Essay |

Chronicle #11 / By Evelyn Groenink

Clive Derby-Lewis, co-conspirator in the murder of South African freedom struggle hero Chris Hani in 1993, was once again denied parole, for the third time, in January this year. Whilst Chris Hani’s family and many old friends and comrades applaud the decision to ‘let him rot’, some ask how much Derby-Lewis actually knew about the murder. One of these voices is Evelyn Groenink, who investigated the Chris Hani murder case -and several others- for years. Her research, which unearthed arms trade links to both the Hani and September murders, was published only in the Netherlands, in a language largely foreign to the international community. The history of a story that could not be told.

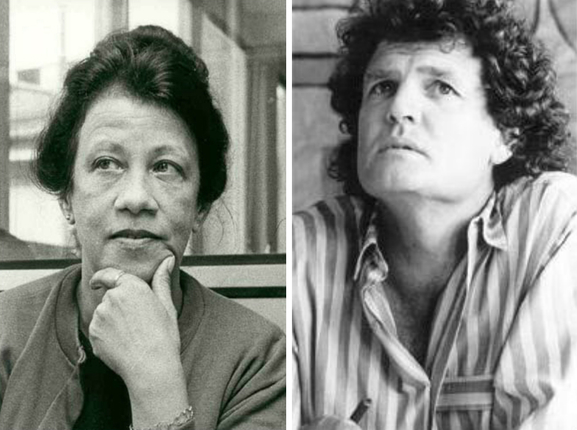

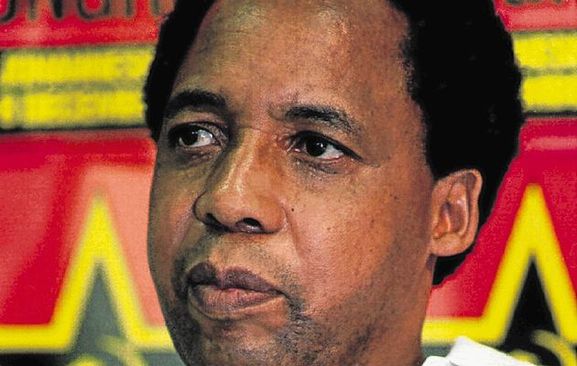

ANC representative Dulcie September was killed in Paris in 1988, when talks about future arms contracts between France and the ANC were on the agenda; SWAPO- man Anton Lubowski, ditto, in front of his Windhoek home in 1989, shortly after befriending an arms- and diamonds dealer; and the ANC’s beloved Chris Hani was murdered in 1993 (one year before the first democratic elections in South Africa), in the midst of massive bribe-offering by arms dealers to key people in the ANC military.

In all three cases, I was told by people close to the victims that they had been ‘obstacles’. Dulcie September had been “fighting with important people.” Lubowski “had not wanted to do what [certain businessmen] wanted.” Hani “would not allow the corruption of the ANC’s guerrilla army,MK” In the late eighties and early nineties, when South Africa and neighbouring Namibia transitioned from apartheid rule to democracy and sanctions were lifted, dozens of international businessmen had flocked to the impending new ANC and SWAPO governments to buy up resources and sell arms.

In Namibia, Namibian, French, Italian, Israeli and American diamond buyers had entered the post-sanctions scene and arms dealers started approaching the ANC in South Africa as early as 1991.

September, Lubowski and Hani had objected to, respectively, a nuclear military technology exchange; a set of oil-, diamonds- and casino rights deals; and the now notorious South African arms deal. I wrote about these things, in Mail & Guardian and elsewhere.

Official police investigations identified all three murders as motivated by apartheid hate and perpetrated by death squads or (in the case of Hani) right-wing extremists. This official narrative is still dominant in South Africa: puzzlingly so, considering that, in two of the three cases, high ranking ANC- and SWAPO officials have suggested that the truth should indeed be sought on the terrain of shady contracts. Former ANC deputy minister of foreign affairs, Aziz Pahad, is on record confirming that “Dulcie [September] stumbled on nuclear issues”. SWAPO’s Haage Geingob told a journalist that Anton Lubowski, on the day of his murder, was sorting out highly sensitive ‘financial matters’.

In the case of Chris Hani, former comrades explained to me how he was an obstacle to the USD$ 60 million arms deal that was being negotiated with others in the ANC leadership at the time. From the police docket in the case, I found that a crucial part in the Hani murder was played by Peter Jackson, a chemicals transporter with arms trade connections, who was the employer of Hani’s convicted murderer Janusz Walus, and who seemed to have been telling Walus what to do. The police had been kept from investigating Peter Jackson by a written instruction from the Security Police that read: “Inligting oer Peter Jackson sal nie opgevolg word nie”.

