Britain takes control of the Cape

The arrival of the British at the Cape changed the lives of the people that were already living there. Initially British control was aimed to protect the trade route to the East, however, the British soon realised the potential to develop the Cape for their own needs.

Indigenous population

With colonialism, which began in South Africa in 1652, came the Slavery and Forced Labour Model. This was the original model of colonialism brought by the Dutch in 1652, and subsequently exported from the Western Cape to the Afrikaner Republics of the Orange Free State and the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. Many South Africans are the descendents of slaves brought to the Cape Colony from 1653 until 1822.

The changes wrought on African societies by the imposition of European colonial rule occurred in quick succession. In fact, it was the speed with which change occurred that set the colonial era apart from earlier periods in South Africa. Of course, not all societies were equally transformed. Some resisted the forces of colonial intrusion, slavery and forced labour for extended periods. Others, however, such as the Khoikhoi communities of the south-western Cape, disintegrated within a matter of decades.

Initially, a colonial contact was a two-way process. However, Africans were far from helpless victims in the initial encounter. Colonial contact was not simply a matter of Europeans imposing themselves upon African societies. For their part, African rulers saw many benefits to be had from maintaining relations with Europeans, and for a considerable period of time they engaged with Europeans voluntarily and on their own terms.

Most importantly, trade with Europeans gave African rulers access to a crucial aspect of European technology, namely firearms. More than anything else, those who had ownership and control over firearms were able to gather around themselves larger and larger groups of people. In short, the ownership of firearms turned into a status symbol and a means to gain political power.

Sadly, the article of trade in which Europeans showed the greatest interest, and which Africans were prepared to sacrifice, were slaves. The Atlantic slave trade stands at the centre of a long history of European contact with Africa. This was the era of the African Diaspora, an all embracing term historians have used to describe the consequences of the slave trade. Estimates of the number of slaves transported from their African homes to European colonial possession in the Americas range from 9 to 15 million people. Although a great deal of violence accompanied the trade in slaves, the sheer scale of operations involved a high degree of organisation, on the part of both Europeans and Africans. In other words, the Atlantic slave trade could not have taken place without the cooperation, or complicity, of many Africans.

As the number of transported salves increased, African societies could not avoid transformation, and 400 years of slave trading took their toll. Of course, not all African societies were equally affected, but countries such as Angola and Senegal suffered heavily.

The most important consequences of the Atlantic slave trade were demographic, economic, and political. There can be no doubt that the Atlantic slave trade greatly retarded African demographic development, a fact that was to have lasting consequences for the history of the continent. At best, African populations remained stagnant. The export of the most economically active men and women led to the disintegration of entire societies. The trade in slaves also led to new political formations. In some cases, as people sought protection from the violence and warfare that went with the slave trade, large centralised states came into being.

To read more visit our grade 10 archive lesson on Slavery

Postcard picture of High Street in Grahamstown, circa 1900. Source: Frescura Collection.

Postcard picture of High Street in Grahamstown, circa 1900. Source: Frescura Collection.

1820 Settlers

After the Napoleonic wars, Britain experienced a serious unemployment problem. Therefore, encouraged by the British government to immigrate to the Cape colony, the first 1820 settlers arrived in Table Bay on board the Nautilus and the Chapman on 17 March 1820. From the Cape colony, the settlers were sent to Algoa Bay, known today as Port Elizabeth.

Lord Somerset, the British governor in South Africa, encouraged the immigrants to settle in the frontier area of what is now the Eastern Cape. This was in order to consolidate and defend the eastern frontier against the neighbouring Xhosa people, and to provide a boost to the English-speaking population.

This period saw one of the largest stages of British settlement in Africa, and approximately 4,000 Settlers arrived in the Cape, in around 60 different parties, between April and June 1820. The settlers were granted farms near the village of Bathurst, and supplied equipment and food against their deposits. A combination of factors caused many of the settlers to leave these farms for the surrounding towns.

Firstly, many of the settlers were artisans with no interest in rural life, and lacked agricultural experience. In addition, life on the border was harsh and they suffered problems such as drought, rust conditions that affected crops, and a lack of transport. Therefore many settlers left the eastern border in search of a better life in towns such as Port Elizabeth, Grahamstown and East London. The eastern border therefore never became as densely populated as Somerset had hoped.

The settlers who did remain as farmers made a significant contribution to agriculture, by planting maize, rye and barley. They also began wool farming which later became a very lucrative trade. Some of the settlers, who were traders by profession, also made a significant contribution to business and the economy. New towns such as Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth therefore grew rapidly.

