Speech by Flip Buys, Chairperson of the Solidarity Movement at the summit held by the FW de Klerk Foundation on the future of multiculturalism in South Africa, 2 February 2016

The future of multiculturalism in South Africa 2 February 2016

Introduction

US Nobel Prize economist Milton Friedman said a policy should not be measured by its intentions but by its outcomes. For this reason, this summit is very timely as it has become necessary to reflect on the multicultural outcomes of the constitutional dispensation to prevent us from ending up in an irreversible slide towards monoculturalism.

The importance of multiculturalism

Political thinker Andrew Heywood expressed the view of a growing number of political scientists that multiculturalism may become the ideology of the 21st century,i the reason being that countries and communities are becoming increasingly multicultural as a result of migration and global mobility. Heywood thus argues that the main political issue present and future generations are facing is the quest to find ways in which people from different cultural and religious traditions can live together in peace.

This reality has forced a growing number of Western states, including almost all the member states of the European Union, to officially adopt multiculturalism and to incorporate it in public policy.ii The question is how the growing cultural diversity in most countries can be reconciled with national unity. The answer is to be found in “unity in diversity” as key theme of multiculturalism and the foundation of the South African Constitution.

Multiculturalism presupposes a positive acceptance of diversity based on the right to recognition of and respect for different cultural groups. The resulting policy is characterised by the formal recognition of the particular needs of specific groups and a desire to ensure equal opportunities for all. The aim is not to merely “tolerate” cultural communities but to actively promote their interests.

A simple majority democracy is too simplistic to regulate the complexities of a multicultural society. In monocultural systems the individual rights and freedoms of majorities automatically prevail over the individual rights of minorities. In such systems, minorities will always have to fight for that which majorities accept as a given, for example to decide on the language policy of their nearest school.

However, a monocultural system also easily leads to conflict because political competition degenerates into competition between communities on the grounds of identity, instead of being between individuals on the grounds of policy. According to US political scientist Timothy Siskiii, the fact that minority communities enjoy political franchise but not sufficient voting power causes them to experience democracy not as a freedom but as domination, given that minorities cannot easily safeguard their fundamental interests democratically against political majorities.

A multicultural system, in contrast, leads to minorities participating in the fundamental issues that affect them, ensuring that public policy reflects the interests of all people and groups and not only those of the dominant groups. In this way, multiculturalism can be regarded as a determinant condition for the equal enjoyment of the individual rights of citizens. Put differently, it ensures equal citizenship as Judge Sachsiv had put it:

Equality means equal concern and respect across difference. It does not presuppose the elimination or suppression of difference. Respect for human rights requires the affirmation of self, not the denial of self. Equality therefore does not imply a levelling or homogenisation of behaviour or extolling one form as supreme, and another as inferior, but an acknowledgment and acceptance of difference. At the very least, it affirms that difference should not be the basis for exclusion, marginalisation and stigma. At best, it celebrates the vitality that difference brings to any society.

It brings political arrangements in line with multicultural realities; protects minorities from forced incorporation into the majority; prevents the alienation, isolation, lack of power and political impotence of cultural minorities; it guarantees their full participation in public life; and it ensures their loyalty to the country and the nation because their fundamental interests are being protected. In this way, unity and diversity are not opposite poles as they are based on multiple identities that are equal. All are South African citizens with full individual rights, at the same time all enjoying “cultural citizenship” of a particular cultural community.

Such “politics of recognition,” as the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylorv refers to it, prevents the democratic exclusion of cultural minorities simply by virtue of their numbers. Recognition of cultural communities safeguards individual rights; distributes decision-making power more evenly; and prevents its monopolisation in the hands of a certain elite group, consisting of the majority, which only articulates and promotes the interests of the majority. Such recognition protects a group’s way of life and limits the negative consequences of unequal political power. This ensures group access to government, deepens democracy and ensures democratic accountability and responsiveness.