All this, I published. But only in Dutch, never in English: the South African publication was prevented through legal and physical threats to the publisher. In alecture for the University of the Witwatersrand, Jacana publisher Maggie Davey questioned the reasons why she was unable to publish. “These questions are […] about how truth can be covered up and how the interests of a few powerful constituencies can shift and shape our understanding of history”.

I published several stories

I published several stories about the arms deal – and mafia links to the Dulcie September and Anton Lubowski murders in the South African Mail & Guardian. The full story of all three murders and their ‘dodgy deals’ background was told in my book ‘Dulcie, a woman who had to keep her mouth shut’ published in 2001, in Dutch, in the Netherlands – the same book that Jacana’s Maggie Davey had wanted to publish in South Africa. (An unpublished translation of the book was made available in South Africa to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the South African ‘FBI’, the Scorpions.) The Anton Lubowski story was captured in a South African investigative journalism training manual; the Dulcie September investigation was published in the Rhodes Review (of Rhodes University in Grahamstown, also South Africa) and the story about the arms trade links in the Chris Hani case was published in ZAM Magazine in the Netherlands in 2005. But, strangely, every time the stories are published, or discussed, they fall into a big silence. The pattern is usually the same. I publish, there are some responses (like a police force pledging to reopen the case), one interview with a newspaper or radio station, then – nothing. After a while, every single darn time, the official narrative is back. In 2010, eleven years after I first published the first September and Lubowski stories in Mail & Guardian, the Dulcie September memorial lectures at the University of the Western Cape reverted neatly back to the ‘extremist death squad’ story.

In 2011, the repeated admission by former foreign minister Aziz Pahad that September was killed over ‘nuclear issues’ (first made to me in 1995 and now re-recorded by a French investigative documentary maker) made it again to Mail & Guardian. Nevertheless, the Cape Times in 2012 again only spoke of ‘apartheid death squads’ as the culprits. The story ‘The Lubowski files’, published prominently by Mail & Guardian in 1999, cannot even be found on their website anymore.

‘The world is a dangerous place, you know’

In the case of the Chris Hani investigation, South African publisher Jacana was made to fear bankruptcy by arms dealers’ lawyers, some of whom threatened expensive pre-publication litigation. Military vehicles dealer Witold Walus, brother to Janusz Walus, sued for real.

Violence was threatened by NIA operative Michael Buchanan, who said he would ‘klap’ me, and ‘beat up’ the publisher. Interestingly, Buchanan also said he would ‘bring Gerrie Nel and the Scorpions’, with whom he said he had a good relationship. (If so, it might explain why Gerrie Nel, in spite of a promise to take up the Hani case again, never did.)

Then there was former foreign minister Pik Botha, who was so upset about the claims by some sources that he had been party to arms deals, that he kept phoning Jacana for hours at the time, explaining how only a ‘sick, perverse and criminal mind’ could think such things. During one of these phone calls he also told Jacana’s Maggie Davey sternly that ‘the world is a dangerous place, you know.’

As a result, all that most South African citizens know about the Chris Hani murder, is that two right-wingers, Polish immigrant Janusz Walus and ultra-conservative former Mayor of Krugersdorp, Clive Derby-Lewis, are to blame. The two are still in jail. There is a massive popular outcry every time even a mention is made of amnesty or health parole.

So why not simply give up and accept the official dominant narrative? Nothing will bring the dead back to life. And why not blame apartheid and racists? There was apartheid, there still are violent racists, and both have inflicted trauma on South Africa and the world. What does it matter if they are blamed for a few more things?

It matters, because the story of freedom fighters who stumbled upon corruption and wanted to stop it is worth telling. The African continent is often perceived as endemically corrupt. How can that perception change if stories such as these are silenced? I recall a young woman in Cape Town, who, after I spoke about my book to a small audience, looked at me almost reproachfully and asked: “But where is that book? I want to read that book!”

So here it goes, one more time.

‘I want to read that book’

Dulcie September had been on the trail of nuclear military technology exchanges between France and the South African government. She had had meetings with sources in the arms trade whom she kept secret even from her private secretary, had phoned the highest regions in the ANC to come and stop what was going on, had planned to inform the anti-apartheid arms sanctions campaign, and had been shot, very professionally, five times in the head, before she could go any further. Aziz Pahad had confirmed to me, in 1995, that she had “stumbled on nuclear issues”. All this had been published in 1998 in the Mail & Guardian.

