Johann Rupert, Executive Chairman of Remgro and CEO of Richemont, said recently in London at a shareholders meeting that “radical economic transformation” was just a codeword for theft.

The ANC responded within hours with a blistering statement and a torrent of comments, straight from the socialist-Marxist economic textbook. They warned Rupert to remain silent because he is a “beneficiary of apartheid’s exclusionary policies” with “ill-begotten privilege”. The insinuation is that he opposes economic empowerment and change, and that he does not act in the interests of a democratic system.

Even though no comments have been forthcoming from other South African business leaders, it can be assumed that a substantial number of them agree with him on this point and say exactly the same in private conversations and in board meetings.

Johann Rupert, as most people know, is a prominent personality in his own right and does not need anyone to defend him. But his statement and the ANC’s reaction speak to more than Rupert the individual and the ANC as an organisation.

Rupert and his father Anton before him have been longstanding supporters of the Small Business Corporation (now known as Business Partners). He was a founder member (with a number of others) of the R1 billion Business Trust, formed as a partnership with Government in the late 90s, and served on that Trust with cabinet ministers. He is a staunch supporter of South Africa internationally and often canvasses for more investment into the South African economy.

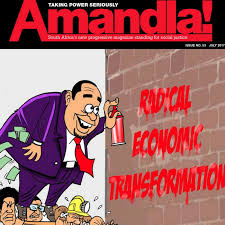

His statement must first and foremost be seen as frustration with and a condemnation of the Zupta clique, who are driving the country towards bankruptcy, with the support of the Bell Pottinger-formulated theories of “white monopoly capital” and “radical economic transformation”. In doing so, he is on the same page as various leaders in the ANC and government. Cyril Ramaphosa does not use the term “radical economic transformation”, but rather speaks of “inclusive economic growth”. Former Finance Minister, Pravin Gordhan, and former Deputy Minister of Finance Mcebisi Jonas, are openly suspicious of “radical economic transformation” and its association with state capture and have estimated the losses to the country at more than R100 billion.

It is common cause that the ANC as an organisation is in chaos. Its leader has been embroiled in numerous court cases and has 783 counts of fraud hanging over his head. He, his family and many of his appointees and supporters are implicated almost daily in the flow of leaked Gupta emails, sometimes criminally. There are no less than six candidates as successor to President Zuma. In four of the provinces, internal lawsuits between factions of the ANC are under way. There is disunity between the ANC and its former alliance partners, COSATU and the SACP. There are actually at least two ANC’s: the Zuma ANC and the constitutionalists (for lack of another description).

It is the Zuma-ANC’s official spokesperson who criticised a senior business leader in a strongly-worded official statement. Given the above-mentioned picture of the party, it can only be interpreted as a desperate attempt to offer a show of unity to outsiders. It is almost as if to say we stand together (at least on this issue); do not dare criticise us.

A number of points spring to mind: the first is that is not possible or useful to generalise about the prosperity of white South Africans and benefits gained through apartheid. Of course there were business people who derived economic benefits from apartheid, directly and indirectly. However, the nature and intensity of the benefits differ fundamentally on a case-by-case basis. In this case, Rupert’s father started what is today Richemont in a garage in 1940, with ten pounds as capital. Surely, our debates must be more nuanced than “ill-begotten privilege”?

Secondly, the Constitution affords all South the right to have their say on issues affecting the country. It’s a fairly recent phenomenon that only certain people may raise political views and offer criticism. This goes against the constitutional right to freedom of speech – and makes a mockery of democracy.

Thirdly, the Zuma-ANC must not subvert the truth in an attempt to offer a show of unity to the world. Some of its own leaders say (although in somewhat different terms) exactly what Rupert dared to say. It behooves the ANC as a party rather to examine on what values it grounds its policy and builds unity.

Fourthly, there are also people who dismiss Rupert’s comments as “irresponsible” in the current tense political climate. The implication is that the ANC alone should discuss their and the country’s future, and that advantaged white people should rather sit in the corner and keep quiet. But what is forgotten is that the confidence of the business sector is as low as it was in 1987 when PW Botha pushed the country closer and closer to the abyss. Most business people (including Rupert) realise this and are extremely worried. That’s why they are holding on to millions in cash and not investing in new ventures. There is a wait-and-see attitude that has now already lasted almost two years. This is a direct consequence of Zuma’s lack of leadership, his ties to the Guptas and slogans such as radical economic transformation and white monopoly capital.

It is therefore in the national interest (and their own interest) that business leaders should raise their concern about what is happening in South Africa. Business Leadership SA has made some strong statements in this regard. But more is needed. As in PW Botha’s last days, we must realise that the hour is late. The silence must be continuously broken.

By Theuns Eloff: Executive Director, FW de Klerk Foundation

21 September 2017

http://www.fwdeklerk.org/index.php/en/latest/news/700-article-business-radical-economic-transformation-and-the-anc-the-hour-is-late