Cultural liberty as model for multiculturalism

The UN’s influential Human Development Report 2004,vi titled “Cultural liberty in today’s diverse world,” expounds in detail a workable model for multicultural societies. The report describes cultural liberty as the freedom people have to choose their own identity and to pursue it without prejudice.

Johannesburg political scientist, Professor Deon Geldenhuys, says that cultural rights, together with political, civil, economic and social rights, have globally become inextricably part of the family of human rights.vii The UN report also states that in the modern world of increasing democratisation and global networks, policies that inhibit cultural liberties have become less and less acceptable.

The report strongly recommends cultural liberty in multicultural countries, setting it as a vital precondition for peaceful coexistence and national unity. It cautions against attempts to create, through nation-building, culturally homogeneous states with a single identity. The latter is regarded as a power political strategy that is irreconcilable with a democratic political culture. Instruments of power, such as the centralisation of political power, refusing minority groups to enjoy local autonomy, to pursue one official language and to follow an education system that gives precedence to the language, history and symbols of one group over that of other groups, are strongly denounced.

The report describes the violation of cultural liberty as an act that does not recognise or respect the values, institutions and way of life of a cultural group, criticising it as “cultural exclusion”. It distinguishes between two forms of cultural exclusion, namely exclusion based on way of life and exclusion of participation.

Exclusion based on way of life takes place when a particular group’s preferred way of life is not recognised with the insistence that all follow the same way of life. It could take the form of restrictions on a group wishing to practise its language, culture or religion, such as the prejudicing of a group’s language by introducing another language as the only language in the civil service and education. The vandalising of a cultural group’s statues is another good example.

The second type of prejudice pertains to participation exclusion in terms of which there is discrimination insofar as political, economic or social opportunities are concerned, for example exclusion when it comes to employment, business, education and politics. The report emphasises that ensuring cultural liberty and preventing cultural exclusion ask for more than the provision of civil and political freedom by means of majority democracy. What are called for are multicultural policies which have as point of departure that States should acknowledge cultural differences and needs in their constitutions, legislation, policies and institutions.

Without cultural liberty democracy will, in practice, degenerate into freedom only for the majority.

The 1994 constitutional settlement

In a defining sense, the exchange of majority government for minority protection and human rights constituted the essence of the 1994 settlement. This was achieved by means of providing for the multicultural reality through the inclusion of comprehensive constitutional protection for language and cultural communities.

One of the underlying assumptions was that language and cultural communities should have spaces where they could be a majority to prevent every aspect of their existence being dominated by demographic majorities. Thus political, cultural and even economic marginalisation could be prevented and all could have citizenship of equal value.

The Constitution provides for 11 official languages; mother-language instruction (including the provision for single medium institutions and universities, for example); institutions for persons belonging to language, cultural and religious communities; the values of freedom, human dignity and equality enshrined in the Bill of Rights; a ban on unfair discrimination; the creation of a general council to protect the rights of persons belonging to language, cultural and religious groups; the establishment of councils for such communities and special constitutional institutions, such as Pansat, to watch over democracy (and multiculturalism). Section 235 of the Constitution even recognises the right to pursue various forms of self- determination.

The authors of the Constitution most likely heeded the warnings of statesmen such as Henry Kissinger and multicultural society experts such as Donald Horowitz about the challenges such countries pose for democracy.

Very significantly, Kissinger declared: “It is particularly important to understand the obstacles to democracy in a multi-ethnic and multi-religious society. In the West, democracy evolved in homogeneous societies. There was no institutional impediment to the minority’s becoming a majority. Electoral defeat was considered a temporary setback that could be reversed [in the West]. But in societies with distinct ethnic or political divisions, minority status often means permanent discrimination and the constant risk of political extinction.”viii

Donald Horowitz, author of the authoritative work, Ethnic groups in Conflict ix, offered the following advice: “For these societies, special sets of institutions seem to be required to insure that minorities who might be excluded by majoritarian systems be included in the decision-making process, and that inter-ethnic compromise and accommodation be fostered rather than impeded”.