There was a ripple in the silence following this article when Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigator, detective Jan Ake Kjellberg (who had been seconded to the TRC by the Swedish government) tried to take the matter further. However, right after he had gone to France to follow up on the arms deal trail in the Dulcie September case, he was fired and sent home to Sweden. Kjellbergs reports are contained in boxes that have been moved to the National Intelligence Agency’s custody, where they remain inaccessible to the public to date.

The same arms wheeler dealer whom Kjellberg and I had investigated in the Dulcie September case had befriended SWAPO-man Lubowski a few months before his murder. The arms dealers’ name was Alain Guenon. He had high-profile links with the presidential Mitterrand family in France and had also, posing as a socialist supporter of ANC and SWAPO, managed to become an advisor to the ANC’s Winnie Mandela and Tokyo Sexwale. Another ‘friend’ who had become close to Anton Lubowski at more or less the same time as Guenon was Vito Palazzolo, the Italian banker sought by Italian (and other) authorities for mafia-links and money laundering.

Casino rights

Unbeknownst to Anton Lubowski however, Guenon, and Palazzolo knew each other: they were later identified by the international research agency Kroll as long standing business partners in a diamond mine in Angola. Both were (also secretly) good friends of the rogue, smuggling, apartheid military establishment.

Guenon was linked to Military Intelligence’s Directorate for Covert Collection (DCC) through a joint partnership with the DCC’s operative Rob Colesky in a front company in Namibia, Spectrum Furniture. The company was selling furniture to SWAPO for their new government offices. It was this furniture deal that came with a ‘facilitation fee’ for Lubowski, in cheques that were later proven to originate from South Africa’s military intelligence.

According to two independent sources in Windhoek, the ‘facilitation fee’ was at the core of the financial issues that Lubowski was ‘sorting out’ on the day of his murder. Friends of Lubowski also confirm that Palazzolo and Guenon had demanded that the SWAPO advocate deliver certain business contracts in the fields of casino rights, diamonds, and oil transport to them. They report that Lubowski had told them, in distress, that he “didn’t want to do all that these people wanted from him”. But how to say no, when he had already accepted their – later shown to be tainted – money?

Still, Lubowski worked the entire day of his murder on the books that contained entries related to the ‘facilitation fee’ he had accepted, and he told his comrade, fellow SWAPO-leader Haage Geingob, in a very private conversation about the ‘financial issues’. It was at the end of this day, after the DCC’s Rob Colesky had visited his house to ask what time Lubowski would be home, that ‘the people’s lawyer’ was shot dead in his front yard. Colesky would later surface again as a fellow director inseveral of South African arms deal middleman John Bredenkamp’s companies.

The TRC attributed both the September and Lubowski murders to an apartheid ‘death squad’ called the Civil Cooperation Bureau (CCB), and, in Lubowski’s case, specifically to individuals within this CCB who had been former policemen in South Africa. However, the former policemen who were named in the case (Chappies Maree, Staal Burger, Calla Botha, Slang van Zyl, among others) had no record of ever having carried out, or organized, professional murders. Their records consisted of harassment, beatings, torture and other ‘dirty tricks’.

Skills of a certain kind

Dulcie September, Anton Lubowski and Chris Hani (and also David Webster, the academic who had -according to Mail & Guardian’s predecessor, the Weekly Mail – stumbled on South African military intelligence smuggling operations near the Kruger Park, and whose murder in 1989 was similarly attributed to ‘the CCB’) were cornered in a spot without witnesses, shot in the head, and died immediately. Carrying out such a murder needs skill and experience of a kind that an average South African policeman simply did not possess.

Former military Special Forces operative Guy Bawden confirmed in an interview in the late nineties that he and his fellow soldiers did not think highly of ‘the CCB’. “We were laughing at these CCB policemen. They were parading around, sweating and in wigs, in the heat in the frontline states. We knew that they were just a label. For when an operation needed to be denied.” South African Special Forces operatives were often mercenaries, and they were indeed used, sometimes privately, for operations that needed to be denied. Irish mercenary Donald Acheson, of Special Forces army battalion Recce 3, was identified in a Namibian inquest as Lubowski’s real assassin.

