The series of clashes historically known as, Frontier Wars date back to 1779 whenXhosa people, Boers, Khoikhoi, San and the British clashed intermittently for nearly a hundred years. This was largely due to colonial expansion which in turn dispossessed Xhosa and Khoikhoi people of their land and cattle among other things. Although periods between the wars were relatively calm, there were incidents of minor skirmishes sparked by stock theft. In addition, alleged violations of signed or verbal agreements played a vital role in sparking the incidents of armed confrontations. Colonists also sought to consolidate their gains through the presence of military force as witnessed in the building of forts, garrisons, military posts and signal towers. Resistance from particularly the Xhosa was a cohesive one; other Xhosa ethnic groups cooperated with the colonial government when they felt doing so would advance their own interests.

Early History of the Eastern Cape

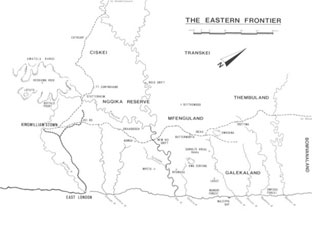

Map of the Eastern Frontier. Source: samilitaryhistory.org[Accessed: 25 January 2012]

Map of the Eastern Frontier. Source: samilitaryhistory.org[Accessed: 25 January 2012]

During the early years before Dutch occupation of the region, the Xhosa, Khoikhoi and San people focused primarily on hunting, agriculture and stock farming. In the 1700s, the lack of sufficient space for proper stock farming forced the farmers to pack their possessions into their ox wagons and move deeper into the interior of the Cape Colony. These farmers were called a “Trek boers” (Migrant farmers).

Until 1750 (29 years before the First Frontier War), migrant farmers rapidly advanced rapidly into the interior using force. For instance, the use of superior weapons such as guns quickly subdued resistance from local people. Those people who were subdued and those submitted to Trek Boers as an attempt to protect their livestock and land were employed to tend to the cattle and provide other labour needs of the white famers. However, the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.) became worried about the migrant farmers moving so far because it became increasingly difficult to exercise any authority over them.

In order to maintain its authority, the V.O.C. was forced to follow in their tracks. This constant moving also resulted in the V.O.C. having to continually change the boundaries of the eastern part of the Cape Colony. Eventually, in 1778 less than a year into the First Frontier War, the Great Fish River became the eastern frontier. It was also here that the migrant farmers first experienced problems with the Xhosa.

Until that time, the migrant farmers had only experienced serious clashes with the San people when the San attacked them with poisoned arrows and hunted their cattle. The migrant farmers frequently organised hunting parties in reprisal for the San attacks. When the frontier farmers, as they were now called, met with the Xhosa, serious clashes broke out. Each group felt that the other was intruding on their territory and disrupting their livelihood, and both wanted to protected themselves at all costs.

The V.O.C. established new districts such as Swellendam and Graaff- Reinet in order to maintain authority over the frontier and to quell the ongoing violence, but to no avail. The frontier farmers kept on moving across the border and the Xhosa vigorously resisted this incursion. A number of wars followed as both groups fought each other over territory and resources.

The chronology of all nine Frontier Wars is briefly discussed below:

First Frontier War (1779-1781)

It is widely believed that the First Frontier War which broke out in 1779-1781 was really a series of clashes between the Xhosas and Boers. Around 1779, allegations of cattle theft by Xhosas had become so common on the south-eastern border, forcing the Boers to abandon their farms along the Bushmans River. Subsequently, in December 1779 an armed clash between Boers and Xhosas ensued, apparently sparked by irregularities committed against the Xhosa by certain white frontiersmen.

In October 1780 the Government appointed Adriaan van Jaarsveld, a highly experienced commando leader, to be field commandant of the whole eastern frontier, and a commando led by him captured a very large number of cattle from the Xhosa and claimed to have driven all of them out of the Zuurveld by July 1781.

Second Frontier War (1789-1793)

This led to considerable bitterness among the eastern frontiersmen, particularly since war among the Xhosas in 1790 increased Xhosa penetration into the Zuurveld, and friction mounted. In 1793 a large-scale war was precipitated when some frontiersmen under Barend Lindeque, including the lawless Coenraad de Buys who had previously been involved in outrages against the Xhosa, decided to join Ndlambe, the regent of the Western Xhosas, in his war against the Gunukwebe clans who had penetrated into the Zuurveld. But panic and desertion of farms followed Ndlambe’s invasion, and after he left the Colony his enemies remained in the Zuurveld.