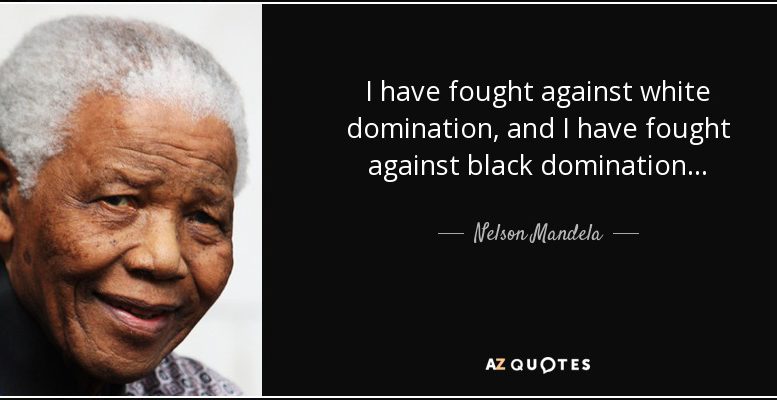

The alternative, Horowitz cautioned, was that white minority rule would simply be replaced by black majority rule.

Constitutional theory versus political practice

South Africa is a multicultural country, and to make it work, we obviously have to have a multicultural dispensation. The very theme of this conference hosted by the De Klerk Foundation, however, is an indication that there is serious concern about the future of multiculturalism. My interpretation is that there is a growing feeling that our increasingly monocultural state is aiming at shaping the multicultural reality of the country according to the government’s monocultural policy.

Probably, the reason for this is that our multicultural reality clashes with government’s political ideology of a monocultural nation. Instead of working with realities and viewing culture communities as the constituent building blocks of the nation, the state is trying to transform the realities according to a political ideology. The strategy to achieve this is to attenuate nation-building and reconciliation to incorporation into the majority. This is pursued by trying to transform the country and all its institutions into demographic mirror images of the population composition by means of the state ideology of transformation. In this way, peculiarly enough, under the banner of promotion of diversity, the opposite, namely similarity, is enforced.

In this process, the ANC is achieving its aim of “African hegemony”, linked to ANC control through their policy of cadre deployment. This is the essence of the decisions of the ANC’s 1997 Mafikeng Conferencexwhere the policy of transformation was accepted, a term which does not even appear in the Constitution. Where transformation initially was embraced as a process to move away from apartheid, it gradually became clear that the ultimate aim is directed at replacing the then white domination by black African domination.

South Africa is now becoming a “transformation state instead of a constitutional state”, where the Constitution is interpreted within the framework of political transformation instead of the political policy of transformation being interpreted within the framework of the Constitution. While the wording of the Constitution has remained essentially the same in spite of several amendments, in practice, government is moving ever further away from many of the most important constitutional provisions.

The most important examples of this are the constitutional provision for multilingualism which, in practice, has become English monolingualism; equality which has become representivity, property rights which are being diluted; the introduction of a welfare system under the banner of socio-economic rights; the co-opting or disempowerment of certain constitutional institutions by government; and institutions for language and culture groups such as the Commission for the Promotion and

Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities, where in practice nothing worth mentioning has happened.xi

In short, the ANC is using its overwhelming political power to undermine the multicultural reality of the country and the constitutional provision for this, with a monocultural political ideology. It is now nearing a point where the ANC’s opposition to “Eurocentrism” has turned into the active promotion of Afrocentrism.

Among Afrikaners, a broad view is gaining ground that the ANC made concessions during the constitutional negotiations to acquire power, but now they are using this power to achieve their original objectives. This is the reason for a growing disillusionment with the ultimate result of the political changes for which most Afrikaners voted enthusiastically in the early nineties. They thought it was essential for black people to get full rights, but now they are concerned that the revolution has been going beyond equal rights and that their own rights are now being prejudiced.

They wanted a fully-fledged democracy, but without their own democratic rights being dominated. They thought it only fair that black people should get full civil rights and equal opportunities, but they did not want to feel like second-class citizens themselves. They voted for the abolition of racial discrimination, but they did not expect to become the target of such discrimination themselves.

