16 December 2013

Today, on a Sunday 175 years ago an event began which changed the history of South Africa. In a roundabout way, it was an event that changed the history of the world. It was the start of perhaps the most dramatic event in the blood-stained pages of our country’s past. And it was the start of a day that may never be forgotten as long as blood flows through the veins of the Afrikaner nation.

The story of what happened was told to me by Uncle Gert de Jager – and he repeated it for me a few months before his death at the age of 92. I asked him to tell it to me slowly so that I could listen with care and make sure that I understand it correctly. He even wrote down what he could remember, to make sure that it would not be misunderstood. These were facts that he still heard personally from his father and from his great-grandfather who had been present at the time. Several of my other family members were there also. Some of the events that I am about to tell of are poorly known. But this, to the tribute of those who were there – and to the glory of the Hand which protected them, is the story of what took place:

Uncle Gert’s great-grandfather remembered that when night fell upon the velvet green landscape of Natal, it was dark moon, as we call it. The night was so black that you could not see your hand in front of your eyes. In the western sky the lightning flickered on and off. The night ahead looked ominous, but so did the months that lay behind them. With one or two exceptions, it had been a series of never-ending disasters. There had been the Liebenberg murders during which unsuspecting pioneer families were suddenly overwhelmed and cut to pieces. Then there had been the climactic battle of Vegkop during which only 37 men, servants and boys fought off 4,000 Matabeles. There had also been the months of being besieged in rain-drenched laagers during which time they suffered dreadful hunger and disease. There had also been the tragic scene in which the Trek leader Piet Uys was led into an ambush, where he and his young son were brutally slain. It was an incident that had left the pioneers divided and weak.

Furthermore, there had been the worst day of all: the day in February of that same year when their leader, Governor Piet Retief was murdered, along with his young boy and his entire party of men. They had just concluded a successful land purchasing transaction with Dingane, king of the Zulu. During the festivities that followed, Dingane suddenly rose and shouted: “Kill the witchdoctors!” upon which Retief and all his unarmed men were seized. Their fate was so horrible that it cannot be described without shocking the senses. They were impaled alive and fed to the vultures – with Piet Retief being forced to watch it all until he too, as murdered.

That same night, the Zulu impies had swept across the length of the upper Tugela river. They fell upon the unsuspecting encampments of families across a huge distance. It was totally unexpected. In the darkness, that evening became the sum of all nightmares as unspeakable cruelties were committed. While men fought desperately in the darkness against an unseen foe, they were overcome by sheer force of numbers. Pregnant women were cut open, and children and babies were swung by their feet to have their brains bashed in against the wagon wheels. In that one night 500 men, women, children and servants were butchered. Their bloodied bodies with drawn-out entrails were found among the charred remains of their burnt out tents and wagons the next day. It was a crime and a tragedy in that small community which was so great that words could not be found to express emotions.

After this incident the pioneers realized that they were now faced with most desperate hour in the entire existence of civilization in Africa south of the equator. All attempts at peaceful relocation had failed. Their honest intentions had been met with murderous deceit. And now they were left weakened and vulnerable in a strange and hostile land.

Dingane commanded the most fearsome army in the history of Africa south of the Sahara. For two generations they had swept the southern and central parts of southern Africa, killing and murdering as far as they went. Entire nations were driven to the brink of extinction. In the Mfecane, or great cleansing, the vast interior had in fact become uninhabited by humans, except for a few miserable starving souls who tried to survive in the isolated mountain regions. They were already driven to the extremes of cannibalism as a result of these deprivations.

The pioneers knew that they had only two choices – either to return to the Cape Colony where they had already been exposed to nearly 60 years of border warfare – or to act with daring defiance that might amount to suicide. They knew their resources were desperately weakened by that time. But they had never been weak as men. And so they chose the most bold and daring action of all – to attack in order to survive. They knew the risks. It would be an all or nothing act of the most desperate kind. There would be no partial victory. It would be total victory or total oblivion. There was no doubt about the gravity of the risks they would be facing.

Accordingly, when the spring rains came, a fighting force was assembled. The pioneers had no army. They were simply farmers, sons, fathers and grandfathers who had to defend heir families with every fibre of their strength. Even so, only 470 men could be assembled. With them came their 150 strong service core of ex-slaves and servants who would not be there to fight, but only to handle the livestock and move supplies.

