RAY Hartley tweeted this week, in response to a story about the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) canning a show on the now infamous Gupta family: “As the old saying goes, if you want to capture the state, start with the state broadcaster.” He is a sage observer is Hartley, but the fact is the SABC was captured ages ago. Open that door and the ANC’s systematic approach to state capture makes the Gupta family’s influence look like mild beer.

“State capture” and “The Guptas” are two ideas that have recently captured the public’s imagination. The South African public often exhibits these sorts of fashionable spasms. An idea, ostensibly novel, somehow makes its way into the national dialogue and, overnight, its grip on how we think and analyse current affairs becomes almost hegemonic in its reach and depth. As long as the spasm holds there is no other universe. Everything is seen and interpreted through that lens.

But the truth is the African National Congress (ANC) has been in the business of “state capture” for an awful long time, and it has laid out its plans to this end time and time again. Often they have not only been defended by the selfsame public mind, but endorsed by voters as perfectly acceptable behaviour in election after election.

In principle, “state capture” is not a problem for the majority of South Africans, they fairly love the idea. No, its state capture by the Gupta family — an unelected third force — that they take real issue with.

“Let’s get back to the good old days,” people seem to be complaining, “when the ANC was the only one doing the capturing.”

In the ANC’s political lexicon, “state capture” was set out at the party’s 1997 Mafikeng conference in the adoption of a cadre deployment resolution, whereby those loyal to the party would be placed throughout the state in order to deliver to the ANC control over the “key levers of power”. Sound familiar?

By “key levers of power” it didn’t mean those institutions a majority party can be rightly expected to control, but the public service and those independent bodies that comprise the state. It wanted them all to bend before its will. Public servants, of course, are responsible to the constitution and have to act in the interests of all, not just the governing party of the day.

And yes, those institutions included the SABC, although, somewhat ironically, it was among the last to fall.

Here are the particulars:

At its 1997 Mafikeng conference, the ANC constitution was amended to place all ANC structures — including ANC caucuses in the legislatures — under the supervision and direction of the party’s leadership. The national working committee was given responsibility for ensuring all ANC structures carried out the decisions of the national executive committee (NEC).

The conference also adopted a cadre resolution which mandated the national working committee to deploy cadres to the key centres of power it identified, establish committees at national, provincial and local level to oversee deployment, and draw up a comprehensive cadre policy and deployment strategy.

The commission on governance at Mafikeng stated that to increase the “hegemony” of the ANC, the party needed to have a “conscious strategy” to deploy cadres to institutions in civil society, such as the media and business.

The ANC’s Umrabulo June/August 1998 edition contains the document, The State, Property Relations and Social Transformation: A Discussion Paper towards the Alliance Summit. It states, among other things: “Transformation of the state entails, first and foremost, extending the power of the National Liberation Movement over all levers of power: the army, the police, the bureaucracy, intelligence structures, the judiciary, parastatals, and agencies such as regulatory bodies, the public broadcaster, the central bank and so on.”

It was a remarkably successful business for well on ten years, until, inevitably, the conscious decision to reward party loyalty ahead of merit and public service began to manifest overtly in corruption, mismanagement and decay. At the height of his powers, President Thabo Mbeki had pretty much every inch of the country sewn up.

And the SABC makes a good illustration of the point. In 2007, Dr Snuki Zikalala served as the SABC’s director of news. At board level, CEO Dali Mpofu had served the ANC as deputy head of its Social Welfare Department; board chairman Eddie Funde has a list of ANC credentials that ran from managing the placement, education and training of the hundreds of young ANC exiles during the 1970s to serving on the ANC’s NEC in 2002. Another board member, Solly Mokoetle, ran Radio Freedom for the ANC in exile, while Christine Qunta would often take to publicly flaunting her loyalty to Mbeki, not least by taking out full-page newspaper adverts on his birthday.