They thought it was only fair if the indigenous languages could achieve their full potential, but they thought it could be done without Afrikaans being marginalised. They agreed that black people should be empowered economically, but now they are worried that the enrichment of the elite under the banner of black empowerment is harming the country and could result in the disempowerment of many.

They wanted the ANC exiles to return from abroad, but they did not want circumstances to change to such an extent that their own loved ones would have to leave the country. They were of the opinion that Afrikaner control of state media could not be justified, but they did not want this to be replaced by ANC control.

They believed that black people should get their fair share of taxpayers’ money without relinquishing their own fair share. They accepted that “black” history had to get its fair place under the sun, but they did not want to see Afrikaner history being criminalised. They understood the ANC’s point of view that their place names and heritage should gain more recognition, but they did not want to see their own historic names and heritage being marginalised without ado.

They appreciated the need for an improvement of black education, but now they feel that the ANC is taking control of and anglicising Afrikaans education and institutions.

Initially, Afrikaners supported affirmative action, but they reject it being abused to anglicise institutions and to bring them under ANC control through the ideology of representivity. Afrikaner voters exchanged minority control for a democratic constitutional state, but they are becoming most concerned that the country is beginning to change into a transformation state. In short, many Afrikaners feel that they voted for democracy but ended up with a negotiated revolution.

There are no convincing signs that the ANC views the future as multicultural, but they are using political power to block constitutional spaces for multiculturalism and are forcing monoculturalism onto the country. I even want to go as far as to say that in the ANC’s vision for the future there is no place for Afrikaners as a culture community. Rather, they are striving for a dispensation where Afrikaans individuals are incorporated into the majority by abandoning their insistence on their constitutional rights as a culture community.

The fact that there are still single-medium Afrikaans schools and that in some places space still remains for Afrikaans at university level is notwithstanding rather than owing to the ANC. Civil society has to defend its obvious constitutional rights and democratic space on a daily basis, and it is ironic that protecting these rights nowadays is sometimes viewed as “rightist”.

The ANC’s view of democracy apparently is that even if only 51% of voters support them, they still have to have 100% of the power. They are clinging doggedly to obsolete notions such as “balance of power”, instead of granting everybody a place under a multicultural sun in a spirit of “balance of interests”. In this way, the gulf between constitutional and political spaces is becoming ever wider.

Consequences of the slide towards monoculturalism

The slide towards monoculturalism has already caused the Afrikaner’s constitutional rights and fundamental interests drastic and irreparable damage.

I find it tragic that South Africa did not opt for a formal federal dispensation at the time of major transition. The two main advantages of federalism are that it entrenches multiculturalism more efficiently and that it limits the power of a centralist party. As Lord Acton said: “Of all checks on democracy, federation has been the most effective and the most congenial … The federal system limits and restrains the sovereign power by dividing it and by assigning to Government only certain defined rights. It is the only method of curbing not only the majority but the power of the whole people.” It is actually the only real check and balance there is: power must be balanced by counter-power – not as is the case in the current system where power is balanced by own power.

A federal dispensation entrenches multiculturalism precisely because cultural communities are officially recognised and do not only have entrenched rights but also constitutionally entrenched powers to exercise them. The Achilles heel of multiculturalism in South Africa is the fact that the majority may decide how minorities may exercise their rights. This leans towards a system where we not only have a lack of minority rights, but one that also entrenches majority rights in the name of democracy.

The starting point of a democratic multicultural strategy should therefore be the protection of its constitutional spaces and the expansion of its political spaces. Cultural freedom for cultural communities is not only a right but a prerequisite for survival. A multicultural system gives cultural communities a say and the original decision-making powers regarding their fundamental interests, instead of having to place all of it in the middle of the political arena where the majority decides on it. This is not democracy but domination.