He disappeared in 1991 and is now thought dead. An army buddy of Acheson’s (name known to ZAM) has told a confidante that he was also involved in the Lubowski murder and that the order came from a South African government minister who felt that Lubowski was ‘messing with his business’.

Like the Afrikaans policemen in ‘the CCB’, the man officially identified as the murderer of Chris Hani, Janusz Walus, was also no professional hit man. Witnesses who identified a second man on the scene of the crime, a man with actual secret service and gun runners links, probably had something to say worth listening to. “But police came at night to scare the children, mess up my place and tell me that I should stay away from trying to testify”, recounts a witness who saw the second murderer. “I gave up after that”.

The Chris Hani murder docket shows to which extent the murder investigation was manipulated to result in the sole convictions of Walus and Derby-Lewis. Not only did the investigating officers ignore witnesses like the neighbour quoted above, they also refrained from interrogating Janusz Walus’ employer, chemical trucker Peter Jackson. The Security Police (“who were in charge of the investigation,” according to Brixton Murder & Robbery Squad’s chief inspector Michael Holmes), told Holmes’ men not to bother exploring the man or his arms trade and secret service contacts. This, even though a list of these contacts (including an Armscor man called Colin Stier) is also neatly contained in the docket. “Jackson is cooperating fully and does not need to be questioned,” the instruction to the police officers says. Another police instruction, on the authority of Security police Captain J.H. de Waal, states that “information about Peter Jackson will not be followed up”.

Walus’ diary, prominently listing several reminders to ‘Phone Peter’ in the run-up up the murder, has disappeared from the docket altogether, though a copy of it (missing the page of the week of the murder itself) is still there.

NIA assistance

What also casts doubt on the police findings is the fact that the murder scene in the Hani case was, within seconds of the shooting, professionally shielded by a self-confessed operative of the National Intelligence Agency. Michael Buchanan, who happened to live right opposite Chris Hani, was first to arrive in the yard where he lay shot. (In the world of secret services, it is customary that a technically trained operator ‘sweeps’ the murder scene, to prepare it for the police only to find what they’re supposed to.) Buchanan, in a telephone conversation with me, and later in a faxed written statement, did not go into his actual role at the scene, but stated clearly that he worked for the “new intelligence service” and that he had “helped avert civil war.” (It was also Buchanan who threatened violence and “Gerrie Nel and the Scorpions” against both Jacana and myself.)

Chief Inspector Michael Holmes of the Brixton Murder and Robbery Squad was, throughout, (weirdly) happy with the ‘assistance’ his team had received from the Security Police. “We didn’t need to look at all the evidence,” he told me, “because the Security Police put everything we needed in a box for us to work with.” An important part of that evidence was the ‘right-wing gun’ that was used in the murder, that originated from violent right-wing extremist Piet ‘Skiet’ Rudolph’s armory. The gun had been procured by Clive Derby-Lewis upon Janusz Walus’ insistence. “Clive was asked repeatedly by Walus to get him a gun and that’s what he did” Inspector Holmes told me.

There is no indication that Derby-Lewis ever did anything else and actually, by procuring a ‘right-wing gun’, Derby-Lewis worked to cement the cover story of a plot of a few right-wing individuals, rather than to assist with the actual murder. Walus didn’t need a gun: according to the case docket, he already owned four guns at the time. His, Walus’, successful insistence on getting a right-wing gun, went a long way to paint the hapless right-wing fanatic Derby-Lewis as the ‘mastermind’ of the Hani murder. (Ironically, Clive Derby-Lewis may well be under the impression that he was, in fact, a mastermind. He did get the gun, after all.)

A big debt

The one who knows, if not the whole truth, at least more of it, is without doubt Janusz Walus. So why doesn’t he talk? Perhaps because he knows that it wouldn’t help him – after all, he was still part of the murder plot and it would be unlikely that he would be freed? Or because he has a sister, other relatives and friends in South Africa, among whom a brother who maintains excellent relations with the SA military? Or is it the debt that his family, according to Peter Jackson, still owes to Walus’s former boss? Jackson had ‘helped’ the Polish immigrants during the apartheid years to set up and run a glass cutting factory in the Qua Qua bantustan. “The Walus family incurred a big debt to me in the process,” Jackson told me, on the one occasion when I managed to pin him down. “Walus was paying it off to me on their behalf.”

Maybe it is only Janusz Walus who could still rescue this story from falling into a big silence again.

https://www.zammagazine.com/chronicle/chronicle-11/202-essay-chris-hani-murder-revisited