RICHARD DOWDEN Sunday 17 April 1994 23:02 BST

IN THE days leading up to the South African election we will be told by journalists and commentators that democracy has finally arrived in South Africa and that black South Africans will be voting for the first time. Neither statement is quite true.

Democracy has a long, if contorted, history in South Africa. For nearly 100 years there was a non-racial franchise and the electoral role did not become exclusively white until 1956. The Coloured Vote Bill in that year was the final blow to a non-racial democracy which had been whittled away over the decades. Like many apartheid laws passed by the National Party government in the Fifties, it was not a radical departure from the past. The legislation which created apartheid was based on existing laws and in many cases simply tightened or tidied them.

The myth that there has never been democracy in South Africa is linked to a second myth. Most people think they know that apartheid was an invention of the Afrikaners and their belief that South Africa should be ruled exclusively by whites. Conversely, it is usually thought that the English tradition in South Africa was non-racial and democratic. In fact, the British tradition, as purveyed by both English-speaking South Africans and the parliament at Westminster, has played a less than glorious role in establishing democracy.

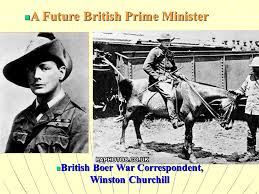

It was two renowned Englishmen, Cecil Rhodes and Winston Churchill, who at crucial moments planted the seeds that were to ripen into policies which deprived black people of democratic rights in South Africa. A third, Jan Smuts – an Afrikaner by birth who became a committed supporter of the British Empire – was also an architect of laws which were later to become the framework of apartheid. Like Churchill, Smuts has a statue in Parliament Square, but in South Africa both will go down as men who destroyed rather than built democracy in the country.

Let’s take Rhodes first, the Bishop’s Stortford boy who wanted to build an African empire from Cairo to the Cape, who invented Rhodesia and left us with the De Beers diamond monopoly and 160 Rhodes scholarships at Oxford. A millionaire from diamonds and gold before the age of 30, Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape in 1890. For more than 40 years the Cape had had a non-racial franchise which allowed anyone, irrespective of race, with property worth pounds 25 or wages of pounds 50 a year to vote for representatives in an Assembly which made laws for the colony.

Rhodes believed that the world should be ruled by the Anglo Saxon and Teutonic races: one of his dreams was to force the United States of America back into the British Empire. Although Africans represented a minority of voters and did not vote as a block, Rhodes passed two laws simultaneously which caused large numbers of them to be struck off the electoral role. One, the Glen Grey Act, limited the amount of land Africans could hold; the other tripled the property qualification for the vote. Many Africans now had insufficient property to qualify and would find it almost impossible to get back on the list because of the legal limit on the amount of land they could hold.

The next blow to democracy came after the Boer war. Elsewhere in the world the imperial government in London exercised a veto over its colonialists to protect the interests of the native people of the colony from the settlers. In Kenya, for example, London blocked several attempts by colonists to make Kenya a ‘white man’s country’. Ultimately, in Rhodesia, Britain imposed sanctions to reverse Ian Smith’s Declaration of Independence. In South Africa, however, the veto was abandoned when the Union of South Africa Act was passed in 1910 and the man who played a vital role in its abandonment was Churchill.

If you read the debates that led up to the Act of Union, the most striking thing is that the words ‘racial conflict’ referred to the Anglo- Boer war. What we would call the racial issue was then ‘the native problem’. The British had fought the war partly, it was said, to protect the interests of the natives from the Boers, the Afrikaners.

During the war the British had encouraged Africans to work for British victory, which they did in large numbers. With victory, Britain might have been expected to extend the Cape non-racial franchise to the conquered territories of the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony so that blacks would be represented in the whole territory the way they had been in the British colony. But not only did they not do so, they also limited the ‘native’ vote to the Cape. Africans were to have no say in the election of a national parliament, although they retained their voting rights to the Cape parliament.

The young Churchill, then Under-Secretary for the Colonies, had covered the South African war as a journalist and had been captured by – and escaped from – the Boers. His knowledge and influence in making the agreement after peace was signed was crucial. In a debate in July 1906 he called the peace treaty ‘the first real step taken to withdraw South African affairs from the arena of British party politics’. He argued passionately that the Afrikaners should be allowed self-rule, a self-rule which he admitted would mean that black Africans would be excluded from the vote.