It would, however, not be fair to blame only the government for this. Karl Marx said that the ideas of the ruling class become the ruling ideas of society and this corresponds with the ANC’s pursuit of a “hegemony of ideas”. To a large extent, the party has succeeded in having its state ideology of transformation accepted as the “ruling idea” of society. This resulted in a political ideology rather than the Constitution becoming the “national norm” of the country, and this is being pursued as the obvious benchmark for everything in the country by business people, university councils, the civil service, journalists, academics, and increasingly by the general public.

The elevation of the ruling party’s policy to the country’s ruling ideology has even persuaded the councils of almost all the historically Afrikaans universities to pursue it as par for the course. To a large extent a mainly depoliticised Afrikaans elite no longer has the intellectual tools and the political and cultural self-confidence to protect the constitutional spaces for multiculturalism. Thus the gap between constitutional theory and political practice widens. The result is that political power eventually becomes stronger than constitutional authority, to the detriment of the fundamental interests of cultural communities as well as the institutional autonomy and academic freedom of these institutions. Perhaps the root cause of all this is the naïve assumption that constitutional provision makes political action unnecessary.

Recommendations for the promotion of constitutional multiculturalism

Central role of civil society

It is clear that civil society will have to take responsibility for promoting constitutional multiculturalism as the government’s stance in this regard is not merely neutral; government is actively promoting monoculturalism.

The DA’s growth strategy requires that the party should reposition itself as a party for the demographic majority in South Africa, and the party does not have the appetite to make multiculturalism a significant part of its political platform. This is unfortunate, since liberal parties, as parties standing for freedom, should provide space to accommodate the freedom of other cultural communities as well.

Sociologist Lawrence Schlemmer emphasised the role of civil society by stating that “Minority groups in South Africa would therefore be well advised to develop strategies for political participation which do not assume electoral growth and leverage. Mobilisation for a more effective voice in civil society and in the lobbying process seems to be the obvious strategy to follow”.

Philosopher Ernest Gellner considered a network of non-governmental organisations to be the best way to balance the power of a ruling powerful monopoly. Organised language and cultural communities promoting their rights and interests form an integral part of the checks and balances needed to prevent a tyranny of the majority. Unfortunately, the political dynamics of the country make the forging of partnerships with other language and cultural communities really difficult, because there are not enough strong, organised cultural communities that have escaped the suction power of the central government’s political co- optation.

Therefore, the strategy of the Solidarity Movement, the largest institution in the Afrikaans cultural society (350 000 families), is to provide essential services through a family of strong self-help community organisations; Solidarity’s strategy also includes engagement with authorities; using and protecting our constitutional spaces and opportunities; and pursuing communal interests with the majority.

Representivity

In a multicultural country, few institutions will automatically reflect the composition of the population. The democratic alternative should be that all institutions together should reflect the demographics on account of the constitutional provision for freedom of association. Cultural communities, wishing to exercise their democratic right at, for instance, single- medium universities, should not merely be tolerated due to democracy; they should be actively supported due to multiculturalism.

Forced transformation of all institutions to reflect the population composition strengthens cultural dominance by the majority and entrenches monoculturalism even further. The compulsion to make all institutions representative of the total population is undemocratic and unconstitutional, and it will culminate in a monocultural system where every aspect of the lives of minorities will be controlled by the majority. However, as proclaimed in the UN’s Human Development Report of 2004, “If the history of the 20th Century showed anything, it is that the attempt either to exterminate cultural groups or to wish them away, elicits a stubborn resilience”.

Unity in diversity

It is understandable that there might be concern that any recognition of cultural diversity could hamper national unity. That is why unifying and common interests should also be emphasised instead of artificially imposing common beliefs by means of clumsy nation- building strategies. These common interests that promote national unity are issues such as the necessity to have a functioning and successful country; peaceful coexistence and healthy race relations; a vibrant and growing economy that can solve the problem of poverty in the country; a healthy environment; unifying social values; upholding the rule of law; and a future in which everyone can live a free, secure and prosperous life.

A political compromise

Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor said that intergroup trust in multi-ethnic societies cannot be taken for granted but should always be regarded as work in progress. There was a time when high levels of this essential trust did actually exist, and then it was collated and institutionalised in the Constitution. However, Taylor rightly points out that this cannot be a once-off process, and that this trust should be renewed on a regular basis. The concern is that in South Africa, trust has reached such a low point that we can call it a trust crisis.