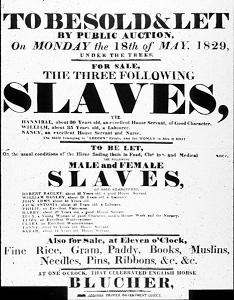

Slave ‘sale’ in Africa in 1829 is advertised on the same poster as the sale of rice, books, muslins etc. Source: chrislayson.com

Slave ‘sale’ in Africa in 1829 is advertised on the same poster as the sale of rice, books, muslins etc. Source: chrislayson.com

Changing Labour Patterns: the slave trade and it abolition

Slavery affected the economy of the Cape, as well as the lives of almost everyone living there. Its influence also lasted long after the abolition of slavery in 1838.

In South Africa under Dutch settlement, there was a shortage of labour, especially on the wheat and wine farms. But the VOC did not want to spend its money on the expensive wages that European labourers demanded. Nor could the VOC use the Khoi people as slaves. The Khoi traded with the Dutch, providing cattle for fresh meat. The Khoi also resisted any attempts to make them change their pastoralist way of life.

The Dutch were already involved in the Atlantic slave trade and had experience in buying and controlling slaves. They thus imported slaves as the cheapest labour option. Slaves were imported from a variety of places, including the east coast of Africa (Mozambique and Madagascar), but the majority came from East Africa and Asia, especially the Indonesian Islands, which were controlled by the Dutch at the time. This explains, for instance, why there are a relatively large number of people of Malaysian descent in the Cape (the so-called Cape Malays).

Initially, all slaves were owned by the VOC, but later farmers themselves could own slaves too. Slaves were used in every sector of the economy. Some of the functions of the slaves included working in the warehouses, workshops and stores of the VOC, as well as in the hospital, in administration, and on farms or as domestic servants in private homes. Some slaves were craftsmen, bringing skills from their home countries to the Cape, while others were fishermen, hawkers and even auxiliary police. The economy of the Cape depended heavily on slave labour.

The lives of the slaves were harsh, as they worked very long hours under poor conditions. They were often not given enough healthy food and lived in overcrowded and dirty conditions. Slaves had no freedom at all ”” they were locked up at night, and had to have a pass to leave their place of employment. As they were regarded as possessions, they were unable to marry, and if they had children, the children belonged to the slave’s owner and were also slaves. They also had little chance of education. Women slaves were at risk of being raped by their masters and other slaves.

A traveller, Otto Mentzel, observed that: “It is not an easy matter to keep the slaves under proper order and control. The condition of slavery has soured their tempers. Most slaves are a sulky, savage and disagreeable crowd ”¦ It would be dangerous to give them the slightest latitude; a tight hold must always be kept on the reins; the taskmaster’s lash is the main stimulus for getting any work out of them.” – Source: Mentzel, A Geographical and Topographical Description of the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Town, 1921

While there were many laws inhibiting the lives and movements of slaves, there were also rules to protect them, for example, female slaves could not be beaten. In theory, slave owners would be punished for treating their slaves badly ”” for example, if they went so far as to beat them to death ”” but the laws were often ignored.

The Abolition of Slavery Act ended slavery in the Cape officially in 1834. The more than 35 000 slaves that had been imported into South Africa from India, Ceylon, Malaysia and elsewhere were officially freed, although they were still bonded to their old masters for four years through a feudal system of “apprenticeship”. For many years wages rose only slightly above the former cost of slave subsistence.

The abolition of slavery and the emancipation of slaves caused a lot of resentment and opposition from the Cape colonials towards the anti-slavery lobby, as embodied in the

London Missionary Society that had put pressure on the British government to take this decision. Even before emancipation, the publicised cases of missionary intervention on behalf of mistreated black workers on farms, sometimes even winning convictions against farmers, made them enemies of the largely Afrikaner farming community in the Cape. Reverends John

Philip, Johannes van der Kemp and John Read were the most hated missionaries because of their fight for the rights of oppressed black Cape residents.

In fact, one of the reasons for the Great Trek, which would lead to the migration of many white, Dutch-speaking farmers away from the Cape after 1833, was the abolition of slavery by the British government. The farmers complained that they could not replace the labour of their slaves without losing a great deal of money. Importantly, the abolition of slavery did not change the colonial–feudal “slave–master” relations between black and white. Instead, these slave–master relations imprinted themselves on South Africa’s political, social and economic structures for years to come. Black people were “enslaved” by the oppressive laws of industrialisation, pass regulations, and labour ordinances such as the Masters and Servants Act of 1841, which made it a criminal offence for a worker to break a labour contract. It was only after 1994, and the dawning of democracy in South Africa, that all South Africans were truly emancipated from slavery.