Farmers developed the technique of a laager for defence at Zuurveld.Source: newhistory.co.za[Accessed: 26 January 2012]

Farmers developed the technique of a laager for defence at Zuurveld.Source: newhistory.co.za[Accessed: 26 January 2012]

In spite of the fact that two Government commandos under the landdrosts of Graaff-Reinet and Swellendam penetrated into Xhosa territory as far as the Buffalo River and captured many cattle, they were unable to clear the Zuurveld, peace was made in 1793. Frontier discontent over Government policy precipitated revolts in Graaff-Reinet and Swellendam in 1795.

Although the northern part of the Zuurveld was re-occupied by Boer farmers by 1798, many Xhosa clans remained in the southern Zuurveld area, some even penetrating into Swellendam, partly as a result of a civil war between the followers of Ndlambe, the acting regent of the Western Xhosas, and his nephew Gaika, the legitimate heir. The Government found it impossible to persuade the Xhosa clans in the Colony to go back across the Fish River. Stock theft and employment of Xhosa servants increased tensions, and in January 1799 a second rebellion occurred in Graaff-Reinet. This precipitated the Third Frontier War (1799-1803).

Third Frontier War (1799-1803)

In January 1799 a second rebellion occurred in Graaff-Reinet necessitating the Third Frontier War. In March of the same year, Government of the First British Occupation sent some British soldiers under Gen T P Vandeleur to crush the Graaff-Reinet revolt. No sooner was this done (April 1799) than some discontented Khoikhoi revolted, joined with the Xhosa in the Zuurveld and began attacking white farms, reaching as far as Oudtshoorn by July 1799. Vandeleur’s force on its way back to Algoa Bay was attacked by a Gqunukwebe clan, fearing expulsion from the Zuurveld. Commandos from Graaff-Reinet and Swellendam were mustered, and a string of clashes ensued.

The Government dreaded a general Khoi rising, and so made peace and allowed the Xhosas to remain in the Zuurveld. In 1801, another Graaff-Reinet rebellion began, forcing further Khoi desertions. Farms were abandoned en masse, and the Khoi bands under Klaas Stuurman, Hans Trompetter and Boesak carried out widespread raids. Although several commandos took the field, including a Swellendam commando under Comdt Tjaart van der Walt, who was killed in action in June 1802, they achieved no permanent result. Even a ‘great commando’ assembled from Graaff-Reinet, Swellendam and Stellenbosch could not make any real headway.

In February 1803, just before the British government handed over the Cape Administration to the Batavian Republic, and an inconclusive peace was arranged. The Batavian authorities propitiated the resentment of the eastern-frontier Khoi-khoi but could not persuade the Xhosas to leave the Zuurveld (1803-1806).

Fourth Frontier War (1811-1812)

The Fourth Frontier War was neither the direct or indirect consequence of the anger emanated from the three previous frontier wars and the violation of the agreements that declared the Zuurveld region a ‘neutral ground’. Ignoring the agreement, the Xhosas occupied the ‘neutral ground’, an act that prompted the Cape government in 1809 to send Lt-Col Richard Collins to tour the frontier areas. After touring the areas he recommended that the Xhosa be expelled from the Zuurveld, which should be secured by dense white settlement, and that the area between the Fish and the Keiskamma Rivers be unoccupied by black or white. Many historians believe that the Fourth Frontier War came as a surprise to the Xhosa as the opposition troops were well prepared, unlike in three previous encounters.

The British Army charging the enermy at Zuurveld. Source: www.bedford.co.za[Accessed: 25 January 2012]

The British Army charging the enermy at Zuurveld. Source: www.bedford.co.za[Accessed: 25 January 2012]

In 1811, Colonel John Graham took the area with a mixed-race army. Subsequently, in January and February 1812, 20 000 Gqunukwebes and Ndlambes were driven across the Fish River by British troops in conjunction with commandos from Swellendam, George, Uitenhage and Graaff-Reinet under the overall command of Lt-Col John Graham. On the site of Colonel Graham’s headquarters arose a town bearing his name Grahamstown. It is one of the first towns to be established by British in South Africa. Post the war, a line of frontier forts was built to hold the frontier, but an attempt to establish a dense Boer settlement behind them botched. Consequently the Governor, Sir Charles Somerset, made a verbal treaty with Gaika, the supposed paramount chief of the Western Xhosas. Unfortunately this agreement between Sir Charles Somerset and Gaika helped provoke a quasi-nationalist movement among the Western Xhosas, led by the ‘prophet’ Makana, which led to a renewal of the civil war between Gaika and Ndlambe. During the Fifth Frontier War (1818-1819), Lt-Col John Graham never had a direct role as he was at Simonstown where he was a commando.

