat, barley or rye is given to pasture and grazing that might otherwise have held down the price of meat.

A competitive economy is one that exploits its comparative advantages to export more and import more. It does not protect some producers at the expense of all consumers, nor those producers who could hold their own in both global and domestic markets without protection. A competitive economy also will not lack the means to import food, both the basic stuff and the more exotic varieties at globally determined prices. South Africa needs more, not less, competition to help reduce poverty and stimulate faster growth. Raising barriers to trade not only harms the poor today but it also undermines their prospects of escaping poverty over the longer run.

- For more on how to convert bushels to tonnes: https://www.agric.gov.ab.ca/app19/calc/crop/bushel2tonne.jsp

- Brian Kantor is chief economist and strategist at Investec Wealth & Investment.

- The views expressed in this column are those of the author and may not necessarily represent those of Investec Wealth & Investment.

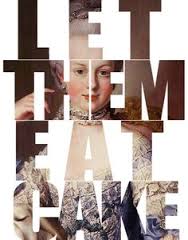

Brian Kantor: A Marie Antoinette moment – let them eat more expensive bread