THE Beny Steinmetz Group is perhaps the most successful, and controversial, diamond company you’ve never heard of. It’s the biggest buyer of diamonds from Anglo American’s diamond arm, De Beers, and a supplier to the luxury jewellery brand Tiffany & Co. But it is also a company that has been investigated by the US Federal Bureau of Investigations in six countries, and was accused of bribing Mamadie Touré, the wife of Guinea’s former dictator Lansana Conté, to score a $10bn iron concession in 2008 for $165m.

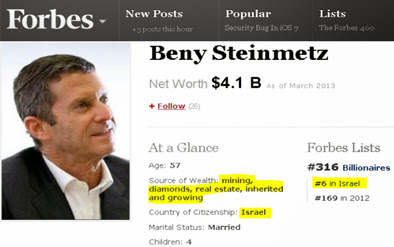

Given that profile, it’s no surprise that the group, started by the Israeli tycoon of the same name, has fought hard to avoid the spotlight. But, given an alleged tax avoidance scam in SA and an ongoing US grand jury probe into Guinea, Steinmetz hasn’t been able to avoid the headlines entirely.

Perhaps to mitigate this public glare, Steinmetz supposedly sold his 37.5% share in Steinmetz’s diamond segment, Diacore, to his brother, Daniel, in 2014.

However, leaked details from the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca, distributed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, suggest Steinmetz might not have actually stepped away from the business at all.

The leaked Panama Papers shed light for the first time on the labyrinthine structures Steinmetz put in place to distance himself from the business.

It’s a trail that also reveals much about why Africa’s west coast — despite being one of the most diamond-rich regions on earth — remains dirt-poor while companies like Steinmetz are minting it. And in many cases, these spoils get ferreted off to some secretive offshore tax haven.

In theory, Steinmetz’s only remaining involvement in the group’s diamond business is in Sierra Leone, through a company called Octea, which is registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), a tax haven.

Sierra Leone is still among Africa’s top diamond producers and Steinmetz (with an estimated personal fortune of $6bn) is the country’s largest individual investor.

Octea owns the Koidu mine in Sierra Leone. In theory, it is a moneyspinner. It is yielding gem-quality rough diamonds of $350/carat. And yet, the mine is also $150m in the red, with creditors queuing to be paid, including the government of Sierra Leone.

If it fails to pay its debt, Steinmetz risks losing his licence in the country. Sources in the country say this isn’t necessarily a problem, and that his plan is to feign financial problems, then make a run for it. (Steinmetz refused to answer questions about its financial practices, threatening legal action over issues he claimed were confidential.)

There are many questions about the mine: how are Koidu’s diamonds valued; why doesn’t Koidu’s data show tax payments; and why are the diamonds almost all exported to Switzerland, a tax haven notorious for re-exporting minerals?

There is, of course, some history to it. Back in 1995, the government of Sierra Leone entered into an agreement with Branch Energy, an arm of Executive Outcomes (EO), a mercenary outfit that assisted governments across Africa with “conflict”.

As payment for its services, the firm was given the mine. Then in 2003, the mine was transferred to Koidu, which fell under the Steinmetz Group, for a rumoured $28m.

EO’s Jan Joubert, self-described as the founder of Octea, was retained to continue running the Koidu mine. Sierra Leone’s government had a contract which spelt out the deal with Koidu: it would pay a $200,000 annual lease every year; income taxes of 35% would be deducted from Koidu’s net profit; and the government would impose an 8% royalty for exceptional diamonds valued at more than $500,000 per stone.

Now, the Panama leak shows a secretive financial structure connecting Koidu and Octea to wholly owned Steinmetz entities in Liechtenstein, the BVI and Switzerland. Some of these entities hold a great deal of money in comparison to Koidu.

In 2007, one of those companies, called Nysco, held $27.7m in a single HSBC bank account, while Koidu had only $5,401 in its HSBC account for the year. Beny’s brother Daniel was listed as the attorney for an HSBC bank account containing $250m.

The portrait painted is one in which Africa’s diamond profits — from Steinmetz’s operations in Namibia, Botswana, Angola and Sierra Leone — are spirited off the continent into offshore havens through shell companies. And yet at the same time, Koidu apparently can’t pay its bills. It owes over $150m in loans to Tiffany & Co and Standard Chartered bank. Neither of them responded to questions. What makes it even trickier is that Octea has more than half a dozen incarnations, Octea Limited, Octea Mining and Octea Technical Services among others, and are all incorporated in the BVI. It constantly shifts debt owed to Tiffany and Standard Chartered between the entities.

Koidu shouldn’t be in financial straits. Between 2012 and 2015, over 987,000 carats were exported out of Sierra Leone by Koidu at a value of more than $336m, based on mine-gate production value, not sales. For Sierra Leone, it’s a big deal, as Koidu’s exports amount to more than half its annual exports. Yet unlike other companies, Koidu’s taxes were never documented. During September 2015, for instance, taxes for all exporters except Koidu were registered, though it exported almost half ($9.5m) of all exports ($19.5m) during this month.

Sierra Leone’s National Mineral Agency did not respond to questions around these structures, taxes, profits or valuations.

