New crime statistics show a slight drop in sexual offences but experts say true figures are much higher. The Daily Maverick asks if history can cure the crisis

Most South Africans learn about rape, or the threat of rape, when they are very young – even if they are yet to have the words for it. Sexual abuse has become normalised.

Though the country’s annual crime figures, released on Tuesday, saw the number of sexual offences drop by just over 5% to 53 617 between 2014–2015, most researchers believe this figure reflects only a fraction of actual that occur.

The chances of rape convictions have proved to be scanter still.

“I do not remember how old I was when I first became aware of rape as a thing in the world,” writes professor Pumla Dineo Gqola, who has made sexual assault the focus of her new book Rape: A South African Nightmare.

Understanding history

The notion that rape in South Africa is a specifically post-apartheid problem is dismantled by Gqola, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand.

It is natural that rape statistics would rise after 1994, she writes, because black women felt more comfortable to come forward. Police stations under apartheid had previously been deeply unfriendly places.

If we’re serious about tackling rape we must interrogate its histories properly, Gqola adds, taking into account the rape and forced impregnation of slave women in Cape society and that rape was a core feature of British colonial rule. Under apartheid, no white men were hanged for rape and the only black men who were hanged for rape were convicted of raping white women.

A history of violence and dispossession has bred a toxic masculinity at both ends of the political spectrum.

“Under colonialism and apartheid, adult Africans were designated boys and girls, legally and economically infantilised,” Gqola writes. Asserting masculinity could provide a way of rejecting that position.

Both sides were prone to hyper-masculinity – from the apartheid agents to the liberation figures, the struggle hero to the gun-toting Afrikaner.

Widespread perceptions about rape complicate the picture further: not all women are attacked by people they know; the abuse of children demonstrates that it is not all about sex.

There is no significant difference in the profile of those who rape adults and those who rape children, Gqola argues.

Nor is it about income. “I cannot accept the lie that poverty makes it more likely for men to rape,” Gqola writes, and her book profiles a number of cases involving wealthy, or relatively well-off men.

Female fear factory

According to Gqola the “female fear factory” keeps women silent and biddable.

Crimes like the rape and murder of Anene Booysen, 17, communicate a particular message to women: don’t go out at night, or that could happen to you.

“Even sports stars are unsafe,” says Gqola, referring to the gang-rape and murder of Eudy Simelane, a former midfielder for the national women’s football team Banyana Banyana.

Government gender initiatives in South Africa are superficial, she says: “‘The empowerment of women’, as currently employed and aired in South Africa, rests on the assumption that ensuring that some women have access to wealth, positions in government and corporate office.”

It proposes, she adds, that the public space is the only place in which women need to be empowered. This ignores domestic contexts, and the problem of violent masculinities.

We need to talk to young boys, Gqola argues, paying close attention to the lessons they absorbing about what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman.

Zuma on trial

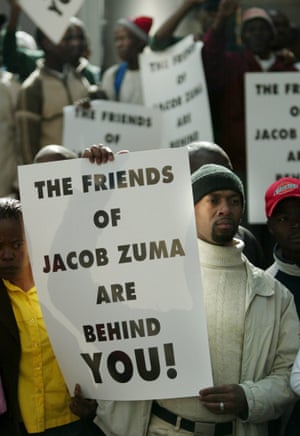

At the heart of Gqola’s book is the 2006 rape trial of Jacob Zuma: “a watershed moment” for South Africa’s gender problems.

The president was accused of rape charge by a woman known as Khwezi, a “well-known HIV-positive activist, lesbian daughter of Zuma’s late comrade”, who was forced to leave the country in the wake of the trial. Zuma, who was deputy president at the time, was acquitted by the courts.

Some aspects of Zuma’s trial were deeply typical. The media, for example, overwhelmingly focused their attention on the accused over the experience of his accuser.

Others were less so, due to the high profile of the accused: how quickly it was resolved; the fact that Khwezi was placed in witness protection; and the diligent collection of DNA evidence.

Gqola points to troubling aspects of the process, including Khwezi’s sexuality, which was dismissed and mislabelled as bisexual, and the fact that Khwezi’s previous sexual history was admitted into evidence in a bid to frame her as someone whom it would be “impossible to rape”.

A treatment, Gqola notes earlier in the book, also given to sex workers, wives, slave women and men.

Gqola’s book does not reach a definitive conclusion about South Africa’s rape crisis, but it does detail the social conditions which normalise and excuse it to this day.

“I wish that I did not have to think about rape, that it was not so close to home, that I did not have to think about the many times I have felt the combination of rage and tenderness as they talked about how someone had raped them” Gqola concludes.

But the South African public is better for her having done so.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/29/south-africa-rape-nightmare-crime-stats