This episode of NOW with Bill Moyers brought a story of unspeakable tragedy and a painful search for justice. It introduced Mary, a young girl in South Africa who was raped repeatedly by her step-father and infected with HIV as a result. And she wasn’t alone — tens of thousands of young girls have been attacked in their homes and on the streets, often by men who believed sex with a virgin can cure AIDS. The horror was only made worse by a South African government that witheld the drugs that could save these young lives.

Journalist Jamila Paksima traveled to South Africa to look for answers. And Archbishop Desmond Tutu, recipient of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize, talked to Bill Moyers about the desperate situation in South Africa: “I have said that we are facing a kind of new apartheid, and that we had a particular kind of commitment in the struggle against apartheid. And I’ve said, let’s invoke that same spirit in face of this massive, massive challenge.” You can access the original Web page for this program at the archived NOW with Bill Moyers website.

TRANSCRIPT

BILL MOYERS: Welcome to NOW. This week, we bring you a story of unspeakable tragedy and a painful search for justice.

You’ll meet a young girl in South Africa named Mary. She was raped repeatedly by her stepfather and infected with HIV as a result. And Mary’s not alone.

There’s an epidemic of rape in South Africa, and tens of thousands of young girls like her have been attacked in their homes or on the streets. The horror is made worse by a South African government that withholds the drugs that could save these young lives.

Video journalist Jamila Paksima went to South Africa as a Pew Foundation Fellow in international journalism, and found behavior there more disturbing than anything she could have imagined.

JAMILA PAKSIMA: These are some of the girls I met in South Africa.

Rachel (SINGING): I want to go to heaven in the morning.

PAKSIMA: Her name is Rachel. In Sotho, it means “happy.”

This is Mary, she has dreams that wake her up at night.

Mpumi and her twin sister Nompumelelo love to sing in their church choir.

They all share a terrible experience: they have been raped, including Thandiwe, who is two. Today this teddy bear is her only comfort.

In South Africa, one in five people between the ages of 15 and 49 is HIV-positive. This means many rape victims face a long and painful death sentence.

DR. YAKESH BALDEO: Nobody seems to want to admit that we have a serious problem.

PAKSIMA: Dr. Yakesh Baldeo oversees the crisis center in the state hospital near Durban. He practices in a country which has one of the highest rates of HIV And rape.

BALDEO: We have exceeded over 200 cases a month. That’s roughly about six cases a day

PAKSIMA: Two hundred rapes a month treated in this one hospital alone, and nearly half the victims are young girls.

BALDEO: Nine years. Three years. 13 years. Seven years. Those are children.

It’s a big crisis, and it is all linked: rape, HIV, it’s not working. One needs to really find a solution.

PAKSIMA: No one has found that solution. They keep looking.

This is greater Nelspruit, 220 miles from Johannesburg.

Fakile Sibiya is a community worker. She is taking me to meet a little girl named Mary.

Mary’s friend says she’s not home from school yet. Coming home can be dangerous. Most rapists are not strangers. They are relatives, neighbors and sometimes gangs of boys.

Fakile is warning the children a group of men nearby have been drinking. The girls are not safe on the streets. And they are not always safe in their own families.

FAKILE: There’s Mary.

PAKSIMA: She is escorted by her aunt. Mary is too frightened to walk alone.

Fakile translates for Mary.

MARY (TRANSLATED): My father came to me and he jumped over from the bed and he came to me. He just blocked my mouth and he raped me. He told her that if she told someone, he will kill her.

PAKSIMA: Mary, her grandmother, aunt, and cousin were willing to talk about what happened. It wasn’t easy for them. The rapes went on for weeks.

MARY (TRANSLATED): It was on Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday.

PAKSIMA: Every day?

In the same room where she sleeps on the floor, it would happen, most often late at night. Mary says her stepfather would leave his bed and force himself on her. Her mother slept through it all.

FIKELE: She feels bad on her vagina, and she decided to tell her mother.

PAKSIMA: Her mother’s name is Linha. Mary told her mother in front of the father. He then beat Linha up.

LINHA AND FIKELE (TRANSLATED): The first thing that came in her mind was, go to the police station and report the matter.

PAKSIMA: Like so many, Linha and Mary are poor. It was a bold step to come forward after two months of abuse, to turn in the family bread winner.

The police took them to the hospital where Mary and her mother were given blood tests. The results were a crushing blow. The husband, Mary’s stepfather, had infected them both with HIV. Linha doesn’t want Mary to know.

FIKELE: Her daughter is always asking her mother that she is HIV-positive, both of them. And she is always telling her that it is not true.

PAKSIMA: Mary had waited too long before telling her mother, and lost her only chance for help.