When their reconnaissance-men returned, the news was dreadful to the extreme. The armies of Zululand were on the move. Like rivers of dark ants the dreaded regiments of the amaZulu – literally “people of the heavens” – were already streaming through the valleys towards them. They knew that battle had become unavoidable, and the best they could do was to hurriedly find a place where they could wait for it.

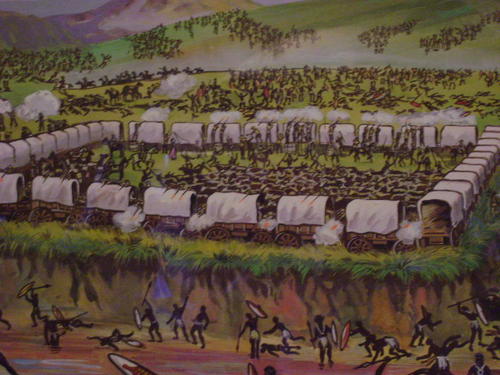

The place they found was on what would become Uncle Gert’s family’s farm until the current generation. There the desperate pioneers drew their wagons into a circular shape. On one side they had a deep ravine and on the other side a flooded river. In the space between these two defences there was only open range – a soft green landscape of rippling grass that afforded clear views northwards. This would be the theatre of death on which they had to act out the most terrifying play of all. In great haste they lashed the wagons together. The gaps between them were closed off by wooden grates, called “fighting gates.” Ammunition was checked, guns were oiled, and then they settled down to wait. If their spies were right, the Zulus would not keep them waiting long.

The men who were there that day must have known that on this fateful night they had come to fight back – or be exterminated from history. There would be no middle ground. They tough men, but ordinary all the same. Old men with weathered faces and gnarled hands. Middle-aged men who thought about their wives and unborn children. And clean-faced youths who had not experienced very much of battle yet. The Voortrekkers knew that theirs was a precarious situation. They were hugely outnumbered. Surrounding them in the darkness of an African night was possibly the biggest army that the Zulu empire had ever assembled. They were the most experienced, most cruel, and most effective army in Africa. And they were there to kill to the last man.

The Zulu army was exceedingly great. But they were pitched against an enemy who knew where their strength lay. Knowing that humanly they had no hope at all, the pioneers had made a covenant with God during the preceding days. A covenant which they had repeatedly every night. And a covenant which successive generations have continued to renew ever since that day. In this covenant, they had promised to God that if He would grant them victory, they would build a church to His honour, and that they and their descendants would honour this day as a Sabbath in all perpetuity. The pioneers had no ministers of religion with them, for not a single one had been willing to join their exodus. But that did not mean that they did not have some men of faith to lead them. Sarel Cilliers was a man who carried the word of God like a sword. And they called upon his to lay their case before the Lord.

Gathered round their spokesman, where he was standing on a small ship’s cannon, they renewed their covenant for the last time. His words must have sounded grave and hollow in the suffocating mist as he made his famous deal with God and spoke words that have been echoing across the ages ever since:

“At this moment we stand before the Holy God of heaven and earth,

to make a promise if He will be with us and protect us,

and deliver the enemy into our hands so that we may triumph over him,

that we shall observe the day and the date as an anniversary in each year,

and a day of thanksgiving like the Sabbath,

in His honour,

and that we shall enjoin our children that they must take part with us in this for a remembrance even for our posterity.”

When it was over, cold fingers returned their damp hats to their heads. Hauntingly, their sad and melancholy psalms filled the night. And then the long sleepless wait began. Trouble was all around them. They knew it from the barking of the dogs, and from the restless way the cattle and horses milled around. Lantern light shines barely five paces. Beyond that the grass was rustling. That, they all knew, was the sound of death.

On the Zulu side, it proved to be a night like no other. The army had planned to attack the laager at midnight. Had they done so, it would have been a massacre. But this did not happen, because everything started to go wrong in dreadful slow-motion fashion. From nowhere an eerie mist settled in – a mist that was so thick that it enclosed the whole landscape and swallowed the Zulu army. The Zulu regiments got hopelessly lost, and after marching twice around the wrong hill, they concluded that the white men had managed to make themselves invisible by means of powerful sorcery.

