If we’re serious about addressing the triple challenge of unemployment, poverty and inequality in South Africa, two of the biggest mistakes we can make are:

- To give in to scandal fatigue when it comes to reports of government corruption; and

- to believe that all (or even just the worst) corruption is practiced solely by the president and a handful of other high-ranking members of the national government.

Nothing dominates our news cycle like government corruption. Not a day goes by without several reports about irregular, unauthorised or wasteful spending, tender fraud, bribery, nepotism and a long list of other corrupt activities by various members of the government.

Keeping track of all these stories is hard enough when your job requires you to do so, but for the average member of the public it’s near impossible. One report sounds very much like the next, some of the implicated names are the same in different cases, some of the cases drag on for years and periodically reappear in our news feed. For many South Africans, the mere mention of the word “corruption” brings about a weariness that borders on apathy.

And, of course, it doesn’t help that so many perpetrators slip through the intentionally large cracks in the system. Connected cronies are connected for a reason, and our checks and balances are not always sufficient to bring them to book. So reports of corruption are often met with a helpless shrug.

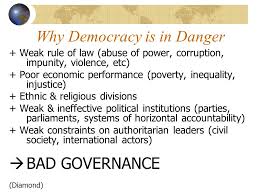

It is incredibly important that we do not become desensitised to corruption scandals because, left unchecked, corruption will be our undoing. Simply put, corruption destroys a government’s ability to fulfill its commitment to the people. It threatens the rule of law, it damages a country’s reputation and it drives away investment.

But above all, corruption steals from a country’s most vulnerable citizens. By far the biggest chunk of public resources is channelled towards delivering services and grants to poor people who are dependent on government assistance to survive. Corruption and irresponsible financial management sucks this public resource dry, and there is a direct correlation between rising levels of income inequality and growing incidences of corruption.

It is crucial that we never stop demanding honesty, efficiency and accountability from those elected to represent us, no matter how many times we hear about wrongdoings.

And the second mistake we must not make is to think of corruption as something that only happens in national government. Issues like Nkandla and the Arms Deal – along with warnings about the potential for corruption in the nuclear build programme – may get all the press, but most corrupt activities happen at local government level. And considering that this is, for most citizens, the coalface of service delivery and the only direct interaction they have with government, it is something we need to urgently address.

At this point it’s probably worth taking a look at what is meant by corruption. Broadly defined, it is any abuse of public resources or power for personal gain. This typically happens across all levels of government, and across all departments. And when we say “resources”, we’re not just talking about money. It could be things like vehicles, property and travel allowances too. Corruption could take the form of a bribe to secure a contract, obtain a licence or avoid a penalty, it could be abuse of a government-owned car or it could be nepotism.

In fact, we have found it is the latter – unbridled nepotism in municipalities – that has come to symbolise corruption for many ordinary South Africans. Being constantly overlooked for a job simply because you don’t have the right connections has a direct impact on your life and really drives home the “economic insider vs outsider” aspect of corruption.

In July 2013, a report by Transparency International found that 47% of South Africans who had dealings with government officials had paid a bribe to officials in the previous year. That’s a staggering statistic.

Of course, there is a case to be made that the same people (or type of person) who exploited the corruptibility of the Apartheid-era government are now doing the same with the African National Congress government. But simply being no worse than the Apartheid government is just not good enough. And it is certainly no justification for entering politics to become a “crony capitalist”.

Tackling corruption requires a lot of commitment. It requires functioning investigative and prosecuting institutions and it requires a very disciplined tightening of financial management. It is not something you can do with platitudes in annual state-of-the-nation addresses, as our president seems to think.

And President Jacob Zuma is not alone in offering empty promises of graft-busting steps. We’ve heard the exact same rhetoric about “introducing measures to fight corruption” from, amongst others, Ace Magashule, the controversial premier of the corruption-ridden Free State. But given both Zuma and Magashule’s personal track records, and the thick cloud of corruption allegations hanging over both of them, these promises mean nothing.

Announcing intentions to fight graft is not the same as actually fighting it.

In the Democratic Alliance-run Western Cape, the benefits of a zero-tolerance approach to corruption are there for all to see. Government officials in the province are prevented from doing business with the state, tender processes are transparent and are open to public scrutiny, and the province’s excellent performance in the recently released auditor-general’s report (all 13 provincial government departments received unqualified audit results, and 12 received clean audits) is testament to a well-run government. It is no coincidence that this is also the province with the highest access to basic services in the country.

If we are to stop corruption and waste, we need the national government to apply the same disciplined control over our public resources. Specifically, the disciplinary and criminal procedures laid out in the Public Finance Management Act must be adhered to so that authorities are held to account for unauthorised, irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure.

It is also crucial that we waste no further time in adopting the long-overdue Supply Chain Management Bill as well as inducting a central supplier database, which will go a long way towards addressing corruption in the procurement of goods and services in all three levels of government.

We must also stop appointing people to crucial roles in government, state-owned enterprises and the various institutions of our democracy based solely on their loyalty to a particular figure or faction. Where cadre deployment thrives, corruption inevitably also thrives.

And finally, we must expose the 200,000 government officials who currently transact with the state.

We cannot let the scourge of corruption deny millions of South Africans the opportunity to get ahead in life. With a little political will and a lot of hard work, we can tighten our financial management and turn the screws on corrupt officials.

This will mean more services, more grants, more houses, better healthcare and better education – in short, a better future for all South Africans built on the values of freedom, fairness and opportunity. DM