BARBARA KENYON: Her name is Mary, and we’ve tested her and she’s HIV-positive.

PAKSIMA: Barbara Kenyon has founded GRIP, a rape assistance program in Greater Nelpruit. She is raising money to help rape victims like Mary.

KENYON: I don’t know whether I am crying for what she looks like now. And I don’t know whether I’m crying because I know where she’ll be in two years time — emaciated, and in pain, covered in mouth sores, and everything like that.

This month is bad, it’s bad. There’s all these little two- year-olds. These are the victims, ages ten, one, nine, three, six, three, 11, 13, three. Oh, it’s just horrific.

And it’s just getting worse. It is just getting worse.

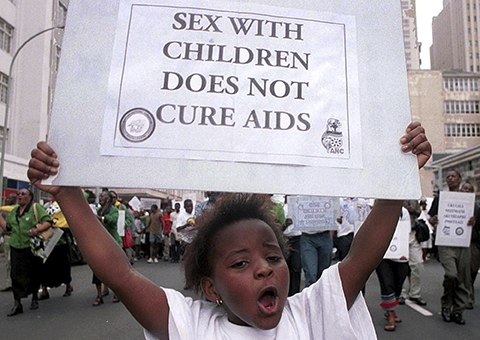

PAKSIMA: Some people say it is getting worse because of South Africa’s faith healers, the sangomas. They are blamed for spreading a belief that sex with a virgin will cure HIV.

SANGOMAS: If that people is HIV-positive, we can try to help him.

But if it’s AIDS, we can’t help him, that thing gets in his body, it’s difficult, it’s difficult.

DR. BALDEO: Most of these rapes are the result of HIV-positive men assuming that they can become HIV-negative if they slept with a virgin.

PAKSIMA: It has become so controversial and so widespread, it’s simply known as “the myth.”

(MOTHER OF A RAPE SURVIVOR): They tell them that, if you sleep with a virgin, especially a young child, it has to be a young child, then you can be cured, because the blood is fresh.

They say the blood is fresh and it’s sort of, like, holy; then it can cure you.

LISA VETTEN: It is a very old myth, and it’s certainly not unique to this country.

PAKSIMA: Lisa Vetten works for the Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.

LISA VETTEN: If one looks at Europe in the last century, when venereal diseases, syphilis, and gonorrhea were incurable and led to people’s deaths, exactly the same belief was circulating then, and it appears to resurface whenever there are these medical epidemics of life-threatening illnesses, where there is this is confluence of sex and death.

PAKSIMA: To cope with this crisis, the government has mounted education campaigns and a nationwide push to offer free condoms.

It isn’t working.

PAKSIMA: More than half of Barbara Kenyon’s clients are children. She works with local volunteers to locate survivors and follow their HIV status. Most of the organization’s energy and money is being spent on these.

DOCTOR ON PHONE: Two of them three times a day.

PAKSIMA: Anti-retrovirals.

DR. BALDEO: There is no doubt it is beneficial to rape survivors and to anyone who is actually HIV-positive.

PAKSIMA: There is no cure for HIV.

The medication suppresses and can even prevents HIV infection, but it must be taken within 72 hours after a rape.

That’s hard to accomplish when resources and transportation are limited and government stands in the way.

KENYON ON PHONE: Oh, it makes me so angry, the bloody government.

That child should be able to get that medicine.

PAKSIMA: The President, Thabo Mbeki, questions the facts: whether HIV causes aids, whether his nation is even facing a crisis.

PRESIDENT MBEKI (EXCEPT FROM SPEECH): You see, when you ask the question: Does HIV cause AIDS? The question is, Does a virus cause a syndrome?

How does a virus cause a syndrome? It can’t.

DR. MOLLY SMIT: I mean, somebody says there’s a virus and somebody who you respect— like your president— says they’re not sure it’s a virus.

And you don’t have much scientific background, and you’re not educated, what do you believe?

PAKSIMA: The President also says anti-retrovirals are toxic. His parliament refuses to distribute them in state hospitals.

DR. BALDEO: We actually do not have any authority to issue anti-retroviral treatment to rape survivors. We are not allowed to prescribe it because of the government’s policy on the drug at the present moment.

PAKSIMA: The ban only extends to government hospitals. But if you have money, you can get the medication through a private doctor or through insurance. But it is costly, as much as two months salary. Most South Africans are poor and have to rely on state hospitals and doctors.

KENYON: Did she get the medicine?

PAKSIMA: So organizations, like Kenyon’s, use legal loopholes to get the anti-retrovirals to rape survivors. She turns to sympathetic doctors in private practice.

DR. BONGANI TWALA: People are sick and tired of this. People cannot take it anymore.