The regiments who did manage to find the laager were baffled by what they saw. The Voortrekkers had tied lanterns to their whip sticks, which they then suspended above the wagons. In the haunting fog the diffused light of the lanterns looked like suspended balls of fire, and so the mightiest nation in Africa paused to reflect with superstitious awe. By slowly following the trail of the wagons the main force finally found the laager near the end of night. When most of them had reached the spot, they sat down on their shields and prepared to wait. Some were testing the sharpness of their spears already. Spears that had already tasted an ocean innocent blood.

Dawn broke with milky whiteness which yielded unwillingly before the eastern sun. In the laager the men had barely closed an eye. By the low droning of thousands of voices they could tell that they were completely surrounded. In the laager their horses and cattle were milling fearfully. Even they could smell the danger. After a while they were able to faintly make out the figures. The nearest ones were seated 50 paces away. In their hands they carried the long throwing spears of their ancestors, and the short stabbing spears of Chaka. In their hearts they bore the wish of death. Beyond them the regiments were still arriving like angry ants across the landscape. The pioneers could not believe their eyes. There were thousands upon thousands of them. So many that not even the Zulu commanders could count them. As many as 30,000 warriors were assembled, some history books say. Uncle Gert’s grandfather held that after both calculation and from his impression as a whole, the number might have been far larger yet. The odds were at least 63 to 1 – if they were lucky.

Inside the laager the Voortrekkers were deeply concerned. They knew almost without a shadow of doubt that they were doomed. Not only because of she sheer numbers against them, but particularly because they knew that after a night of such heavy fog their gunpowder would be rendered entirely useless. Gunpowder had a famous affinity for moisture. And after such a foggy night, the men all knew that their guns would not be firing. With a sinking feeling they realized that at this point nothing but a miracle could save them.

What they did not know was that his was destined to become a day of miracles. While they were still vainly straining to peer into the mist, it suddenly lifted. One moment it was there, and the next it just rose and vanished away into thin blue air. The change was startling and completely unexpected. Uncle Gert’s grandfather stressed that this was unprecedented and unbelievably dramatic. Suddenly not even a single cloud remained. Now, beneath the harsh glare of the morning sun, they could see that they were completely enclosed. With a surging drone the regiments rose. Lines upon lines of dark figures, grandly arrayed battle dress: plumes around the arms, blue crane feathers in the hair to signify war – and different coloured shields to identify the individual regiments. In their hands they held the sharpest spears in Zululand. And they were ready for the kill.

They wasted little time. At the blowing of a reed trumped the mass of straining warriors leapt forward, bellowing the ancient blood-curdling battle cry of “Usutu! Usutu! Usutu!” Thousands of spears were beaten against thousands of shields so that the very air shook with the thunder of it. It was as if the whole landscape had turned into a black avalanche which came thundering towards the dim square of fragile wagons. The attack was swift and brutal. With great anxiety the Voortrekkers held their fire – and then pressed the triggers. To their utter astonishment the powder exploded in all guns – and the laager erupted into a wall of liquid fire, followed by an avalanche of pure white smoke. In each barrel the men had placed multiple balls of lead. And now they were firing for their very lives. There was no need to aim. At each shot several warriors fell to a single shot – with great holes blown through their bodies by the heavy lead balls. Some tried to catch the bullets with their hands. Others charged forward without fear – for they had been blessed by their witchdoctors at their departure – and many believed they were untouchable by death. Yet, death found them faster than the speed of sound. And Uncle Gert’s great-grandfather said that they fell across each other like a reed patch in the wind.

In the laager, the men staggered back to reload their muskets with trembling hands. It took 2-3 minutes to reload each gun, and it must have taken about that long for the first warriors to reach their position. Yet the strangeness continued. After the third volley the smoke was so dense that the whole army could no longer be seen. Perplexingly, however, moments later the gun smoke cleared again – rising straight up into the air. This too, was something the defenders had never encountered before. The pride of Zululand broke as their front ranks faltered. And then the commanders began to think. Hurriedly the signal was given so that the warriors withdrew to beyond gunshot and settled down to reflect. The battle had started badly.

