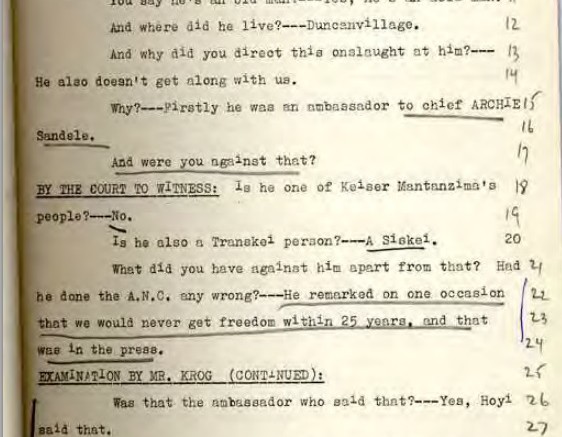

Often referred to as “the trial that changed South Africa,” in October 1963, ten leading opponents of apartheid went on trial for their lives on charges of sabotage. In what was arguably the most profound moment in the trial, Nelson Mandela made a speech in the dock in which he condemned the very court in which he was appearing as ‘illegitimate’. He then proceeded to argue that the laws in place were equally draconian and that defiance of these laws was justified.

The Rivonia Trial and the arrest of the MK high Command highlight a conundrum faced by those in the liberation struggle: the way that justice was often at odds with legality. Liberation movements, while rejecting the legitimacy of the racial minority state, were forced to deal with the legal system – when activists were apprehended they simply could not disregard it.

In the Rivonia Trial, the ‘accused’ addressed this problem by using the courts as a site of struggle. They argued that the law was drawn up without the consent of the majority; it was enforced to ensure the perpetuation of an unjust system, and therefore the struggle would be waged to establish a new system, including a legal system that would embody the values of a non-racial constitution that protected human rights.

The Trial 1963-1964

Rivonia Trialist supporters, led by Gertude Shope and other activists, outside the Palace of Justice. Source: Pretoria News Library

Rivonia Trialist supporters, led by Gertude Shope and other activists, outside the Palace of Justice. Source: Pretoria News Library

On 30 October 1963 ten defendants appeared in the Pretoria Supreme Court charged on two counts of sabotage. The specific charges the accused faced were: (1) recruiting persons for training in the preparation and use of explosives and in guerrilla warfare for the purpose of violent revolution and committing acts of sabotage; (2) conspiring to commit the aforementioned acts and to aid foreign military units when they invaded the Republic; (3) acting in these ways to further the objects of communism; and (4) soliciting and receiving money for these purposes from sympathisers in Algeria, Ethiopia, Liberia, Nigeria, Tunisia, and elsewhere.

The defence team comprised of Joel Joffe, who was the instructing attorney, Bram Fischer, Vernon Berrange, Arthur Chaskalson and George Bizos. The trial judge was Justice Quartus de Wet, with the Prosecution led by Dr Percy Yutar. The Verwoerd government was hoping for the maximum sentence for the accused i.e. the death penalty. From the outset, the defence team informed their clients that they should expect the worst. All ten accused pleaded not guilty to all charges.

For the accused, the courtroom became a new site of struggle. The defendants’ daily appearances in court drew large crowds that filled up the courtroom and streets outside the court. Many supporters were in violation of numerous influx control regulations, and the courts for them too, became new sites of struggle.

In presenting the prosecution’s case, Yutar claimed that the accused were all members of what he considered ‘a cabinet of the government soon after the overthrow of the state’. In this cabinet, Mandela was Deputy Minister and Minister of Defence, while Govan Mbeki was Minister of European Affairs. The rest of the accused each had a cabinet portfolio.

The state’s star witness had to have been Bruno Mtolo, who testified in camera as ‘Mr X’. Mtolo had been a member of the regional command of the Natal MK and had a photographic memory. He implicated Mandela and his co-accused by recalling various meetings and events where he was exposed to these leaders’ words and plans to overthrow the state. His reason for becoming a witness for the state was, he said, due to his disgust at how Sisulu and other top leaders were living a lavish lifestyle while he claimed to have been denied his ten-pound a week wage for his activities in the MK.

The most profound moment in the trial was probably Mandela’s speech in the dock. He condemned the very court he was appearing in as illegitimate. He then proceeded to argue that the laws in place were equally draconian and that defiance of these laws was justified.

