The year of 1985 signalled the beginning of the end of apartheid society and governance in South Africa. Following an upsurge of violent and non-violent resistance to the racially-exclusive system of apartheid – which had seen the minority White population of South Africa exclusively govern and control the social, economic and political mechanisms of everyday life for 37 years – the apartheid government, under PW Botha, declared a partial State of Emergency on 21 July 1985. This moment of draconian law enforcement against the majority Black, Coloured and Indian population of South Africa proved a focal moment in the struggle against apartheid, as the international condemnation of the apartheid regime and other internal factors contributed to the rejuvenation of the grass-roots resistance inside and outside the country. The apartheid government’s use of extreme force as a means of governance was justified in ways that ranged from the belief of an imminent external Communist (Die Rooi Gevaar) attack; to ‘maintaining peace and order’ which was threatened by the increasingly ‘ungovernable’ nature of the Black townships and radical Black nationalists throughout the country.

The partial State of Emergency initially applied to 36 magisterial districts in the Eastern Cape and the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vereeniging area. However, with continued resistance throughout the country, the Act was eventually enforced nationally in 1986. The apartheid government’s resorting to emergency measures was read by many as an act of desperation as the political and social climate of South Africa revealed that White-minority rule was not in a secure or popular long-term position. In attempting to regain absolute control, the apartheid regime enforced a partial State of Emergency in 1985 in order to mediate and micromanage the following: media coverage, curfew times and movement for citizens, individual and group organisational capacity. The apartheid government’s complete clamp-down of citizens’ rights resulted in the numerous house arrests of influential anti-apartheid leaders, and the detaining of 2346 people under the Internal Security Act, in the attempts of ending internal resistance to the state’s power. Under the State of Emergency, the apartheid government militarised and heavily policed all aspects of South African society – which heightened feelings of mutual tension, paranoia and distrust between white South Africans and Black, coloured and Indian South Africans. Though effective in disrupting a number of anti-apartheid organisations by arresting a number of their leaders, the State of Emergency was not effective in ‘governing the ungovernable’ townships, as violent protest and fierce resistance continued against the state.

In commemorating the 30th anniversary of the State of Emergency that made apparent the weaknesses in the apartheid state’s system – which eventually contributed to the downfall of the aforementioned government.. It is apparent that the State of Emergency of 1985 played an important role as a catalyst of continued and more aggressive resistance against the apartheid state.

State of Emergencies: The Apartheid Government’s Bread and Butter

The apartheid government became notorious for its use of State of Emergencies in an attempt to exert complete control over Black, coloured and Indian South Africans. Control was not limited to controlling the freedom of movement of the aforementioned groups, but also included: the right to physical integrity; freedom of expression and of information; freedom of association; freedom of political association; freedom to gather and demonstrate peacefully; and the rights to personal freedom, among others. By attempting to control and dictate every minute aspect of Black, coloured and Indian South Africans’ lives, the apartheid government wanted to ensure that White-minority rule in the country was not only (willingly or unwillingly) accepted by these excluded groups, but was seen as a natural and long-term institution in order to maintain White South Africa’s economic prosperity. Under PW Botha, the apartheid regime would go on to use State of Emergencies as a normalised governing tactic as it allowed the state to ‘legitimately’ use not only the South African Police (SAP), but also the South African Defence Force (SADF), to violently repress any resistance against the state.

In the enforcement of a State of Emergency, the South African Law Commission states that the aforementioned rights and freedoms of citizens can only be legally interfered with by the state only if there is a threat to “considerations of state security, public order, public interest, the boni mores, public health, the administration of justice, conflict with the rights of others and the prevention of chaos and crime. Such curtailment is, however, permissible only to that extent and in such a manner as is generally accepted in a democratic society.” (Article 30) The South African Law Commission further states that a State of Emergency can only be enforced if the following occur beyond reasonable doubt:

1. The extraordinary machinery inherent in state security may only be utilised if and when the continued existence of the state as such is in question.

2. Security legislation itself must be limited: “Order and rule are needed to maintain freedom, but vigorous restraints are needed to contain rulers within the bounds of a constitutional order which protects human rights.

In reality, the enforcement of these emergency measures in South Africa did not strictly adhere to these considerations, as the apartheid state was established on politically, socially, economically, and racially-exclusive legislation; which saw the majority of the country’s population excluded from these spheres of South African society.