Realizing that they had to take advantage of momentary confusion, and emboldened by events thus far, Uncle Gert’s grandfather, along with some settlers then galloped out to provoke a new attack. In this they were successful. With a fearsome cry the battle-tested warriors leapt to their feet and came for them. With the sound of many waters their limbs raced across the bloody fields. Shouting and leaping across their fallen comrades they came – bellowing with rage and determination. Yet they ran into a wall of death again. Slight though the effect was upon their huge number, it nevertheless caused them to slow the attack.

When the second assault finally also faltered, 12 mounted men were sent out to provoke the next wave. As dreadful as it seemed, the regiments had to be kept moving so that they would not be able to rest. They were not as quick to respond this time. Then one man, Flip Coetzer, shouted at them.

“This time it’s not the women and children that you murdered in the camps,” he shouted at them, “but strong men who came to vanquish you!”

The next attack came at once. With earth-shaking thunder the regiments ran into streams of screaming lead. In the laager the small ships’ cannons thundered methodically. Their ranks crumpled like wheat before a scythe, but their numbers seemed limitless and they were advancing faster than the few hands could reload their cumbersome flintlocks guns. Even the three small ships cannons were unable to blow large enough holes into their ranks. It was as if all of Zululand had been unleashed upon the tiny circle, and for a moment it must have seemed as if they were about to be engulfed. And yet, again the attack lost impetus and then turned into a soft retreat.

At this point the Zulu commanders decided that there was no need for further attack. With their superior numbers all they needed to do was draw the circle tight and besiege the settlers. That night, they argued, they would close in and wipe them all out cleanly. At night settler eyes could not see to take aim. At night they could simply swamp the brittle defences and slaughter every living soul inside.

But suddenly a strange problem arose. The young warriors were still bloodthirsty and rearing for battle. They were severely dissatisfied at being denied more opportunity to attack. Furthermore, a few of them had made a new and critically-important important observation. It had quietly occurred to them that every time the horsemen were sent out, it took some time for the wagon that served as a gate to be drawn back into the perimeter. And during that time the entire defence was deeply vulnerable. Some of them had therefore devised the plan of sneaking around towards the gate area. When the horsemen were let loose, they planned to rush inside before the gate could close – and once that happened the battle would be over. From inside the settlers would stand no chance at all. Thereupon, a great argument ensured among the leaders, but eventually it was decided that this would be the surest way to victory. And so the young men stealthily moved into place to execute their plan.

Exactly as expected, the settlers soon sent out another 18 men to charge at the enemy and fire into their ranks. The young men saw the gate open and recognized their chance. This was when they would all be heroes – and they rose with whitened knuckles around their deadly spears. What followed next should been a race to victory. But then the strangest event took place – something that history could never explain – an event which some would later point to as having been one of the greatest miracles in our nation’s history.

“Even though each of us directed our gun shot at the nearest Zulus,” Uncle Gert’s great-grandfather remembered, “their faces were not directed at us. In stead, they were facing the mountain, in which direction they beckoned to each other.”

When this happened the curious horsemen blinked with astonishment. They could not believe their eyes when, almost as if by a prearranged signal, much of the entire Zulu army turned and ran. But not all of them, as Uncle Gert explained. Flight was not permitted in the Zulu army, and so the older regiment of white shields would not let the young ones depart. Running into their path of retreat they presented steel – and the two sides clashed with a thundering report. Before the incredible eyes of the settlers the Zulu army began slaughtering itself with the most bitter passion.

There are no words to describe the utter rout that now took place. The slaughter was so intense that many fell down and pretended to be dead. Suddenly it had become a fight of brother-against-brother and father-against-son. The pride of Zululand was cutting itself to pieces in a way that nobody had ever seen before. The scale of the confusion was beyond description. Many just ran in any direction – and the direction that most were drawn to was the direction that lead home. Accordingly, an enormous number of them plunged into the Buffalo river where they were drowned or swept away, or presumably taken by crocodiles. It was an outcome such as no man had ever expected to see.

As the battle of screaming humanity thundered away from the powder-stained laager, the Voortrekkers stared with disbelief. How could such a thing be possible?

The 18 men, in particular, were dumbfounded. They must have looked towards the mountain behind them many times and blinked in complete astonishment. What did the Zulu army see which had instilled the terror of death into their hearts? They looked, but they could see nothing. They were speechless.

