2017-06-04 06:02

President Jacob Zuma.

Tebogo Khaas

South Africa’s current economic woes can largely be blamed on the vagaries of globalisation and failure by the ANC government to implement its much-vaunted economic policies.

The country’s problems are, however, exacerbated by an organised conspiracy to raid its national purse by a few economic hit men aided and abetted by an impervious president.

Let me explain.

President Jacob Zuma has successfully ejected individuals considered a bulwark against his nefarious schemes from National Treasury and other key government institutions. He has created a cordon sanitaire necessary to enable his unimpeded pillaging of the national purse.

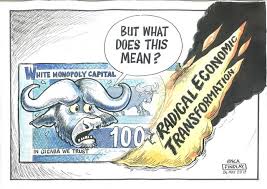

Recognising the intensifying national opprobrium that threatens to stymie his grand-theft scheme, Zuma and his apologists have sought to placate restless black voters by latching on to a chimerical concept called “radical economic transformation”.

This concept is designed to mask grand looting of state resources by Zuma, his cronies and economic hit men. In the meantime, the black economic empowerment project continues to falter.

In his international bestseller, Confessions of An Economic Hit Man, John Perkins describes economic hit men as politically exposed persons who raid and expatriate funds from developing countries’ national coffers with the tacit knowledge and connivance of the country’s rulers under the pretext of providing “much-needed” public infrastructure.

When these countries default on servicing debt incurred in fulfilling public projects, economic hit men call in their pound of flesh. They usually effect this by demanding concessions – on favourable terms – in respect of the country’s mineral resources or votes at crucial UN meetings.

Countries are therefore compelled to cede their sovereignty to foreigners who are financial benefactors of the president.

Economic hit men

South Africa’s economic hit men include the Gupta family and, ostensibly, Russian and Chinese oligarchs.

Although South Africa is unlikely, at least in the short term, to default on servicing its public debt obligations, limited public resources come under considerable strain to meet competing socioeconomic needs.

Zuma’s insatiable greed knows no bounds. He and his economic hit men are single-minded on cheating South Africa into undertaking large public projects solely designed to enrich themselves.

With the Gupta family’s alleged capture of the state, coupled with their proclivity to siphon funds illicitly derived from public projects to foreign jurisdictions; South Africa’s overreliance on imported capital-intensive public infrastructure; and procurement of grant-disbursement solutions from a foreign-owned entity, it is clear that Zuma’s version of “radical economic transformation” is not intended to advance genuine black economic empowerment.

As Zuma’s administration dithers from one corruption scandal to another, investor confidence continues to plummet. Whereas General Motors’ divestiture in the South African economy is reportedly due to normal global economic arbitrage, it is, however, feared that political instability in the country may have also contributed to its decision to leave. It is likely that further divestments by other multinationals and attendant capital outflows may follow.

While General Motors’ departure is regrettable, this – fortuitously – presents an opportunity for South Africa to accelerate investment in its own high-tech motor manufacturing capabilities just as South Korea, Malaysia and China have successfully done.

Insatiable demand for safe, reliable and affordable public transport (for example, minibus taxis and integrated bus-rail transit systems) presents an opportunity for the emergence of genuine black industrialists who could successfully compete with established foreign manufacturers in local and foreign markets.

Also, assuming there is justification for a nuclear build programme, there seems to be no reason why local black industrialists could not be afforded the opportunity to acquire the necessary technical know-how to build the plant. This is particularly compelling given the disclosure that the ill-fated memorandum of understanding South Africa had with Russia would have freed Russia from any technical and financial risk associated with the project.

A president with a simple plan

South Africa has, in the past, shown that – with the necessary political will and support – black entrepreneurs are capable of undertaking projects considered high-tech. In the early 2000s, Telkom successfully commissioned a local black-owned company to manufacture and supply millions of chip-based telephone cards. This was a country-first as Telkom had, before then, imported all its phone cards from France.

Today, South Africa boasts a world-class smart card manufacturing industry capable of meeting demand for smart cards by the banking, telecommunication and government sectors.

For South Africa to prosper, it needs to choke public corruption on whose prevalence economic hit men and politically exposed persons thrive. It also needs a government that will doggedly implement its much-vaunted economic policies and foster a thriving local manufacturing sector.

The current political climate and the ANC’s repeated prevarication on reining in its errant president does not, however, bode well for the country’s economic prospects.

South Africa has a president with a simple plan: plunder the scarce resources of the country by any means necessary and, as suspected, flee the country in order to escape accountability after repatriating ill-gotten gains offshore.

This is what raises most South Africans’ collective temper.

One of former president Nelson Mandela’s few displays of temper, aimed at then president FW de Klerk, came at the end of the first day at Codesa when he addressed the plenary thus: “Even the head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime, as his [De Klerk’s], has certain moral standards to uphold.”

I was tempted to appropriate Madiba’s words and appeal to Zuma – head of an inept, discredited majority regime – to accede to his compatriots’ clamour for him to gracefully step aside.

But then I realised that, unlike Zuma, at least De Klerk had a conscience that Madiba could appeal to.

Khaas is a political commentator and executive chairman of Corporate SA, a Johannesburg-based strategic advisory consultancy. Follow him on Twitter @tebogokhaas