The trial ended on 12 June 1964, with the court sentencing eight of the convicted to life imprisonment. Mandela, Sisulu, Mbeki, Motsoaledi, Mlangeni, and Goldberg were found guilty on all four counts. The defense had hoped that Mahlaba, Kathrada, and Bernstein might escape conviction due to lack of evidence that they were actually party to the conspiracy. However, Mhlaba was found guilty on all four counts and Kathrada was found guilty on one charge of conspiracy. Bernstein was found not guilty; but he was later rearrested, released on bail, and placed under house arrest. Soon afterwards he fled the country. Kantor was the only accused discharged at the end of the prosecution’s case.

Eight of the accused were incarcerated on Robben Island Prison, with the exception of Goldberg, who was sent to Pretoria Central Prison where he served 22 years. At the time Pretoria Central was the only security wing for white political prisoners in South Africa.

Soon after the trial defence lawyer Bram Fischer was arrested and put on trial for ‘supporting communism’. Many believe the state went after Fischer because the Rivonia trialists had not received the death penalty. Fischer’s case received much attention, as Fischer was an Afrikaner fighting against an Afrikaner government. He was sentenced to life in prison and was only released when he was critically ill.

‘The accused waved to the audience as they descended below the dock. Outside, as on the preceding day, large numbers of police, some with dogs, stood ready to control the crowds and avoid any embarrassing incidents or disorder. Among some 2,000 people present there were only a few hundred Africans who showed their emotions. They responded to news of the verdict with shouts of Amandla Ngawethu! and the clenched fist and upright thumb of the ANC. Some unfurled banners – “We Are Proud of Our Leaders” – which the police seized. All except Goldberg, the one white, were flown to Robben Island, the maximum security prison some seven miles from the shores of Cape Town.’

Extract from the book, From Protest to Challenge, A Documentary History of South African Politics.

The Launch of MK and the Liliesleaf Raid

Nelson Mandela, second from left, with members of the National Liberation Front of Algeria. In March of 1962 Mr Mandela received training from the Algerian National Liberation Front at bases of the latter across the border in Morocco. Source: Pretoria News Library.

Nelson Mandela, second from left, with members of the National Liberation Front of Algeria. In March of 1962 Mr Mandela received training from the Algerian National Liberation Front at bases of the latter across the border in Morocco. Source: Pretoria News Library.

The 1960s period marked an important watershed in South Africa’s struggle against Apartheid. The aftermath of the Sharpeville Massacre and the declaration of the subsequent State of Emergency in March 1960 signalled the beginning of a brutal and intensive phase of state repression.

The intensification of repressive laws and the erosion of political rights by the Apartheid regime made the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) the first causalities in an era of banishment. Forced underground, the ANC, PAC and other liberation organisations had to consider new tactics. In 1958 and 1959 key ANC and South African Communist Party (SACP) leaders were talking seriously about a move to armed struggle, concluding that peaceful methods had proved fruitless. The ANC created an underground military wing, called Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) or the ‘Spear of the Nation’, which was launched on 16 December 1961.

As its manifesto declares, MK was formed ‘to be a fighting arm of the people against the government and its policies of race oppression’. As part of the programme of action envisaged in the manifesto, MK units undertook just over 200 operations. Using mainly home-made incendiary devices, their bomb attacks intended to damage public facilities.

In 1962 Nelson Mandela undertook trips to Algeria, Nigeria, Tunisia and Ethiopia in an attempt to drum up support for MK and to arrange military training for potential recruits. Thereafter the organisation dispatched more than 300 recruits abroad for military training. The underground movement and armed struggle was taking shape. In response the government doubled efforts to arrest the leadership and undermine the liberation struggle. Police efforts included the use of informants to infiltrate MK.

…Here, from underground, is Walter Sisulu to speak to you…

Sons and Daughters of Africa! I speak to you from somewhere in South Arica. I have not left the country. I do not plan to leave. Many of our leaders of the African National Congress have gone underground. This is to keep the organisation in action; to preserve the leadership; to keep the freedom fight going. The struggle must never waver. We of the ANC will lead with new methods of struggle. The African people know that their unity is vital. In the face of violence, many strugglers for freedom have had to meet violence with violence. How can it be otherwise in South Africa?

– Extract of the inaugural broadcast made by Radio Liberation, the ANC’s radio station, on 26 June 1963. Sisulu and other leaders were arrested during a raid at Liliesleaf farm less than a month later.

Aerial shot of Liliesleaf Farm showing the main house and out-houses. Source: South African National Archives

Aerial shot of Liliesleaf Farm showing the main house and out-houses. Source: South African National Archives

In the early 1960s the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the MK High Command purchased an isolated farm, called Liliesleaf, in Rivonia. It was agreed that Arthur Goldreich and his family would live in the main farmhouse, while the outhouses would be used as a meeting place for many of the luminaries of the struggle. It also proved perfect as a hide-out for banned activists from the ever-present and highly efficient police and security services.