During the dying phase of the Fourth Frontier War, Piet Retief and three commandants of the new Stellenbosch commando went to relieve serving burghers on the eastern frontier. At the end of 1813 Retief moved to the eastern districts, where he married the widow Magdalena Johanna Greyling.

Fifth Frontier War (1818-1819)

Following Gaika’s defeat at Debe Nek in 1818, he asked the Cape for help. Subsequently, colonial forces invaded Xhosa territory in December 1818 and triumphed over Ndlambe’s warriors. When they left, however, Ndlambe was again able to defeat Gaika, and then continued into the Colony and attacked Grahamstown in April 1819. The attack was repulsed, and Cape forces defeated Ndlambe and marched as far as the Kei River.

In October 1819 the Xhosa chiefs were obliged to recognise Gaika as paramount chief of the Western Xhosas, and he and Somerset made a verbal treaty that provided that the whole area between the Fish and the Keiskamma Rivers, except for the Tyume Valley, which remained Xhosa territory, should be a neutral zone closed to both black and white occupation. Behind the Fish River, the 1820 Settlers were established in the Zuurveld in an attempt to provide the dense white settlement that alone could make a frontier line viable.

Sixth Frontier War (1834-1835)

By early 1830s the line of clashes had spread to the Keiskamma River, now regarded as the Cape’s eastern frontier. Segregation had broken down. Whites, Khoikhoi and Xhosas lived in the ‘neutral’, now significantly called the ‘ceded’, territory, and trade and employment were permitted. Insecurity persisted. The effective extension of the Cape frontier to the Keiskamma River increased overcrowding among the Xhosas beyond, already subject to considerable pressure from other tribes displaced by the Zulu empire. The Government pursued a vacillating policy towards allowing Gaika’s sons to occupy land in the Tyume Valley.

In 1829 Maqoma and his tribe were expelled from the Kat River area (where Khoikhoi were settled) and settled on inferior land farther east, but were allowed to return to the Tyume Valley in 1833, to be expelled again almost immediately. Tyali and Botumane (‘Botma’), other Gaika chiefs, were treated in a similar fashion. In 1834 the British government instructed Sir Benjamin D’Urban to institute a civil defence system supplemented by treaties with chiefs paid to keep order and advised by Government agents. Before this could be done, the bitterness aroused by the renewed expulsion of Maqoma and Tyali from their Tyume lands in 1833 was exacerbated by drastic reprisals by colonial patrols as a result of increased cattle theft by Xhosas during a period of drought.

On 31 December 1834 a large force of some 12 000 Western Xhosas – led by Maqoma, the regent of the Gaika Xhosa tribe, Tyali, other Gaika chiefs, as well as some clans belonging to the Ndlambe branch – swept into the Colony. Raiding parties devastated the country between the Winterberg and the sea. Piet Retief managed to defeat them in the Winterberg, and Lt-Col Harry Smith was immediately sent on his historic six-day ride from Cape Town to Grahamstown to take command of the frontier. Reinforcements were sent by sea to Algoa Bay and burgher and Khoi troops were called out.

After a series of engagements, including that of Trompetter’s Drift on the Fish River, the chiefs fighting between the Sundays and Bushmans Rivers were defeated, while the others (Maqoma, Tyali and Umhala) retreated to the fastnesses of the Amatole Mountains. D’Urban arrived at the frontier on 14 December 1834. He believed Hintsa, the chief of the Eastern Xhosa (Galekas) and presumed paramount over the whole Xhosa nation, to be responsible for the attack on the Colony, and held him responsible for the theft of colonial stock captured during the invasion.