The answer to this mystery was only revealed years later when old survivors of the battle came to Uncle Gert’s family and told them their version of the story. I had heard this story since I was a little boy, but this time I quizzed Uncle Gert most carefully. I wanted to make sure that I got the story exactly straight.

Uncle Gert told me that the old survivors told his father and grandfather that the turning point came when they looked up at the mountain and saw the most perplexing sight. According to them they saw a mighty army of fighters on white horses and streaming banners, tearing towards them across the soft green landscape. It was an army of cavalrymen, they said. And leading them – right at the very head of their columns, was a single man upon a white horse that carried a long knife – which was their way of describing a sword. It was at this dramatic appearance that the young regiments turned and fled.

As for the veteran regiments and even the settlers themselves – they never saw a thing. Not one of them saw that phantom army. The thought never even crossed their minds. Yet this story was told to several members of Uncle Gert’s family on various occasions. They shared what they heard with their friends and neighbours, but as Uncle Gert told me, most of them just dismissed it as “Zulu stories.” They themselves had, after all, never seen the white army.

In the meantime, the settlers pursued the fleeing Zulus. All around the laager the fight continued in places. Here and there it turned to hand-to-hand combat. Both Voortrekker leader Karel Landman and Andries Pretorius were attacked by Zulu warriors and both succeeded in killing the warriors with their own spears. Pretorius was wounded in his hand in the process. He was 39 year old at the time.

Uncle Gert told me that the settlers rode up and down the river banks for several hours – firing at all the noses they could see – and defending themselves from periodic attacks from the reed beds. Between the regiments’ killing themselves and the Voortrekkers’ shooting at what they could see, the river slowly turned red with the blood of Zululand’s best. And that is where the river got the name by which it is know to this very day: Blood River.

The Battle of Blood River was the pivotal event in South African history. After Blood River the Zulu army was still mighty. But after decades of slaughtering hundreds of thousands of innocent black tribesmen across South Africa they never managed to reorganize themselves completely. It was as if the fright that had taken hold of their hearts on that day remained with them forever. King Dingane was so shaken by the defeat of his enormous army that he burnt his own capital at Ulundi and fled into the depths of Zululand where he felt more safe. For the time being, this left him unwilling or unable to reorganize his armies.

During this time of confusion the Voortrekkers took possession of the land of Natal which they had fairly bought from the Zulu king months ago. A year after their deputation had been treacherously murdered by the Zulu king they discovered the skeletons of their fallen governor with the deed of sale still in his leather pouch. It exists to this day, still bearing the cross which Dingane had scrawled upon it by his own hand. Dingane had murdered Retief’s men, but he had already set in motion a sequence of events that could not be altered. After this the land was safe to dwell in.

In the annals of famous South African battles, none are as important or as famous as Blood River. It was the most unlikely of victories under the strangest of circumstances. There are those who may ascribe the deliverance to luck and pluck. Some scholars and armchair historians even argue that the outcome had been assured because after all – what match coul spear-carrying natives have been against modern firearms? And yet, if one carefully thinks about it, the argument seems pitifully flawed. When the overwhelming force of numbers is considered, the entire notion becomes childish.

There are many who will always acknowledge that “something took place” that day at Blood River. Something that was not of human making.

Among the settlers, only two were lightly wounded, one of them being the commander himself. Among their ranks, not a single man was killed. Among the Zulus the number of dead as so great that it could never be estimated. According to Uncle Gert, his great-grandfather said that in his opinion the numbers must have been close to the largest figure that history suggests. A figure so great that it is often regarded as improbable. The dead numbered in the thousands – and the greatest part of these, Ungle Gert’s grandfather said – did not die by settler bullets. They were killed by the blades that had been forged in their own kraals. Whatever the real facts, it was a totally unlikely outcome of incredible significance.

This day continues to be remembered for divine deliverance in a battle which the settlers never could have won on their own. The covenant that was made on this day was renewed many times by succeeding generations. There are those who choose to dismiss the covenant, or the events which took place on that day. But there are some who still remember. And some who still acknowledge that we are alive today because that ancient battle had been won. Without it, the history of South Africa would have been vastly different.

