Protesters from Ennerdale, a suburb in the south of Johannesburg, burn tyres and barricade streets around the suburb during a violent protest over a lack of service delivery in the area on May 9, 2017. Picture: Tadeu Andre/AFP

HELESTI Daye-Fourie never leaves her house after dark. The risk of being carjacked and shot standing in her own driveway is too high.

Every day after picking up her eight-year-old son from school, the Johannesburg mum-of-two takes a different route home, eyes on the rear-view mirror. Her 20-month-old toddler sits in his car seat behind her, where he can easily be grabbed at a moment’s notice.

That’s because Ms Day-Fourie doesn’t want her son, in the event of an attack, to be trapped by his seatbelt, dragged along outside of the car and killed — as happened to a four-year-old boy whose parents and sister were forced out of their car by three armed men in nearby Boksburg, just 30 minutes away.

In Centurion, an hour’s drive away, a two-year-old was shot in the head during an attempted carjacking earlier this year.

“It makes us sound extremely paranoid, but this is how you need to live in South Africa if you want to stay safe,” she said. “Always cautious, always aware and always ready with an escape route. This is how we have to live, because s**t like this happens.”

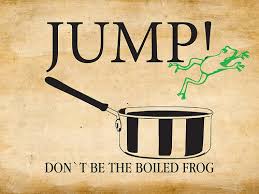

The 37-year-old, who works in digital marketing, said that she and most other South Africans were “so used to being frogs in the pot of boiling water that most days we don’t really realise how much is wrong with South Africa at the moment”.

“We have become so used to the daily instances of crime around us that we probably don’t even react to it anymore,” she said. “And that is the scary part. I guess if we had to react to what is happening around us, like ‘normal’ people would, we just won’t be able to function on a day-to-day basis.”

There has been rising racial violence in South Africa. Farmers in South Africa suffer more murders per capita than any other community across the world outside a war zone, and many are increasingly weighing their future.

But for the average family, the plummeting currency makes emigration unaffordable. Countries like Australia, the US and Canada accept a certain number of refugees each year, mainly through referrals from the UNHCR.

As of 2015, the UN body had about 112,000 registered refugees in South Africa, the majority from Somalia, the Congo and Ethiopia, with 899 resettlement submissions made in that year. For those wishing to come to Australia, the only other option is under the special humanitarian program, which requires a sponsor already here to apply on their behalf.

Ms Day-Fourie said most South Africans don’t want to leave, but for the sake of her children, “not considering emigration would be selfish”. She believes becoming a victim of violence is only a matter of time if they remain in the country.

She said the process of leaving “starts with a mind shift”. “We have a beautiful country and 85 per cent of the people are warm and loving. But bad things happen and becoming a victim of violent crime is not a case of if but when,” she said.

Johannesburg mother of two Helesti Daye-Fourie.Source:Supplied

“A few years ago, while walking in a park with my ex-husband, we were mugged. I fortunately got away without any injuries, but he was stabbed in the back trying to keep the two guys back while I ran looking for help.”

Ms Day-Fourie considers herself “extremely lucky” that this was the only time she had been a direct victim of crime. “But we are all on a daily basis indirectly victims of the crime around us,” she said. “None of us live a free life when you are always looking over your shoulder and locking up your house like Fort Knox the moment you walk in.”

Leaving, she said, is an expensive process with no guarantees, and the weak conversion rate makes it “almost impossible” for the average family. The language test required to apply for a visa alone will cost her more than a months’ worth of groceries.

“Most people just don’t have that much spare cash floating around,” she said. “So saving and planning takes a few years … and then when you think you are ready, immigration laws change.”

Another big issue is getting the required documents out of the chaotic South African bureaucracy such as birth and marriage certificates, which can take more than two years to arrive.

“It is also a very emotional decision,” she said. “You leave family behind. Elderly parents that will not get to see their grandchildren grow up. A life that you are used to. Customs and people that you are used to. And this is probably why Australia and New Zealand top most people’s lists as emigration options.”

Ms Day-Fourie said those who remain “want the world to know what is happening”, but said she didn’t think it was a case of being ignored, but rather the world “not realising how bad it actually is”.

“We ourselves also downplay it on a daily basis, not because we want to but to maintain some level of sanity,” she said. “Then there is also the sentiment towards white South Africans, that we deserve what is happening to us. We will be judged for actions of earlier generations whether we like it or not.

“I honestly want South Africa to survive. But she is killing herself because she cannot let go of the past.”

Roz Potgieter, 57, lives in Brisbane with her husband, a civil engineer, who arrived in the country on a 457 visa. She fears for her two adult children, who still live in South Africa.

“I was under the impression that with us coming over, once we became Australian citizens we would be able to bring our adult children over,” she said. “That’s how it used to be, but the Australian immigration system has changed drastically.”

Her children, who did not wish to be identified for this story, do not meet the “ridiculous criteria” set by the Immigration Department, Ms Potgieter said. “We don’t qualify for any benefits, we don’t want to go on the dole. We don’t have the dole in South Africa. We come here to contribute and work hard, to have a better life, a safer life.”

Ms Potgieter said those South Africans “fortunate enough to be living in Australia” with families back home “do not want our families ending up as disregarded statistics”.

“South Africa is a very, very violent country,” she said. “Outside of a war situation, it is the most dangerous country in the world. The statistics are frightening. One in three women in South Africa will be raped. My daughter has two little girls, a three-year-old and a six-month-old. If it’s not my daughter, it will be one of my granddaughters.”

Despite living like “Fort Knox”, her daughter’s home has been broken into three times in recent months. “There is nothing worse than living in fear, than going to bed at night thinking, ‘Am I going to wake up tomorrow in one piece?’,” she said.

Roz Potgieter’s two adult children are stuck in South Africa.Source:Supplied

She said she had a lot of family who are farmers who want to come over but can’t. “They all say, either they can’t afford it, or the immigration system is crazy — they don’t qualify for this reason or that reason.

“The only way we can come over is to pay large sums of money, and with the South African rand being so weak, our money gets divided by 10. Australia appeals to South Africans because it’s a very similar way of life, we love rugby and cricket, we all come from the same background.”

Ms Potgieter said letters pleading her children’s situation with Immigration Minister Peter Dutton were brushed off. She believes there is a case for persecuted South Africans to be granted a special intake under Australia’s humanitarian program, similar to previous one-off arrangements.

“There’s no problem with us assimilating into society, our backgrounds, our values, everything is exactly the same. We won’t drain the system, we are actually out to contribute.”

A spokeswoman for the Department of Immigration and Border Protection said 12 South African-born persons had been granted a humanitarian visa in the past five years, including both the onshore and offshore component of the humanitarian program.

The onshore component offers protection to people already in Australia, while the offshore component is split into the refugee and special humanitarian program (SHP) categories.

The refugee category “assists people who are subject to persecution in their home country and for whom resettlement is the best durable solution”. “Australia works closely with the UNHCR, which refers most of the successful applicants for resettlement in Australia under this category,” the spokeswoman said.

The SHP category is for “people who are subject to substantial discrimination amounting to a gross violation of their human rights and who are living outside their home country”, and must be sponsored by a person or organisation within Australia.

“Australia plays a leading role in global efforts to assist refugees and continues to rank as one of the top three resettlement countries each year, along with the United States and Canada,” she said.