PAKSIMA: Dr. Bongani Twala is one of many physicians who offer consultations and write prescriptions for Kenyon’s clients. Her rape assistance program picks up the tab for the medicine.

TWALA: They use this medication for the first three days within 72 hours.

PAKSIMA: Is this what they call the starter pack?

TWALA: This is the starter pack, yes.

PAKSIMA: This guerilla health war has provoked a political confrontation.

KENYON READING FROM NEWSPAPER: “Hospital counselors who are trying to distribute anti-retrovirals to rape survivors are trying to overthrow the government.”

GRIP WORKER: And what you are wanting to do is help people.

KENYON: I know, I break my neck to help them.

PAKSIMA: The government is even suing to kick Kenyon’s program out of state hospitals.

But the crimes keep happening, and the perpetrators are getting younger.

Every boy in this offender program raped someone. Their ages are between 14 and 17. They agreed to talk as long as I didn’t identify them.

FOURTEEN-YEAR-OLD BOY: My friend’s, his uncle told us, “if you have AIDS and you sleep with a small child or a virgin, you won’t have it anymore.”

I don’t believe it. I don’t think it is true.

PAKSIMA: This boy was 14 when he raped his neighbor.

FOURTEEN-YEAR-OLD BOY: I hadn’t has sex for some time.

PAKSIMA: The child was five.

FOURTEEN-YEAR-OLD BOY: I was practicing on the child what I would do to my girlfriend.

PAKSIMA: During my stay in South Africa, a series of incidents so outrageous forced the public to finally take notice: a spate of infant rapes. These men were all charged with the rape of a nine-month-old. This five-month-old survived her attack.

WINNIE MANDELA (FROM TAPED SPEECH): This is an indictment to our society. It is an indictment to our country. What is it that we have not done?

PAKSIMA: One South African after another told me it is getting harder to believe in justice.

LINEO: This is a serious case.

PAKSIMA: Courts are overburdened and only have a seven percent conviction rate for rapes. Investigations often go nowhere.

COUNSELOR IN SCHOOL: At that time you’ll be feeling dirty, feeling awful, scared.

PAKSIMA: So young children are being taught how to collect DNA evidence if they are raped.

COUNSELOR IN SCHOOL: Most important thing, never, never wash your panty, okay? When you are sodomized, never wash your underpants.

PAKSIMA: Other kids are being prepared to go to trial and testify against their attackers.

Rachel: I was crying and I was screaming, but no one heard me.

PAKSIMA: Like nine-year-old Rachel at the Teddy Bear Clinic.

SOCIAL WORKER: There’s a happy face and there’s a sad face and there’s a scared face. Which one are you feeling? There’s a scared face. So which one are you feeling? Which one are you?

RACHEL: I’m feeling scared.

SOCIAL WORKER: You’re feeling scared.

PAKSIMA: In the last year, Rachel was gang-raped by five boys and by her 22-year-old cousin.

She is too young for gray hair, too young for many worries.

SOCIAL WORKER: If it doesn’t worry you, put it in a small cup, okay. And then, if worries you a little bit, put it here. And if it worries you a lot, you put it in this cup.

RACHEL (READING SLIP OF PAPER): The defendant being found not guilty.

SOCIAL WORKER: Okay, it worries you a lot. We’ll talk about.

RACHEL: And then, what if one of them is HIV-positive? What about me?

SOCIAL WORKER: What we can do. We’ll ask her what the doctor said because they always do that. They check you, take your blood.

RACHEL: What if I do have it? I don’t want to look like them because they have also been raped.

PAKSIMA: Where have you seen them?

RACHEL: I see them on TV.

PAKSIMA: She’s afraid that what she sees on television will happen to her.

RACHEL: They’ll suffer and then they’ll die.

RACHEL (SINGING): I want to go to heaven in the morning

PAKSIMA: Children like Rachel cope however they can.

This little girl waited two hours to recite her poem.

LITTLE GIRL: AIDS

You are so cruel.

You are so sudden.

Nobody knows where you come from.

One of the good days a cure will come and you.

You will go back from where you came from and leave everybody in peace and love.

PAKSIMA: Despite the public outcry, little has changed.

KENYON: I can offer you something, okay?

PAKSIMA: And Barbara Kenyon will continue to help, even if it means sneaking anti-retrovrial medicine into this hospital to save two-year-old Thandiwe raped by her father.

Time is running out, and hopefully, you know, people in decision-making positions see the light.

RACHEL: I just want to say that children who are raped, they must speak the truth and then men will stop doing this to us.

It will get better.

PAKSIMA: Mary says when she grows up she wants to be a police officer.

MARY (TRANSLATED): She wants to catch people who are raping other kids.

RACHEL (SINGING): I want to go to I want to go to heaven to sing and shout I want to go to heaven in the morning…

PAKSIMA: Thank you, thank you so much.