But the ANC’s conflation of party and state does not stop there. When SABC board member Cecil Msomi was not serving the public broadcaster he was working as the director of communication for the KwaZulu-Natal premier. In other words, he was employed by the ANC government to promote the political message and programme of action of its premier in that province.

Through all of them the SABC was turned into a supine and political tool in the ANC’s hands. This is cadre deployment at its zenith. The SABC is one illustration of it but, actually, you could apply the exact same test to almost any institution and the same ingredients for power and patronage would reveal themselves.

Jacob Zuma, as is his wont, has made a mighty mess of it all. Any pretense the system was designed to serve the party’s centralised agenda was soon usurped by his own, more powerful personal interests and, exacerbated by the Polokwane fracture that has run through the party ever since his election, the whole thing turned into a factionalised bun fight. Institutions imploded and the rot, ignored, justified away and downplayed for years, ate into the supporting infrastructure of so much.

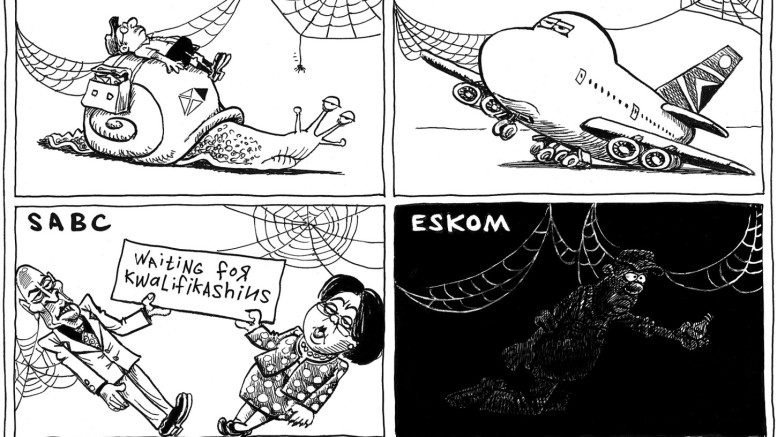

The result is today we are left with hollow institutions; if not broken then creaking and straining under their own fragility.

Amid the mess, all indications are the Gupta family has made itself right at home. Surprise, surprise. All they have done is unofficially privatise the idea. The shock and awe people demonstrate when pondering how it is they could possibly have infiltrated the state to this degree is itself somewhat puzzling. What exactly did they expect? Those constitutional bulwarks set up to protect the state’s independence have long since been whittled away. It’s a free-for-all out there, the Gupta family has obviously just been particularly shrewd about how to go about securing its own interests.

And they were whittled away not by neglect or indifference but rather by a very conscious and deliberate strategy on the part of the ANC to capture the state.

“State capture” is a wonderful rhetorical device. But it’s empty on its own. The mechanics of state capture — now there’s a thing. And in the ANC cadre deployment resolution you can find it all set out in fine detail.

Perhaps the Gupta family is to be thanked for one solitary thing: they have forced South Africans to identify the subversion of a principle that has been staring them in the face for nearly two decades. Many have taken much delight out of how certain members of the ANC have united behind this outrage, even at the expense of their president.

Gwede Mantashe, for one, seemed to waste no time taking a firm stance against any potential threat the Gupta family might present to ANC control. The hypocrisy. He is not interested in independence, transparency and best democratic practice. He just wants control returned to the ANC as a political party so it can carry on capturing the state.

If it were otherwise, he could start by showing some contrition and contempt for cadre deployment. It is the template for all of this.

It is worth asking what happens if you remove the Gupta family from South African politics? Indeed, what happens if you remove President Zuma, too? What are you left with? The answer, for those who wish to see it, is simple enough: a centralised, Leninist party that, in principle and policy, is dead set on capturing the state and has been going about its business in this regard by and large unfettered by anything other than its own incompetence.

If you have any beef with “state capture”, you would do well to consider cadre deployment first. If you cannot justify the one, you certainly cannot justify the other.