Acting on information from an informant, the Special Forces raided Liliesleaf farmhouse on 11 July 1963.

When the police came through the door, they found a group of men studying ‘Operation Mayibuye’ – an MK proposal for guerrilla warfare, insurrection and revolution. Among the group were Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mahlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Arthur Goldreich, Dennis Goldberg and Lionel Bernstein.

Hundreds of incriminating documents were found during the raid, and members of the group were immediately arrested. Bob Hepple, part of the group found and arrested on the property, tried to burn documents related to Operation Mayibuye during the raid, but failed.

The group was arrested with the police relying on the 90-day detention law to delay their appearance in court while investigations continued. During this time more arrests followed, including that of Harold Wolpe, a lawyer who had used SACP funds to buy the farm; James Kantor, who was not involved in MK or in politics but was a legal colleague and brother-in-law of Wolpe; and MK Cadres Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni, who were linked to the farm through their fingerprints.

During this 90 day period – Nelson Mandela was added to the list of accused as evidence linking him to the farm was also found. Mandela was already serving a five-year sentence for his role in the campaigns of 1961 intended to disrupt Republic Day celebrations.

During their detention, Goldreich and Wolpe bribed a prison guard and made a spectacular escape, and Hepple was released on bail after three months in solitary confinement. He was told that he would be called as the first witness for the State. Rather than testify he fled the country.

Reactions, the impact of the Trial

International reactions

ANC President Oliver Tambo addresses a crowd outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square, London. This address occurred soon after the Rivonia Trial to maintain international pressure on Apartheid South Africa. Photograph from Sunday Times, supplied by STE Publishers

ANC President Oliver Tambo addresses a crowd outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square, London. This address occurred soon after the Rivonia Trial to maintain international pressure on Apartheid South Africa. Photograph from Sunday Times, supplied by STE Publishers

The media presence and coverage of the Rivonia Trial was significant. The Trial was watched by the world. As a result South Africa experienced pressure from the International Community during and after the trial. The United Nations issued statements to the South African government appealing against the death sentence, which many expected.

In addition, those listed as the co-conspirators during the Rivonia trial – namely Oliver Reginald Tambo, Joe Slovo, Ben Turok, Duma Nokwe, Joe Modise, Gertrude Shope, Jack Hodgson and others – were in hiding or in exile. Many of them helped to raise funds for the accused and organised many anti-Apartheid protests abroad.

In the aftermath of the trial the International Olympic Committee, FIFA, and other international sports bodies began terminating South Africa’s membership to these organisations. By the end of the 1970s, South Africa was largely isolated from participating in world sport. Cultural bodies around the world also terminated South Africa’s membership.

Effect on the struggle

The Rivonia Trial had significant short and long-term consequences. Many observers note that b y imprisoning the leaders of MK, the government was largely able to break the strength of the struggle inside South Africa, and for a time open political activity was nearly impossible . Others note that the liberation movements strengthened their underground networks and continued to create organisational capacity outside of the country.

When the ANC was banned in 1960, Oliver Reginald Tambo became the Acting President of the ANC after the death of Chief Albert Luthuli. He also assumed leadership of the movement abroad. The ANC set up bases in Dar es Salaam for the training of MK recruits. However, during the first half of the 1960s, it was difficult for MK to establish external bases from which to conduct operations. This problem diminished with the coming of independence: Zambia (1964), Botswana (1966), Lesotho (1966), Swaziland (1968), Mozambique and Angola (1975). In 1965 the ANC relocated its headquarters to Morogoro, but its main military camp was at Kongwa.

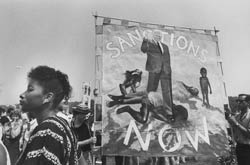

Anti-Apartheid Rally for Sanctions against the South African Government, London, 1986. Photograph by Paul Weinburg, supplied by South African Media Online

Anti-Apartheid Rally for Sanctions against the South African Government, London, 1986. Photograph by Paul Weinburg, supplied by South African Media Online

The watershed Morogoro Conference (1969) ushered in a new era in the history of the liberation struggle. It opened up ANC membership to all races. It also embarked on establishing more military bases in African countries. This period was characterised by an increase in efforts to enter South Africa through neighbouring countries in order to launch guerrilla attacks.

The late 1960s also saw a resurgence of resistance emanating from structures inside the country. This started in 1968 with the establishment of the South African Students Organisation (SASO) and the Black People’s Convention (BPC) in 1972. The re-organisation of political structures, particularly the youth, led to the Durban strikes of 1973 and later the student uprising of 1976. The 1976 Uprisings led to the intensification of armed struggle as thousands of youth fled into exile, swelling the ranks of MK.