MOYERS: The situation in South Africa became so desperate that this week, Nelson Mandela came out of retirement and attacked the government for its lack of response. He vowed to help mobilize South Africans to bring about change.

With us now is Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He has been a tireless voice for justice and racial reconciliation.

In 1984, archbishop tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in the struggle against apartheid.

Thank you, Archbishop Tutu for being with us.

ARCHBISHOP TUTU: Thank you.

MOYERS: Terrible things are happening all over the world to children, but we’ve just seen some horrible things happening to the children in your country.

Help me understand why there is so much child rape and abuse in South Africa.

TUTU: We have a terrible scourge in the HIV/AIDS pandemic, and people want to clutch at all sorts of things in the hope that they may be able to get a cure.

One of the most most ghastly myths that is going around is that if you are affected by the virus and you are HIV positive, to have sex with a virgin will cure you. Of course, the younger the victim, the more likely it is that she would be a virgin. And you have this awful, awful epidemic of grown-up men doing the kind of thing that you referred to.

MOYERS: Help me to understand this myth — I think of it as a superstition — that you just talked about. You’re a man of faith. How does something like that take hold in the imagination of a people?

TUTU: Well, it’s like any superstition. It is not based on anything that is rational.

MOYERS: Yet this one has such horrific consequences in the lives of these children.

TUTU: Absolutely, yes. We have to try and do everything we can to turn the situation around. It’s that there are craziness. And when you are inundated with problems — there is poverty, there is hunger, there is disease— you clutch on to anything that might seem to be going to relieve you.

It happens there but it happens in so very many other parts of the world.

MOYERS: How do you explain that the conviction…that the prosecution of so many of the men who are committing these rapes, there just hasn’t been much of it — what’s happened?

Why is the justice system broken down?

TUTU: Well, I don’t know that you can say it has broken down. It is under very considerable pressure.

Although one doesn’t keep wanting to use apartheid as a scapegoat, it is important to remember that, one, we had a police force that was not doing what an ordinary police force would be doing, such as being a crime-detection, crime-prevention agency.

It spent most of its time dealing with the opponents of apartheid, and there they didn’t use the normal judicial processes of the rule of law if they suspected you of being an activist, you were detained without trial. So they didn’t have to worry about being rigorous in doing things. So you are needing to transform an apartheid institution.

I have said that we are facing a kind of new apartheid and that we had a particular kind of commitment in the struggle against apartheid. And I’ve said, let’s invoke that same spirit in the face of this massive, massive challenge and let us stop the luxury of academic debates because people are dying.

MOYERS: Mbeki accepts the mainstream, scientific view on other diseases — tuberculosis, polio — but when it comes to what science, common sense and knowledge are telling us about aids and HIV, he just rejects it out of hand.

Why?

TUTU: Well, I don’t know that he’s rejecting it. In his view he’s not rejecting it out of hand. He does put forward some very clear views.

I myself would not go along with what he holds. But that is, in fact, not the important thing. The important thing is whether we can get the whole country mobilized and clearly seeing that this is a disease caused by this particular virus.

MOYERS: I don’t mean to be impolite, but it is a fact, Archbishop, that it is government policy right now not to distribute the retro viral medication to children who have been raped.

I cannot understand that.

TUTU: Yes.

They would contend that at the present time the indications are not clear about the effectiveness of the drug and the side effects. And I am not here holding a brief for them.

I am amongst those who would say that we really ought to stop playing marbles and do what is the conventional and the right thing to do.

MOYERS: What do you think the government should do right now?

TUTU: Yes. I myself would be a great deal happier if our campaign was single-minded and we said HIV, the virus causes the disease, let’s do everything to ensure that people where drugs that are effective are available are, in fact, given those drugs.

But that it must be a multifaceted approach. We’ve got to be engaging in vigorous education, teaching people about the importance of fidelity within the marriage union, that sex, extra marital sex, premarital sex, that that is something which is not to be accepted.

But that’s in an ideal world. We don’t live in an ideal world. Therefore we’ve also got to be teaching people about safer sex.

MOYERS: Is the world doing enough now to bring pressure on Mbeki and his government to help South Africa in this crisis?

TUTU: I believe that there are those who are concerned. I mean, pressure has never been enough at any time. I mean, there wasn’t enough pressure… We had to keep, hope, going on and say please help us. Go on, go on, go on.

I think what we should be doing is to be looking for those agents in South Africa that are going to be making a difference. We can’t just be waiting on government.

As I indicated to you, there are some extraordinary people in our country who are not sitting back and folding their arms, who are working like blazes to counteract, to do all they can to end this pandemic.