For years, Sierra Leone’s diamond industry has been something of a black box. Until 2005, the government used a price book based on 1996 figures to value diamonds — which created an immense undervaluation.

However, the government uses a third party to check the pricing of diamonds, a company called Diamond Counsellor International (DCI). But according to a high-level source, that independent valuator may not be so independent after all. For one thing, sources claim DCI is allegedly contracted by a company called Infinite Diam, headed by Patrick Saada, who was with Steinmetz diamond group for 17 years, including a period as MD of Diacore. Infinite Diam also develops the marketing strategy for Octea’s rough diamonds. DCI has denied this claim, while Infinite Diam could not be reached.

DCI operates as government valuators in West African countries that are fraught with corruption. In Angola, for instance, the company is a principal adviser to the government, but Angola’s state-owned diamonds were subject to systemic undervaluation in collusion with diamond companies.

These undervalued diamonds were sent to tax havens, including Dubai, where they were valued at a higher price before being re-exported. DCI was also unceremoniously removed from Botswana and Namibia.

All of this paints a picture of a corrupted Sierra Leone diamond industry, seemingly for sale to the highest bidder.

Steinmetz’s Octea is arguably the most significant corporation in Sierra Leone’s diamond landscape, which is composed largely of artisanal miners connected to exporters through diamond buyers. In this equation, licensed diamond buyers or dealers purchase an undervalued rough stone from a “self-employed” miner before reselling it (or directly exporting) for the international market. Profit margins for these dealers can range between 30% and 100%. Companies like Koidu, which control the process of valuation in-house, are in the pound seats.

Quite how much profit Octea and Koidu make isn’t clear, because their accounts remain “confidential”. One source, who was once part of the Octea group, says he has no idea how it values its diamonds, nor why diamonds are exported to Switzerland.

There are also questions over whether Steinmetz really did hand over control of Diacore to his brother two years ago, thanks to the Panama Papers leak.

Diacore’s fiduciary agent is Mossack Fonseca. But the leaked documents suggest that in June 2015, Steinmetz asked Mossack Fonseca to backdate the transfer of his power of attorney to his brother to 2013.

The leaked data then shows how Mossack Fonseca and Diacore set about “erasing” the previous data. An e-mail dated June 24 2015 from Mossack Fonseca, damningly, is titled “PoA (power of attorney) backdated 2013” and says the law firm “knows very well the situation of Mr Beny Steinmetz.”

This was in response to Diacore’s request to “finalise the cancellation and back date the cancellation to the date mentioned in our initial request in 2013. The POA, dated 05/07/2007, was not only issued to Benjamin Steinmetz but also to Daniel Steinmetz and Marc Bonnant.” In a follow-up e-mail, Mossack Fonseca confirms to Diacore that it will consider backdating the power of attorney to remove Beny Steinmetz’s name and replace it with another.

What this episode implies is that this backdated power of attorney was a deliberate strategy for Beny Steinmetz to maintain control of the diamond business — and isn’t simply an accident, as Diacore claimed.

There are just as many questions over other shadowy entities, like a company called Onyx, which appears to be part of the Steinmetz group — though Steinmetz says it is an “independent and separate company”.

Onyx was instrumental in bribery in Guinea. A company owned by Onyx called Pentler facilitated payments to the president’s fourth and youngest wife, Touré.

In late 2013, Onyx’s office was raided by Swiss police in connection with Guinea.

The Steinmetz group denied involvement with Pentler, claiming rather it was created by a contracted employee named Fredric Cillins — who is now in prison for tampering with evidence proving the bribe.

Critics don’t buy that for a second.

Leigh Baldwin from Global Witness, the NGO that exposed the Guinea scandal, says that while the Steinmetz group claims Pentler was set up independently, the “close ties to Onyx show that claim is misleading”.

Pentler, Steinmetz directors and Onyx’s website registration list “BSGMS” as the registrant. In 2005, company records show it changed its name from “BSG Management Services” to “Onyx Financial Advisors”.

Then there’s Margali, an anonymous entity that has acted as director on many BSG entities including Koidu, Octea and myriad others. Says Baldwin: “Pentler was set up by Margali, a company linked to Steinmetz Group director Sandra Merloni-Horemans, throwing further doubt on any claim that Pentler was incorporated independently”.

As revealed in another Mossack Fonseca document, Cillins entered the picture on May 23 2007 as holding a power of attorney. Cillins’s power of attorney symbolises his representation of an unknown principal.

Steinmetz’s version of events is this: “Lacking a permanent presence in Guinea, [the group] sought to work with Noy, Ran and Cillins, who had extensive business operations in Guinea, which they subsequently established as Pentler Holdings.”

But not many people bought the view that Pentler was “independent”.

In 2014, Mossack Fonseca noted the US probe into Pentler and Steinmetz, and its lawyer recommended resigning immediately. The firm’s compliance department concluded of Onyx and the Steinmetz Group: “They are the same.”

These new documents link the Guinean bribes to Steinmetz and answer the question of how Africa’s resources wealth perpetually ends up elsewhere.

• This story was produced by the African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting in collaboration with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

http://www.financialmail.co.za/features/2016/04/14/panama-papers-bracelet-of-businesses