Under the emergency measures employed by the apartheid regime, media freedom was severely curtailed. This included the prohibition of media from publishing any information pertaining to detainees; the filming, recording, publishing and broadcasting of material concerning public disturbances and the dissemination of photographs, drawings and sound recordings. This heavy censorship applied both to print and television media, with the apartheid state consciously dictating what could or could not be published and broadcast, with dissenters and critics of the apartheid government also heavily censored. An example of a newspaper that was directly affected by the government-endorsed censorship was The Rand Daily Mail of Johannesburg, which was forced to shut down in 1985- the year of the partial State of Emergency.

Internal Anti-apartheid Resistance

Following the increased efforts by the apartheid government to retain control of South Africa’s political, economic and social spheres, resistance against the state came in different forms. Within the country, resistance came from various civic groups, trade unions, church organisations and political organisations. The African National Congress’ (ANC) internal influence was limited by the banning of the party, and the subsequent exiling of many of its leaders across the world. One of the most prominent organisations was the United Democratic Front (UDF), which was established on 23 January 1983 and comprised of over 400 organisations, with non-racialism being the main ethos. At its peak, the UDF had over 3 million active members throughout the country. In April 1985, the UDF – under the de facto leadership of Reverend Alan Boesak – established closer and more effective links with trade unions, church groups and other civic organisations against the continued social, political and economic exclusion practiced by the apartheid government. One of the biggest moments of resistance practiced by the UDF was the opposition to the establishment of the Tricameral Parliament in 1984. Under then Prime Minister PW Botha, the Tricameral Parliament was a shallow attempt at reforming the racially-exclusive structures of apartheid by including coloured and Indian representatives into Parliament. The lack of Black representatives in this ‘reformed’ structure was met with great resistance, along with the limited and superficial representational powers given to coloured and Indian representatives.The apartheid regime, with Botha at the helm, promised real reform for marginalised Black South Africans. The reform however is limited to Blacks in urban areas; with the promise of ‘future’ reform for Blacks confined to the ‘homelands’. This reform is largely criticised by anti-apartheid resistance movements, for being disingenuous and not wholly inclusive. On 25 May, the government enforced the Prohibition of Political Interference Act, which repealed the banning of racially-mixed political organisations. This move effectively diluted the organisational capacity of anti-apartheid groups as many of them advocated for non-racialism.

The enforcing of the partial State of Emergency, along with the Tricameral Parliament severely curtailed the already-limited individual and collective human rights of Black, Coloured and Indian South Africans. In response to this, resistance from the UDF increased with Boesak calling for a march to Pollsmoor Prison in protest. Following his role in resisting the state-sanctioned changes, Boesak was detained by the Police in order to limit his influential charisma and fervour against the apartheid state. The National Party responded to the continued insurrection by taking a harder stance against resistance from the ANC, UDF, civic groups and individuals fighting against the state. The ANC-in-exile, led by Oliver Tambo reaffirmed its commitment to “making the country ungovernable”, much to the detriment of white South African economic and political interests. Sabotage became an effective weapon of resistance against the apartheid government. Examples include the attacking of power plants, the bombing of shopping centres and businesses and the bombing of South African national essential services.

Three months after the enforcement of the partial State of Emergency, PW Botha continued to suggest that Black South Africans could potentially have their South African citizenships restored- following it being stripped when all Black South Africans were designated ‘ethnic homelands’. However, these promised reforms by the apartheid state never fully materialised. On 25 October, the Partial State of Emergency was extended to include Cape Town – following a spike in violent protest in the designated Coloured areas- and seven surrounding areas. In continued efforts to stem the flow of negative coverage on the government’s failure to quell resistance in Black and Coloured townships, newspaper, radio and television coverage of ‘unrest’ in these townships was banned by the state. This ban was enforced under the Newspaper and Imprint Act 63 of 1971. In a blow to anti-apartheid resistance, The Rand Daily Mail, a leading anti-apartheid publication, is controversially shut down. This loss of a critical voice against the state arguably provided the government with more momentum in enforcing censorship. A number of anti-apartheid leaders disappeared or are murdered under mysterious circumstances, with most deaths arguably occurring in detention. Due to the enforced Partial State of Emergency, the police had sweeping and absolute power to detain persons without a warrant and without the prospect of appeal or representation. These powers were enforced under the Internal Security Act 74 of 1982. This meant that the apartheid state constitutionally legitimated the use of excessive force in order to apprehend ‘questionable’ and ‘security-threatening’ targets.

The apartheid state continued to respond violently to any perceived form of “protest” or “gathering” that might threaten state security. Particular events that mark the government’s particularly aggressive responses include the 25 th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre, where 17 people were killed during a commemoration in Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape. The government further sought to restrict any opportunity for resistance by arresting leaders within the UDF on 18 February 1985. Six of the thirteen arrested were charged with High Treason.