MOYERS: The little girl singing about wanting one day to go to heaven, if you were there right now, what would you say to her, that child, about faith in that hope and faith in men and the adults around her?

TUTU: I would say you see there are good people and point to those in her immediate vicinity who have cared for her, who have clothed her, who have given her toys and have said that not all are evil, not all are bad.

And it is important that we keep telling not just children but telling everybody, telling ourselves, that we have seen it happen in South Africa where evil seems to be on the rampage, where it seems to be going to carry the day. It hasn’t.

We expected an explosion that there would be a blood bath. It didn’t happen. People demonstrated in extraordinary magnanimity and generosity of spirit that where people had expected retribution and revenge, you saw forgiveness and reconciliation.

MOYERS: Thank you very much Archbishop Tutu and good luck to you.

TUTU: God bless you.

MOYERS: Africa, as a whole, continues to struggle with the AIDS epidemic. Some governments are tackling the problem head on.

We asked Dr. Roland Msiska, a public health specialist and Director of a United Nations Development Program on AIDS in Africa, to share some of those stories of hope with us.

DR. ROLAND MSISKA: Take the example of Uganda, for instance. A few years ago, everyone thought that the case of Uganda was a lost case where AIDS was concerned.

But now there is remarkable news that is out of Uganda. HIV Prevalence has been reduced from over 25% to now less than 8% in some urban areas.

There’s the case of Senegal, where, in fact, the HIV prevalence of anti-natal mothers in the city of Dakar has never gone beyond 2%.

Take the example of Zambia, where in the age group 15 to 19 years old, we have seen not only a reduction of 50% in that particular age group.

What has been the cause of the success in these countries?

One: an open political and religious leadership as far as the epidemic is concerned.

Two: the bubbling up of spontaneous community-based initiatives such as AIDS support organizations in Uganda, the Fuerita Initiative, organizations that have been looking after people living with HIV, and reducing stigma and discrimination in these communities, the engagement of various sectors in the community to respond to this epidemic, and of course, not forgetting the support that has come out from all these countries in the world for financial and material.

All these cases show that it is actually possible to respond to this epidemic in a way that is humane, in a way that is compassionate, in a way that can actually produce results, even in the such constrained environments.

MOYERS: Thank you, Dr. Msiska, for those insights.

Sexual abuse, of course, recognizes no political, national, or racial boundaries.

And here in America, as in South Africa, the attacker is not always a stranger.

The poet Linda McCarriston grew up in the Irish Catholic family in the town of Lynn, Massachusetts.

Her father sexually abused her for years, and it took a long time for Linda McCarriston to find the words to speak the unspeakable truth.

Here is an excerpt from our poetry series LANGUAGE OF LIFE

A Castle in Lynn

now hand is the hard bottom

of the girl. Now hand is full

of the full new breast. Now hand

—square hand, cruel as a spade—

splits the green girlwood of her body.

No one can take this from him now

ever, though she is for years a mother

and worn, and he is too old

to force any again. His cap hangs

on a peg by the door—plaid wool

of an elderly workingman’s park-bench

decline. I got there before

the boys did, he knows, hearing

back to her pleading, back to her

sobbing, to his own voice-over

like his body over hers: laughter,

mocking, the elemental voice

of the cock, unhearted, in its own

quarter. A man is king in his own

castle, he can still say, having got

what he wanted: in a lifetime

of used ones, second-hand, one girl

he could spill like a shot of whiskey,

the whore only he could call daughter.

MCCARRISTON: Poetry is about saying what we don’t want to know. Poetry is about saying the unsayable.

And in the case of these poems in this book, the unsayable was, quite simply, what…the brutal, horrible and cruel reality of the violence that has been a part of so many homes.

That particular poem of them all is the most painful for me because I think it gets most profoundly to the root of my experience as a girl-child in that family. The whore only he could call daughter. But this is not an exaggeration.

And there are many, many, many others with experiences in violent families. My task as a poet was to bring that brutal experience to light through poems. They’re rough poems. They’re painful poems. It hurts me to read them. It hurts people to hear them.

But, you know, poetry is about real life; poetry is about what kills us and what doesn’t kill us; it’s about what keeps us alive.

Poetry itself in my own life has been a tremendous avenue. It has been really the only avenue to speak the truth with power.

MOYERS: How do you decide to write about such unsayable experiences?

MCCARRISTON: I really don’t feel as though I had a choice. That was my material. And the difficulty was in simply waiting and leaning on that material long enough until a way came to me in which I could.

MOYERS: And poetry, what is it about poetry that enabled you to do this that prose didn’t have?

MCCARRISTON: That’s a very difficult question.

Poetry allows one to speak with a voice of power that is not, in fact, granted to one in our culture. For example, as a woman in this culture, I did not have the stature from which to speak.