Therefore, the time has come to renew the intergroup trust with a national dialogue that could lead to what Prof. Pierre du Toit called a “follow-up agreement”; this amounts to preventative maintenance of the constitutional dispensation. However, the current political realities complicate the chances of reaching such an agreement, and in future it will become increasingly difficult to realise our constitutional language and cultural rights. It nonetheless remains essential to reduce the growing gap between the constitutional multicultural spaces and the shrinking political space to accommodate them.

The future of multiculturalism in South Africa

Over the years, there were many discussions between the Afrikaner cultural community and the government regarding the relentless movement towards multiculturalism despite the lip- service paid to the multicultural spaces in the Constitution. Unfortunately, these discussions have not yet resulted in a fixed outcome despite all the burning issues pointed out.

Despite this, the Constitution and the United Nations’ Human Development Report provide promising starting points on which to build. There are at least three possibilities that can be discussed with the government, namely a cultural follow-up agreement, a cultural contract between the government and minority groups, and a charter of cultural rights and freedoms that can be included in the Constitution as a supplement to the Human Rights Charter.

Of course, the ANC will not easily be persuaded to respect the existing constitutional spaces for multiculturalism and to implement the recommendations of the relevant UN report. However, history has shown time and time again that in our current day and age, no government can indefinitely ignore credible calls for (cultural) freedom. Lobbying among all communities in South Africa and abroad will be required in order to realise this dream.

The growing crisis in the country can force the ANC to face reality and to realise that they do not have the ability to overcome the country’s problems on their own. However, unless this happens, the chances of a comprehensive political realignment or a follow-up agreement is small, and other solutions for the current cul-de-sac in which the country finds itself will have to be sought.

In practice, numerous discussions and meaningful negotiations actually do take place at other levels, such as at local government level with municipalities about service delivery, where the relevant local authority has no alternative but to talk to AfriForum about resolving local crises. This also applies to cases where the Solidarity trade union participates in discussions with the authorities on issues of common interest, such as crises in the economy.

Therefore, the Solidarity Movement will continue its strategy to declare its willingness to hold meaningful discussions with government; to create realities that must be recognised; and to promote the conditions for successful agreements, such as improving the balance of power, forging partnerships, and, through numerous discussions and negotiations, to actually negotiate a comprehensive series of “follow-up agreements” as one central agreement.

Although, due to circumstances a negotiating strategy for a follow-up agreement or agreements cannot be the main strategy for multiculturism, it remains an important part of a future strategy to make Afrikaners permanently free, safe and prosperous. This is the condition in terms of which Afrikaners will make a sustainable contribution to the wellbeing of the country and all its people.

Flip Buys

Chairperson: Solidarity Movement

Footnotes:

i Heywood, A. 2007. Political Ideologies. 4th Edition. Palgrave Macmillan. New York. p. 330.

ii Heywood, p 312.

iii Sisk, T, 1996. Power Sharing and International Mediation in Ethnic Conflicts, United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC.

iv Sachs, A In Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie 2006 (1) SA 524 (CC)

v Taylor, C. 1994. Multiculturalism and “The Politics of Recognition”. Princeton University Press.

vi United Nations Human Development Report 2004. Cultural liberty in today’s diverse world.

1 UN Plaza, New York, New York, 10017, USA

vii Geldenhuys, D. 2011. ’n Strategie vir kulturele vryheid in Suid-Afrika. ABN lecture given on 3 February.

viii Kissinger, H. 2004. Bush and a scared new world. Tribune Media services.

ix Horowitz, D. 2001. Ethnic groups in conflict. University of California Press. Berkeley. x Du Toit, P. 2009. Suid-Afrika en die saak vir ’n opvolgskikking. Paper deliverd at a Solidarity conference.

xi Malan K. Observations on representivity, democracy and homogenization TSAR 2010 (3) 427-449