External Pressures to the Apartheid State

Political pressures from anti-Communist United States of America and Britain – under the conservative leadership of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher respectively – were exerted on the apartheid state, with the intention of keeping South Africa a capitalist state. America and Britain chose to controversially follow a ‘constructive engagement’ stance with apartheid South Africa where it sought to ensure free trade with the state.

This is particularly important as the waning Cold War had effectively separated the world into different spheres of influence for the United States and for the Soviet Union; with many African countries becoming involved in proxy wars that were indirectly influenced by the USSR and the USA. The apartheid administration feared a communist attack and went to great lengths to ensure that Die Rooi Gevaar (‘Red Danger’) would not threaten white South Africa’s diplomatic, political and economic relations with America and Britain. The ANC’s socialist leanings and the presence of its cadres in Russia also acted as a deterrent to the apartheid state, as they feared a creeping coup that would see the white-minority rule overthrown. Margaret Thatcher famously declared the ANC a “terrorist organisation” and with Reagan attempted to ensure that apartheid South Africa remained a ‘bastion against Marxist forces’.

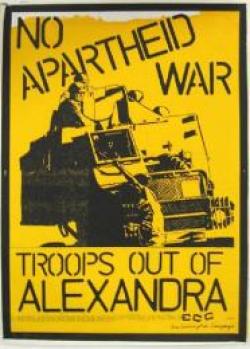

The apartheid state also attempted to extend its influence into Southern Africa, with the intention of supporting the governments of any state whose main intentions are to perpetuate white-minority rule. The government militarily interfered in the following countries, with varying degrees of success: Rhodesia (now independent Zimbabwe), Mozambique, Angola, Botswana and Namibia amongst others. This strategy was termed Total Onslaught. Apartheid South Africa’s ill-advised continental interventions was hugely unpopular within the country, with one of the most noted oppositions coming from the End Conscription Campaign, where a number of white South African men – who were the only group for whom military conscription was compulsory – protested their involuntary conscription into the SAF. South Africa’s involvement in Southern Africa has often been compared to the United States of America’s disastrous campaign in Vietnam. The SAF continued to attempt to apprehend ANC and any other organisation members outside of the country. This culminated with the attacking of various ANC bases across Southern Africa, with 15 people being killed in Gaborone, Botswana. Pik Botha, as Minister of Foreign Affairs, cuts an aggressive figure as he condemns Botswana – and by extension, other Southern African countries – for housing anti-apartheid activists and having ANC bases. Following this, the ANC continues to encourage South Africans inside the country to take the ‘ungovernable’ acts of resistance into white areas. This was done in the hopes of making white South Africans- consciously or unconsciously unaware of the escalating violence and continued military repression in the townships- aware of the brutal nature of their government and its continued flouting of international human rights.

The partial State of Emergency of 1985 proved to be an important moment in the resistance against apartheid. PW Botha’s regime faced international condemnation for its continued human rights abuses on Black, Coloured and Indian South Africans. Furthermore, the once-secure support of America and Britain was disrupted by the Cold War reaching its close, and the enforcement of economic sanctions – which would go on to cripple the country’s economy. Inside South Africa, resistance against the state continued to be met with violence and repression, which further isolated the government from its own disillusioned white citizens. The organisational power of the UDF and the ANC-in-exile also contributed to making the country ‘ungovernable’, with acts of sabotage and marches against the state becoming common. The partial State of Emergency exposed a number of weaknesses within the apartheid administration, which were strategically targeted by anti-apartheid resistance groups. These weaknesses essentially highlighted that the project of apartheid was not realistically feasible as a long-term system due to its racist and racially-exclusive ethos. The partial State of Emergency acted in essence as a unifier and mobiliser of unstoppable anti-apartheid resistance- which would later see FW De Klerk and his regime enter into negotiations with the ANC and various stakeholders, with regards to transitioning towards a non-racial and democratic South Africa.

• Gastrow, S., (1995). Who’s Who in South African Politics, no. 5. Johannesburg, Ravan Press.

• South African History Archive (2015). Commemorating the End Conscription Campaign. Available at http://www.saha.org.za/ecc25/ecc_under_a_state_of_emergency.htm

• Overcoming Apartheid (2015). State of Emergency in the mid-1980’s. Available at http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/multimedia.php?id=65-259-16

– See more at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/state-emergency-1985#sthash.yc29gnu0.dpuf