I was simply a common woman. I was not a judge, I was not a priest.

There are several poems in the collection that make reference to efforts to speak or to get help.

From the priest, from the doctor, from the lawyer, from… And you have those in possession of power and authority.

NARRATOR: Now a look at stories coming up on NPR Radio this weekend.

LIANE HANSEN: I’m Liane Hansen from NPR news.

Sunday on WEEKEND EDITION meet musician Chuck E. Weiss, the coolest guy in Los Angeles and the inspiration for Ricky Lee Jones’ classic song “Chuck E.’s in Love.”

Join the party as Muslims celebrate the feast holiday of Eid al-Adha in post-Taliban Afghanistan.

And exercise your brain with puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

Find your local radio station on our web site, NPR.org, and join us.

MOYERS: With the debate that surrounded the passage of the campaign reform bill in the House of Representatives last week, we’ve all been made aware of the power of “soft money.” But what about the problem plain old direct contributions pose? And, how does this “hard money” influence votes on Capitol hill?

REP. MICHAEL OXLEY, (R-OH) Feb. 4th: This committee oversees the financial and capital markets we take our work very seriously, and we’re committed to doing what is right.

BILL MOYERS: It has become almost a daily ritual. The chorus of voices from Capitol Hill expressing anger and dismay over the collapse of Enron.

REP. W.J. TAUZIN (R-LA), Feb 5th: We have substantial evidence of illegal activity by Enron and its management.

REP. JIM GREENWOOD (R-PA), Feb 5th: Clearly, there is much troubling information in this report for us to consider as we move forward.

MOYERS: Among the most vocal critics-the chairmen of the Congressional committees investigating the Enron disaster.

PAM GILBERT, FORMER EXEC. DIR. CONSUMER PRODUCTS SAFETY COMMISSION:Sometimes you do shake your head and wonder, “where were they?”

MOYERS: Pamela Gilbert is the former executive director of the Consumer Products Safety Commission. She is also a lawyer who has spent much of her career fighting for the rights of investors.

GILBERT: I know full well that they know partly how this could have happened, because it’s been some of their handiwork that has enabled this kind of shenanigans to go on.

MOYERS: Gilbert is talking about several opportunities Congress had in recent years to enact safeguards to mitigate a scandal like Enron. But each of those efforts went down in defeat—shot down by some of the same politicians who are now investigating the scandal.

GILBERT: They were told over and over again that this was going to hurt real people…they just turned their backs on those arguments and sided with members of industry who were financing their campaigns.

MOYERS: One thing that might have helped prevent Enron: the so-called “auditing independence rule.” Three years ago, the Securities and Exchange Commission proposed a rule that would have stopped accounting firms, such as Arthur Andersen, from doing both auditing work and consulting work for the same company. The SEC saw this as an enormous problem. Such relationships were fraught with conflict of interest, they said. Lynn Turner was the Chief Accountant at the SEC.

LYNN TURNER, FORMER CHIEF ACCOUNTANT at the SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION: We were seeing cases where auditors had actually identified the problems during the course of the audit and knew the numbers were wrong, and yet still gave a clean bill of health on those numbers. And in some cases, the consulting fees were quite high, so we’re concerned about whether or not the consulting fees had led to a less than objective audit, if you will.

GILBERT: Well, when that same accounting firm is relying on that company to hire it to consult on all sorts of matters…its in the interest of the accounting firm to be very kind to the company.

MOYERS: And that’s exactly the kind of behavior for which Arthur Andersen is being investigated—ignoring wrongdoing at Enron so it could keep on collecting big consulting fees. The accounting firm pocketed 27 million dollars a year in consulting fees from Enron…at the same time it was making 25 million a year to audit Enron’s books.

GILBERT: As we’re seeing in the Enron situation, it’s hard to say Enron without saying Andersen as well. Everything that Enron did along the way, Andersen was there reviewing and giving a clean bill of health to their audits.

MOYERS: Andersen’s accounting division , like all auditors, is supposed to be an independent outsider-ready and willing to blow the whistle. By law, accountants are the guardians that are supposed to make sure corporate America isn’t cooking the books.

BARBARA ROPER, DIRECTOR, INVESTOR PROTECTION, CONSUMER FEDERATION OF AMERICA: There’s no way that accountants who have too much at stake in a client to be willing to walk away can claim to be independent.

MOYERS: Barbara Roper is director of investor protection for the Consumer Federation of America. The SEC enlisted the federation to help make the case in Congress for separating auditing and consulting work.

ROPER: Before there was even word one on paper of what those proposed rules were going to look like, the accountants were already up on the Hill, trying to line up members of Congress to back them in their opposition to the SEC’s proposed rule.