Trialists’ release and transition to democracy

In the 1980s various liberation organisations began creating internal structures, like the UDF, to render the country ungovernable. Both the internal and external pressures forced the regime to open dialogue with the incarcerated leaders of the struggle.

Early in 1985 the government permitted Lord Bethell, a British Conservative Member of Parliament (MP), to interview Mandela in Pollsmoor. Pollsmoor was the mainland prison in Cape Town to which Mandela and five others had been transferred in 1982. Lord Bethell joined many in urging the South African government to release Mandela in the interests of achieving a negotiated solution. On 31 January 1985, President PW Botha responded by offering to free Mandela if he renounced the use of violence – an offer that Mandela refused.

In the meantime the situation inside South Africa had become increasingly unstable. The government declared a State of Emergency in 1986, and brutally targeted opponents of the government. These government measures merely fuelled the struggle fires.

In 1989, amid momentous global changes marked by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Apartheid government appeared ready to negotiate.

In 1989 FW de Klerk became President and soon afterwards he announced the release of various political prisoners. Nelson Mandela was released on 11 February 1990.

The Law Today

Between 1990 and 1993 the government was involved in negotiations with numerous political formations. Initial interactions led to the formation of CODESA I and II, culminating in South Africa’s first democratic elections of 1994 and the birth of our new constitution.

The Suppression of Communism Act of 1950 and the Internal Security Act were some of the pieces of legislation used by the Apartheid government to undermine the political activity of mainly Black people. These acts ensured that eight of the accused in the Rivonia Trial were sentenced to life in prison. After this trial other pieces of legislation were passed that would further restrict political activity or deny it completely for black people and others opposed to Apartheid. Some of the key pieces of legislation include Section 6 of Terrorism Act, passed in 1976, and the Criminal Law Amendment Act, passed after the Rivonia Trial. Both were used extensively in later politically related trials.

Today, the protection of our civil liberties is guaranteed in the Constitution of 1996. This allows for opposition to the government without the risk of facing arrest and possible imprisonment for political offences. It is no longer a political offence to be a member of any political organisation. It is no longer illegal to publish record or make statements that could be considered ‘security risks’.

Towards Reconciliation

Towards the end of the 1990s, at the request of cabinet, Bishop Desmond Tutu led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Many struggle leaders did not feel compelled to appear in front of the TRC as their main focus was on building a non-racial, non-segregated country, where everyone’s human rights are respected and, most importantly, protected. The TRC process was the government’s attempt to start healing the wounds of Apartheid experienced by both the victims and casualties of war. Although forgiveness was the outcome for many who chose to appear in front of the TRC, forgetting is more difficult. Many Apartheid victims, on both sides, still wear their scars in memory wherever they go.

Corruption, crime and violence against women and children are some of the issues facing our democracy today. While we have a constitution that protects our rights, our country’s legal system and government still has a long road to walk towards justice for all.

‘We, that is the Rivonia group, arrived on Robben Island on the 13th of June 1964. It was a Saturday – cold, windy, raining. We cannot forget the first months at the quarry where we mined stone – we came back with blisters, bloody hands, and sore muscles. And we cannot forget the dozen years or more when we were forced to sleep on the cold cement floors with three blankets and a thin sisal mat. Also we cannot forget the cold showers for 13 or 14 year. There is so much more that one can recall much more that we have found in ourselves to forgive, but these we will never forget’.

Ahmed Kathrada on opening the “Esiqithini: The Robben Island Exhibition” 26 May 1993

• Bulpin, T.V. (1985). Reader’s Digest Illustrated Guide to Southern Africa. Cape Town: Reader’s Digest Association South Africa, pg 412.

• Thomas Karis and Gail M. Gerhart (1977). From Protest to Challenge. A Documentary History of South African Politics in South Africa, 1882-1964. Volume 3, Challenge and Violence, 1953-1964. Hoover Institution Press pp. 673-684.

• Joel Joffe (2007). The State vs. Nelson Mandela: The Trial That Changed South Africa. One World Books.

• Bob Hepple (2009). Rivonia: the story of accused no.11. Unpublished manuscript.

• Various original documents and archival resources from the South African National Archive.

• Nelson Mandela’s military training www.nelsonmandela.org Various original documents and archival resources from the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

• Interviews on the Rivonia Trial:

– George Bizos

– Andrew Mahlangeni

– Ahmed Kathrada

All of these interviews were conducted by Pambili Productions between 2009-2011.

– See more at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/rivonia-trial-1963-1964#sthash.loPHhuWA.dpuf