Therefore D’Urban led a force of colonial troops across the Kei to Butterworth, Hintsa’s residence, and dictated terms to him. They comprised the annexation of the area between the Keiskamma and Kei Rivers as British territory (to be called Queen Adelaide province) and the expulsion across the Kei of all tribes involved in the war. Queen Adelaide would be settled by loyal tribes, by rebel tribes who disowned their chiefs and by Fingos, remnants of tribes who had been destroyed by the rise of the Zulu empire and who had hitherto been living in Hintsa’s territory under Xhosa subjection.

However, expulsion of the undefeated Xhosa from Queen Adelaide proved impossible, so in September 1835 D’Urban made treaties with the ‘rebel’ chiefs, allowing them to remain in locations there on condition of good behaviour as British subjects under the control of magistrates who, it was hoped, would rapidly undermine tribalism with missionary help. But territorial expansion contradicted British desires for economy, and the British government, doubtful of the justice of the war and ignorant of the details of D’Urban’s actions because of his long delays in sending explanations, disannexed Queen Adelaide. New treaties made the chiefs responsible for order beyond the Fish River (December 1836).

Seventh Frontier War (1846-1847)

The Seventh Frontier War (‘War of the Axe’) began in March 1846 with the defeat at Burnshill of a colonial force under Col John Hare. The Colonial force invaded Xhosa territory following the ambush of a patrol sent to arrest a Xhosa accused of stealing an axe. The Xhosas retaliated by invading the Colony and carrying off large numbers of cattle. Although the Mfengus (Fingos) cooperated with the colonial forces, who were able to defeat the Xhosas at the Gwanga (June 1846), drought hampered the movement of troops, and the attempt to defeat the tribes in the Amatole Mountains (July/August 1846) proved unsuccessful.

Allegedly a Xhosa man stole an axe and that sparked the war.Source: www.dipity.com[Accessed: 26 January 2012]

Allegedly a Xhosa man stole an axe and that sparked the war.Source: www.dipity.com[Accessed: 26 January 2012]

However, burgher forces under Sir Andries StockenstrÁ¶m pushed into the Transkei forced Kreli, the Gcaleka chief, to acknowledge responsibility for the attacks of the Gaikas, restore the stock captured in the war and surrender all land west of the Kei. But the war was not yet over. Its end was delayed by drought, which hampered the movement of colonial forces, by quarrels between the burgher forces and the regular troops, and by the fact that several tribes remained undefeated and able to conduct guerrilla operations, despite the ‘scorched earth’ tactics of the Cape forces. Only in December 1847 did the last chief submit.

Eighth Frontier War (1850-1853)

In October 1850 Sandile, the principal Gaika chief, was deposed for refusing to attend a meeting of chiefs called by the Governor, subsequently, on 24 December the Gaikas attacked a colonial patrol at Boomah Pass and destroyed three military villages. The Gaikas received support from the Thembus and some Gcalekas. They were later joined by some rebellious ‘black police’ and some Khoikhoi from the Kat River settlement under Hermanus Matroos and Willem Uithaalder.

The Khoi revolt undoubtedly helped to keep the momentum of the war, since the Khoikhoi were experienced in white fighting methods. Military camps such as Fort Beaufort (January 1852) were attacked and caused the Government constant anxiety as to the loyalty of its Khoi auxiliaries. The Kat River revolt also meant that the burghers of the eastern districts did not respond to the call to commando duty, while only 150 burghers from the western areas had gone to the front by February 1851.

Towards the end of February 1851, The Kat River rebellion was crushed. Meanwhile Comdt Gideon Joubert began the attack on the rebel Thembus, and a combined force of Thembus and Gcalekas was defeated on the Imvani River by Captain V Tylden in April 1851. Although the Government enjoyed the support of the Mfengus, most of the Ndlambe tribes and a large number of Khoikhoi, its operations were hampered by the paucity of regular troops. For the first time the Gaikas and their allies were using firearms. In addition, fighting was also going on against the Basuto in the Orange River Sovereignty. All these factors contributed to delay the end of the war.

The Waterkloof valley one of the battlefields during Eight frontier War.Source:www.molweni.com [Accessed: 26 January 2012]

The Waterkloof valley one of the battlefields during Eight frontier War.Source:www.molweni.com [Accessed: 26 January 2012]

By early 1852, Sir George Cathcart arrived at the Cape to replace Sir Harry Smith. Under his command the war was vigorously pursued to its close. A combined force of regular troops, under Generals H Somerset and V Yorke, continued a previous operation started in December 1851 and defeated Kreli. In September 1852 the Amatole region had been cleared of Gaikas, and by November the last Khoi rebels had been defeated.