TURNER: You had the profession itself hiring lobbyists and doing a phenomenal amount of lobbying and putting a lot of money in the campaign re-election funds that year.

MOYERS: Members of Congress embarked on an aggressive campaign against the proposed rule. There were meetings, hearings, and most notably, a wave of protest letters to the SEC. We were shown some of those letters from Congress. Among them: three letters from Representative Billy Tauzin; two from Representative Michael Oxley. Both men are now chairing key committees investigating what Anderson did wrong.

TAUZIN, Feb 6th: We’ve also found that Enron’s auditor, Andersen, knew or should have known, or should have discovered, the fraudulent nature of the Fastow transactions.

MOYERS: Congressmen James Greenwood also holds a key position in the Enron investigation. He, too, opposed cleaning up the accounting rules.

REP. JAMES GREENWOOD, Feb. 6th: Enron’s accounting tactics went well beyond the aggressive, violating or circumventing some the accounting profession’s most basic rules.

MOYERS: Members of the Senate weighed in too, especially Democrats Charles Schumer and Evan Bayh and Republican Robert Bennett. All three now sit on Senate committees investigating Andersen and Enron.

ROPER: The accountants went to Congress and they lined up people who were willing to intervene, and I think a reasonable person assumes that the amount of money that the accountants gave influenced those decisions.

MOYERS: How much did the accounting industry give? Here are some of the figures.

Billy Tauzin is the number one recipient in the House of donations from the Andersen accounting firm. And since 1995, he received over $l53,000 from the accounting industry as a whole.

- Michael Oxley has collected over $87,000 dollars from the industry.

- Charles Schumer, $386,000.

- Robert Bennett, over $87,000.

- Evan Bayh, over $90,000.

All of that was in what’s called “hard money,” in other words, direct campaign contributions. To get around the $1000 limit on individual contributions, companies often use “bundling,” collecting checks from many employees and sending them in together. And that would still be legal under the legislation passed last week by the House.

Also, all of them have taken money from the Enron Corporation itself. We asked to interview several of these members of Congress; none accepted.

ROPER: I think most people do smell a rat. I mean, people believe that companies give money for a reason.

TURNER: I think there was a correlation, and in some cases a direct correlation, between the money that some members of Congress were receiving and their efforts, either through telephone calls, or meetings, or writing letters opposing the rule making effort.

ROPER: You know, thousands of people are out of their jobs, retirement plans that have been cleaned out. I mean, that’s what the evidence of a blown audit looks like, and it’s this cynical argument on the Hill you face, that there has to be blood in the water. You have to show the victims before you can get an effective response. And so now, we’ve got the victims.

MOYERS: In the end, the supporters of the accounting industry won-the independence rule never passed. But the woes of many of those Enron victims may soon grow even worse. Roper cites another example of how Congress helped the accounting industry.

ROPER: It is in many ways the same cast of characters. Many of these same people are the same people who were doing the accountant’s bidding on the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act.

MOYERS: The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act was passed in 1995. It’s what’s known as a “tort reform” law. It is an effort to reduce lawsuits, in this case, lawsuits by investors seeking to recover money for securities fraud—investors like those who owned stock in Enron.

ROPER: In the simplest terms, what it does is make it more difficult to sue for securities fraud. And should you successfully sue for securities fraud…makes it less likely that you will recover your damages.

GILBERT: One of its major elements was that it would relieve or very much limit the liability of people who assist in fraud. So they may not be the mastermind behind the swindle, but they are the accountants or the lawyers or the brokers who enable the fraud to go on.

MOYERS: Limit the liability of accountants like Andersen-now being sued for its Enron audits. And who wrote this law? Some familiar names: Billy Tauzin and Michael Oxley, Republicans, and, in this particular case, Senator Christopher Dodd, a Democrat. The accounting industry has given Dodd over half a million dollars.

GILBERT: The legislation was going to protect criminals and swindlers and white collar defrauders, and unfortunately, because of the gobs and gobs of campaign cash in the system the voices of the people with the special interests in the debate won out over the voices of the people who were going to be directly affected, which were consumers and small investors.

MOYERS: Small investors like Tom and Karen Padgett.

TOM PADGETT: At the high point…it was worth about $615,000. Today, it’s probably worth less than $10,000.

MOYERS: The Padgetts are one of those families that had a 401k plan with Enron. They were a few months away from retirement when Enron went into its death spiral. They’re part of a lawsuit to recover their money, but don’t hold out hope they’ll see much of anything.

KAREN PADGETT: If Enron doesn’t have the money, then where we gonna get it from?

MOYERS: Like many other people in 40lks, the Padgets made the mistake of keeping too much money in one pot-in their case, Enron stock. They say they believed the optimistic predictions being made by Enron management. But even these 401k losses could have cut by yet another proposal that ended up dead-on-arrival in Congress.