In 1938 my great-grandfather wrote a letter to his son, whose name I bear. It was the year of the centenary of the Great Trek. That letter was carried by one of the centenary wagons which trekked all the way from the Cape to Pretoria where the Voortrekker monument was revealed on this same day. It was a letter that he had written not only for his son, but also for posterity. He ended his letter with the following words:

“And so we close with the prayer that this Centenary would contribute towards making of us better, father, mothers, better sons and daughters, better Christians, better burghers and fatherlanders. And that the heritage of our forefathers would always be held in great honour, that it shall be built up and improved, and that we may become a noble nation in a pure land. That you, dear Herman, with everyone entrusted to you, would have a happy and a blessed future in our beloved South Africa – this is the blessing and prayer of your loving parents.

In my family, we have never had any doubt at all that God’s hand was to be seen at Blood River. We have been reared with a sense of ever-lasting gratitude that victory had been granted to our forefathers when they certainly could not have deserved it.

I visited the 175th commemoration of this Battle of Blood River and the Great Trek at Hartenbos today. With me there were the descendants of many of the men who fought that day – and across South Africa – their number is beyond estimation. At the commemoration Frans Moolman, professor of history, said something that made a significant impression on me. He said that the Battle of Blood River has been politicized so much. It has been dismissed as irrelevant by modern generations. It is often even held in a negative light from the point of racial relations. And yet, he argued, if this is how the world is viewing it, they are missing the entire point.

The facts of history show that the Battle of Blood River was not the result of land-hungry invaders that had come to disturb a peaceful people. In stead, it was a peaceful people who had come not to rob land, but to fairly purchase it. When they were faced with murderous treachery, they presented arms out of a sense of self-preservation. That they survived, could only be accounted to divine intervention. The Battle of Blood River, he pointed out, pointed not to the triumph of white over black. In stead, it marked the triumph of the light of civilization over the cruelty and barbarism.

I never really thought about it like that before. Professor Moolman said if the tribes of South Africa understood Blood River for what it really was, they too, would commemorate the day with much enthusiasm. After all, between Chaka and Dingane, innocent thousands without number had been slaughtered. Death, superstition and fear pervaded that land from the dry interior to the shining coast. When the might of the Zulu nation was crushed at Blood River, that was when the bell of liberty rang for the multitudes who would surely still have perished beneath Dingane’s cruel hand.

As for king Dingane, he died as he had lived – assassinated as a back-stabbing traitor, just the way that he himself had assassinated his own half-brother Chaka before. His successor, Mpanda, remained a loyal friend of the Andries Pretorius, the victor of Blood River. Between the two they signed a treaty of “everlasting friendship.”

The Voortrekkers never lost their respect for the Zulu nation after that, nor did the Zulus lose their respect for the Trekkers. I grew up with the Zulus – and always felt that in the greater scheme of South African politics, there exists a strangely respectful bond between our two peoples. Perhaps not a bond of total brotherliness, but the bond of understanding that can be found between two groups who would like to never go to war against each other again. In my family, I never knew a shred of disrespect or resentment about those dreadful times of the past.

Finally then, we can look at Blood River today and ask ourselves what would have happened if the pioneers had lost the fight that day? Almost without question, the Zulu armies would have spilled across the land and slaughtered all the encampments in Natal. From there they probably would have wiped out the settlements in the deep interior. What they did not finish off, the Matabele of the north probably would have taken care of.

Inspired by these successes, it is likely that the Xhosa of the Eastern Cape would have launched the greatest assault against the eastern border. Desperately weakened by the departure of the pioneers of the frontier, the Colony very likely might have collapsed. It is not unthinkable that it might have wiped out the light of civilization in South Africa for the next half a century or more. If this had happened, the history of the world would have been entirely different. Throughout all of this, genocide would have followed genocide among the black and brown races of the southern continent – and millions who are alive today would have never existed.

This then, sums up the history and the significance of the most important day on the calendar of South Africa. This is a day that our children should know of – and that the world should understand. In the end victory came to the pioneers not because they were good, but simply because God was great.

May we who live today, never forget to teach that to the heroes of tomorrow.

http://www.labuschagne.info/the-miracle-of-blood-river.htm#.VLuy3keUd8E