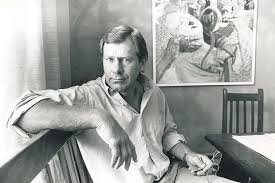

Michael Savage

Emeritus Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Correspondence to

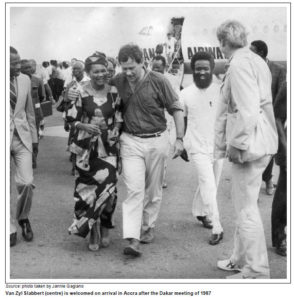

Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, known to his friends as Van, was born in Pietersburg (now Polokwane) on 02 March 1940 and died in Johannesburg on 14 May 2010, aged 70. After initially following an academic career, he was, against all odds, elected Progressive Party Member of Parliament for Rondebosch in 1974. He became the official Leader of the Opposition in 1979, before suddenly leaving parliament in 1986, to become co-founder of the Institute for a Democratic Alternative in South Africa. In the following year, 1987, he was a key person in helping arrange the meeting of 61 people from within South Africa with the exiled ANC in Dakar, Senegal. This meeting caused considerable controversy in South Africa, but many historians assess it to have contributed significantly to the later negotiation process undertaken in the lead up to the 1994 democratic election. In subsequent years, Slabbert became involved in the business world, serving on the boards of several large companies, as well as being active in civil society.

Slabbert and his twin sister, Marcia, did not have an easy start to life; a broken family and an alcoholic mother led to them being removed from home at age 7, to be brought up by other relatives. Despite this, they both shone at school, with Slabbert becoming head boy of Pietersburg High School.

In 1959, Slabbert enrolled at the University of the Witwatersrand to study Latin and Greek. The following year he moved to the University of Stellenbosch, in order to register at the Dutch Reformed Church’s theological seminary, but, 18 months later, he left it to concentrate on sociology. He graduated with a BA in 1961 and, after completing Honours and Master’s degrees in sociology, graduated with a PhD in 1967, with a thesis that focused on the functionalist theories of Harvard’s Talcott Parsons. From 1967 to 1971 he held academic posts at the Universities of Stellenbosch, Rhodes and Cape Town, before becoming Professor of Sociology at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1972.

Slabbert never lost his love for academic research, discussion and debate and maintained close contact with a wide range of prominent academics, both in South Africa and elsewhere, throughout the course of his adult life. For him, there was no sharp dividing line between academia and public life, as was reflected in his publications, his public speeches and in the ways he applied his mind to analysing what he considered to be South Africa’s key challenge – realising a well-functioning democratic state. ‘My passion is researching transition for authoritarian regimes to democratic outcomes and South Africa absorbs my attention’, he wrote in an uncirculated and abbreviated curriculum vitae in 1991. On entering public life, he brought a scholarly approach to his analyses of issues, which, as a gifted communicator, he was able to easily convey. This approach, coupled with his charisma and his abhorrence of racism, attracted many people to follow his example and become involved in politics and public life.

Slabbert published four books: The last white parliament (1985), The system and the struggle (1990), Tough choices (1999) and The other side of history (2006); and was the co-author of a further two: South Africa’s options (1979), with David Welsh, and Comrades in business (1997), with Heribert Adam and Kogila Moodley. He was a Visiting Scholar at MIT in 1984, the Tanner Lecturer at Brasenose College in 1984 and a Visiting Research Fellow at All Soul’s College (both at Oxford University) in 1989-1990. To his enormous pleasure in 2008, he was appointed Chancellor of the University of Stellenbosch, a post he sadly had to relinquish the following year due to ill-health.

But it was in national public life that Slabbert made his greatest contributions. He was wholly unafraid of stating unpopular views and taking controversial positions. His abrupt departure from Parliament, declaring that it ‘had almost no relevance at all’ drew considerable criticism, but also praise from many of the disenfranchised and, thereafter, he belonged to no other political party. These two factors, alone, essentially resulted in his absence from the 1993-1994 multiparty negotiation process that established the format for the first democratic election and provided the initial draft of the constitution for the emergent democracy. His already established and considerable negotiation skills, together with his knowledge about transitions to democracy in other countries, meant that his absence left the negotiation process all the poorer.

After leaving Parliament, Slabbert’s contributions to public life took varied and important forms. He co-chaired the difficult negotiations over the period 1991-1994 that led to Johannesburg becoming a unified metro with a coordinated local government. In 2002, he was appointed chair of a commission examining electoral reform. Its carefully constructed report recommending a mixed proportional representation and constituency-based voting system (akin to the existing German one), was quietly shelved by the then President Mbeki’s cabinet. As a result, many people near to Slabbert puzzled over why the close relationship he had established with Thabo Mbeki, initiated before Slabbert had left Parliament and the growth of which was manifest in their warm interactions at the Dakar talks with the ANC, had seemingly come to naught on Mbeki’s return from exile.

In searching for money to hold the Dakar meeting with the exiled ANC, Slabbert had established a relationship of mutual trust with the American financier, George Soros, who shared his appreciation of the writings of Karl Popper. In 1993, Soros established the Open Society Foundation for South Africa, which Slabbert chaired along with the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, a later initiative created as part of the Soros foundation network.

Slabbert was a multitalented man with compassion and incisiveness, a love for the Afrikaans language, a large sense of humour and a low-tolerance threshold for indecisive discussion at meetings. But, above all, he had a deep commitment to South Africa and to building democracy in this country. He leaves behind his wife, Jane, his children, Tania and Riko, five grandchildren, and a gap in public life that sorely needs filling.

http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0038-23532010000300009