SENATOR BARBARA BOXER (D-CA): It’s Economics 101. When bad things happen, if your risk is spread, you’ll be okay.

MOYERS: In 1996, well before the Enron crisis hit, Senator Barbara Boxer was concerned about the need for diversifying 401k money, so she proposed a cap on holding too much company stock.

BOXER: So I said, look, I got to do something about this and I wrote a bill that would have put a ten percent cap on any one company’s stock…I got slaughtered, to be honest. I got slaughtered.

MARK IWRY, FORMERLY OF THE U.S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT:Well, the political battle was not that much of a battle back then.

MOYERS: Mark Iwry was a Treasury Department official who advised and supported Boxer’s effort to limit the amount of company stock in 401k plans.

IWRY: Unfortunately, there were very few others who were lined up in favor of working hard to protect the workers as much as possible and the forces who were in favor of the status quo were far more powerful and prevalent at the time.

BOXER: You know, certain things are clear. It’s clear that you’re going to put your whole retirement at risk if you’re not diversified. It’s clear that if an auditor is also making money from the company as a consultant, they just may not be willing to tell the truth. These things are clear. So the same people who are fighting me now fought me then, they’re the same people responsible for this problem.

MOYERS: There’s now a new effort to cap company stock in a 401k. Boxer hopes Congress has gotten the message. Meanwhile, thousands of people have lost their jobs, billions of dollars in investments have disappeared, and the leaders of Congress are on television practically everyday, asking, “How could this have happened?”

TAUZIN, Feb 6th: In the end, it turns out that the Enron debacle is an old-fashioned example of theft by insiders, and a failure of those responsible for them to prevent that theft.

TURNER: I would turn around and say that some of those up on the Hill who led the opposition to us also need to turn around and ask themselves the question, “What role did they play in not getting this problem fixed earlier?” And I’m willing to give them the benefit of the doubt at this point in time but at the end of the day, if we don’t get substantial reforms, then I would say that unequivocally, this is the irony of ironies.

BILL MOYERS: With all due respect, those members of Congress must know we know what’s going on.

They’ve come to scold the corpse that was once their best friend, and to prove they mean it, they will drive a stake through its heart, to make sure the cad never comes back from the grave. Just in case, they will also move soft money out of sight, to put themselves beyond temptation.

Sure, and it’s a good thing they’ve done, reducing their co-dependence on soft money. But like the alcoholic who stashes a bottle in the closet and one behind the books — Well, if you’re addicted to campaign contributions, there’s more than one way to slake your thirst.

Let me show you what I mean. Let’s say all of you watching right now were in one auditorium…right there, on the screen…and everyone is standing up. Okay, now we’ll ask all of you over here — this third of the auditorium — please sit down. You represent one-third of eligible adult citizens who are not registered to vote. You don’t matter in politics; you’re invisible.

Now we’ll ask all of you over here — this third of the room — to please take your seats. You were registered to vote but didn’t bother (shame, shame).

Those of you still standing are the active voters who decide elections. And by the way, there are about two-and-a-half times as many people in this group of decisive voters who make more than $75,000 a year than there are people making $15,000 or less.

Now we’re going to get to someone really special. Someone who truly counts in politics. All of you voters sit down…except you, yes, you, right there in the front row. Please keep standing.

You represent the roughly one-tenth of one percent of all Americans who actually wrote a check for $1,000 or more and gave it to a candidate for federal office, a political party, or a political action committee. There are 340,000 of you in the country — and you gave more than one billion dollars in the last election. That’s billion with a “b” – just 340,000 people out of 280 million of us gave $1,000 or more. It’s like letting the population of St. Louis choose the President and Congress.

Now for the kicker: the campaign reform bill passed by the House last week and now before the Senate actually doubles the amount of money an individual can contribute to congressional and presidential campaigns. So the same tiny elite will still be writing most of the checks…the same number of people…giving twice as much money. You, down there in the front row…you can bet your boots that of all the people in this auditorium, your name is the one in the politicians’ rolodex. They’ll take your call every time…And they’ll be calling you…again and again…for the bottle stashed away.

Hard, or soft, you see, in politics money decides who games the system. It’s why people who give the money get more of what they want. That’s okay in private life. Rich people should be able to buy more homes than anyone else, more cars, more travel, more gizmos. But they shouldn’t be able to buy more democracy.

Remember that when you’re watching the Enron hearings. It wasn’t soft money those politicians took. It was the old-fashioned kind…hard, enticing, and plentiful. And it’s not going away…

Or so it seems to me. Tell us what you think.

For NOW, I’m Bill Moyers.

This transcript was entered on March 19, 2015.