For a useful and interesting article on slavery got to africanhistory.about.com

Expanding frontiers and trade

Boer responses

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Cape settlers were expanding their territory northeast. The Trek Boers seeking fresh grazing for their cattle, primarily, led this expansion. These cattle farmers had no fixed dwelling places and many led a semi-nomadic existence, moving ceaselessly between summer and winter pastures. As most trek farmers had large families, the system encouraged swift expansion. The Cape Government had done nothing to hinder expansion inland since it provided a source of cheap meat.

As the trekkers’ expansion increased, they inevitably came into conflict with, first, the Khoikhoi and later the Xhosa people into whose land they were encroaching. This marked the beginning of the subjugation of the Tembu, Pondo, Fingo and Xhosa in the Transkei. The Xhosa in particular fought nine wars spanning a century, which gradually deprived them of their independence and subjugated them to British colonial rule.

In the towns, tension was also increasing between settlers and the Dutch authorities, with the former becoming increasingly resentful at what they perceived as administrative interference. Soon the districts of Swellendam and Graaff-Reinette pronounced themselves independent Republics, though this was short-lived – in 1795 Britain annexed the Cape Colony.

This development and, in particular, the emancipation of slaves in 1834, had dramatic effects on the colony, precipitating the Great Trek, an emigration North and Northeast of about 12 000 discontented Afrikaner farmers, or Boers. These people were determined to live independently of colonial rule and what they saw as unacceptable racial egalitarianism.

The early decades of the century had seen another event of huge significance – the rise to power of the great Zulu King, Shaka. His wars of conquest and those of Mzilikazi – a general who broke away from Shaka on a northern path of conquest – caused a calamitous disruption of the interior known to Sotho-speakers as the difaqane (forced migration); while Zulu-speakers call it the mfecane (crushing).

Shaka set out on a massive programme of expansion, killing or enslaving those who resisted in the territories he conquered. Peoples in the path of Shaka’s armies moved out of his way, becoming in their turn aggressors against their neighbours. This wave of displacement spread throughout Southern Africa and beyond. It also accelerated the formation of several states, notably those of the Sotho (present-day Lesotho) and of the Swazi (now Swaziland).

This denuded much of the area into which the Trekkers now moved, enabling them to settle there in the belief that they were occupying vacant territory. Of these Voortrekkers, about five thousand settled in the area that later became known as the Orange Free State (present day Free State). The rest headed for Natal (present day KwaZulu-Natal) where they appointed a delegation, under the leadership of Piet Retief to negotiate with the Zulu King, Dingaan (Shaka’s successor), for land. Initially, Dingaan granted them a large area of land in the central and southern part of his territory but Retief and his party were later murdered at the kraal of Dingane.

The newly elected Voortrekker leader, Andries Pretorius, prepared the group for a retaliatory attack and the Zulu were subsequently defeated at the famous Battle of Blood River, 16 December 1838, leading to the founding of the first Boer Republic in Natal.

Xhosa response

Europeans who came to stay in South Africa first settled in and around Cape Town. As the years passed, they sought to expand their territory. This expansion was first at the expense of the Khoikhoi and San, but later Xhosa land was occupied as well. During the later half the 16th century, the Xhosa encountered eastward-moving White pioneers or Trek Boers in the region of the Fish River. The ensuing struggle was not so much a contest between Black and White races as a struggle for water, grazing and living space between two groups of farmers.

The first frontier war broke out in 1780 and marked the beginning of the Xhosa struggle to preserve their land, customs and way of life. It was a struggle that was to increase in intensity when the 1820 British settlers arrived on the scene.

This embittered struggle involved some of the greatest War Veterans in South Africa’s history e.g. renowned warrior Maqoma (the father of Guerilla Warfare), Sir Harry Smith (military legend and England’s favorite General), Chief Hintsa (martyr) and Adriaan van Jaarsveld (known as the ruthless ‘red captain’ among the Xhosa). It was also during these wars that the Trek-Boers developed the technique of the Laager as a way of defending themselves against a large enemy force.

Laager: A type of ‘military camp’, with 5-or more heavy wagons in a circle, and thorn trees thrust between the openings. In the middle were four wagons in a square, roofed over with planks and raw hides to serve as protection for women, children and the elderly. Here the farmers could defend themselves until reinforcements arrived or the enemy decided to retreat.

To read more about the VOC frontier wars and the British Frontier Wars visit SAHO’s detailed feature on the Frontier Wars.

– See more at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/britain-takes-control-cape#sthash.07LJVJTt.dpuf