In the new settlement, the rebellious tribes were moved out of the Amatole Mountains to locations in British Kaffraria and their lands given to white settlers. Shortly after, Sir George Grey’s vigorous attempt to break down tribalism in British Kaffraria aroused the ‘cattle-killing movement’ among the Xhosa ethnic groups on both sides of the Kei (1857) and left the Kaffrarian Xhosas destroyed. British Kaffraria was incorporated into the Cape in 1866.

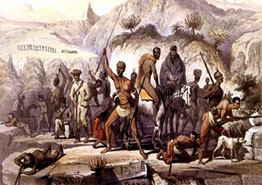

Xhosa warriors during the Eight Frontier War. Source: www.ezakwantu.com [Accessed: 26 January 2012]

Xhosa warriors during the Eight Frontier War. Source: www.ezakwantu.com [Accessed: 26 January 2012]

In 1858 Sir George Grey, convinced of Kreli’s complicity in the cattle-killing episode, sent an expedition to drive the Gcalekas beyond the Bashee River into Bomvanaland. The vacated Transkeian territory was at first administered as a dependency of British Kaffraria, and annexed to it in March 1862. Locations were established there, for Mfengus at Butterworth, and for some Ndlambes at Idutywa. But the British government felt it would be too expensive to hold this new frontier, so disannexation back to the Kei occurred in 1864.

Ninth Frontier War (1877-1878)

Kreli was allowed to return to the Transkei, but the Gcalekas were forced to share their old lands with the Mfengus, whom they despised. In August 1877, when tensions were high between the two tribes, a quarrel arising at a Mfengu wedding party provoked the Ninth (and last) Frontier War. The Cape Frontier Police under Col Charles Griffith crossed the Kei with a volunteer force to protect the Mfengus, and with the aid of the Thembus and Mfengus pushed the Gcalekas beyond the Mbashe River (September 1877). But Sir Bartle Frere, the High Commissioner, overthrown Kreli, and decided that Galekaland should be settled by whites and the Gcalekas disarmed once and for all.

One minor Gcaleka clan was chased into the location of Sandile, the Gaika chief. The Gaikas fired on the police, were joined by the Gcalekas in an attack on the Colony and gained support from the Thembus. The war provoked a constitutional crisis at the Cape, which had received responsible government in 1872. The Cape ministry under Molteno insisted that the combined force of regular troops, colonial police and volunteers be under the full command of Comdt Gen Griffith. Sir Bartle Frere insisted that he, as Imperial Commander-in-Chief, take charge of the conduct of the war, subsequently; he dismissed the Molteno cabinet, appointing a new ministry under Gordon Sprigg in its place.

The ninth war was soon over. In February 1878 Kreli’s forces were defeated at Kentani, and Kreli surrendered in June. By then Sandile had died and an amnesty was granted to his followers. In 1879 Mfenguland and the Idutywa district were annexed to the Cape, and Gcalekaland, though not formally annexed, was administered by the Cape under the chief magistrate of the Transkei. By 1894 the boundaries of the Cape had been peacefully extended to the Mtamvuna River by the piecemeal annexation of the remaining nominally independent tribal areas.

• My Fundi, ‘Pieter [Piet] Retief (1780-1838)’, [online], Available at www.myfundi.co.za [Accessed: 25 January 2012]

• Grahamstown, ‘The Frontier Country’, [online], Available at www.grahamstown.co.za [Accessed: 25 January 2012]

• Maclannan B., ‘A Proper Degree of Terror: John Graham and the Cape’s Eastern Frontier’, African Affairs, Oxford Journals, pg 307.

• My Fundi, ‘Eastern Cape Frontiers Wars II Timeline’, [online], Available at www.myfundi.co.za [Accessed: 25 January 2012]

• Gon P. ‘The Last Frontier War’ The South African Military Society, Military History Journal Vol 5 No 6, December 1982.

Last updated : 10-Feb-2012

This article was produced for South African History Online on 21-Mar-2011

http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/conquest-eastern-cape-1779-1878