In parliament he told those who pointed out that the treaty had enshrined the rights of Africans that the Afrikaners interpreted the peace treaty differently. He said: ‘We must be bound by the interpretation which the other party places on it and it is undoubted that the Boers would regard it as a breach of that treaty if the franchise were in the first instance extended to any persons who are not white.’

When South Africa was discussed four years later, Churchill’s successor tried to reassure parliament that the Afrikaners would come round to the view that it was wiser to include Africans in the franchise. A delegations of Africans from the South African Native Congress, the forerunner of the ANC, came to lobby parliament at Westminster, but to no avail.

Because of Churchill and his policy the British parliament had already washed its hands of responsibility for the rights of its black citizens in South Africa. When the new parliament in South Africa passed the Land Act, making it illegal for Africans to purchase land from Europeans anywhere outside the reserves, a delegation of Africans who came to London to protest were told that it was a matter for the South African parliament.

The deputy leader of the party which passed the Land Act was Jan Smuts. He had fought against the British and his troops had been responsible for massacres of unarmed Africans acting as drivers and porters for the British army. After the war he played a crucial role in striking the deal between Britain and the Afrikaners and is usually regarded as the man who represented liberal democratic values in South Africa. In fact, Smuts believed that South Africa should be a ‘white man’s country’ and he believed in ‘segregation’ – which is simply English for apartheid.

He passed the first piece of legislation which separated white and black areas and in 1920 the Native (Urban Areas) Act which laid down the principle of residential segregation in urban areas, keeping blacks away from white residential areas. He also initiated the principle of reserving jobs for whites in the Mines and Work Act. In the 1929 ‘Black Peril’ election, when fear of being dominated by Africans became the major issue, Smuts demanded that the rate of black integration into white society must be curtailed. He also called for South African influence to be extended north and east in the creation of a British Confederation of African States.

Smuts lost that election to J B Hertzog’s National Party, but five years later they formed a coalition and democracy took another blow. The Native Representation Act of 1936 took away the franchise from Africans in the Cape. Instead, Africans in the whole country were to be able to elect four white men to represent them on a council, with eight other appointed members. Although ‘coloureds’ remained on the Cape electoral role until 1956, the 1936 act was the final stage in a long retreat from democracy in South Africa.

When the National Party won the 1948 election on the platform of apartheid, it did not have radically to rewrite South Africa’s laws. The foundations of apartheid were already in place. Sex outside marriage between races was already banned, but it was carried to its logical conclusion in the 1949 Mixed Marriages Act and the Immorality Act of the following year which banned any sex between races.

The Native Laws Amendment Act, built on Smuts’ Native (Urban Areas) Act, redefined which Africans were allowed into urban areas. The laws affecting the various pass laws that were already in existence were amalgamated into the Abolition of Passes and Consolidation of Documents Act and forced all Africans to carry a single pass. It was made a criminal offence not to produce the pass book when required by the police.

Various laws relating to urban affairs which prescribed segregation were gathered into the Group Areas Act which made separation absolute and gave the government powers to define an area as White, Black, Indian or Coloured. The Industrial Conciliation Act built on the foundations of Smuts’ Mines and Work Act to restrict further black rights at work. On the crucial issue of land, the Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act gave the government power to move African tenants from privately or publicly owned land and tidy up the land into segregated areas. This was the completion of legislation which began with Cecil Rhodes’ Glen Grey Act, nearly 50 years before.

The arrival – or rather rearrival – of non-racial democracy in South Africa is clearly cause for celebration, but it should not be an occasion for British self-satisfaction that Western-style democracy and the Mother of Parliaments have won another convert. Perhaps, though, there should be half a cheer for Churchill’s colleague, Lord Elgin, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who in 1906 expressed the fervent wish that the Afrikaners would, ‘in some time to come’, see the good sense of granting ‘reasonable representation to the natives’. I suppose you could say his wish has come true – at last.

Richard Dowden is in South Africa to cover next week’s election.

(Photographs omitted)

https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/apartheid-made-in-britain-richard-dowden-explains-how-churchill-rhodes-and-smuts-caused-black-south-1370856.html