Wednesday, March 21, 2012

“Just a year before the declaration of the Republic, an event occurred at Sharpeville in the Transvaal, in 1960, which would resonate around the world, and forever-after be used as anti-Afrikaner propaganda. A mob of about 6,000 blacks, protesting against a law which compelled them to carry identification-passes allowing them to work in “white” areas, surrounded a police station. The ostensibly “peaceful” demonstration turned ugly when a woman inserted a gasoline-soaked rag into the fuel-receptacle of a police vehicle and then lit it. The resultant explosion panicked the small contingent of besieged policemen (already on edge due to the fact that 9 young policemen had recently been hacked and burned to death by a mob near Durban). A known criminal in the crowd then fired a shot at a policeman he recognized, standing in the doorway. The commander at Sharpeville ordered his policemen to be ready to shoot, but only if the masses broke down the fence; their last line of defense around the police station. When the mob stormed through the fence, firing broke out, and 69 of the rioters were killed. The senior police commander Lt. Colonel Pienaar later told a commission of inquiry into the “Sharpeville Massacre” that: “The Native mentality does not allow for a peaceful demonstration. For them to gather [together], means violence.” Although the white Afrikaner, by virtue of their 3 centuries of contact with black Africans, could claim to “know” them better than any other white nation did, a liberal media’s spin on these events, led to a world-wide perception that the Afrikaners were violent “white supremacists” and thus international sanctions against them were necessary.” – Bulala, by Cuan Eglin

Events leading up to the attack on Sharpeville Police Station in March, 1960

Saturday, April 18, 2009 at 5:09am

Afrikaner Broadcasting Corporation

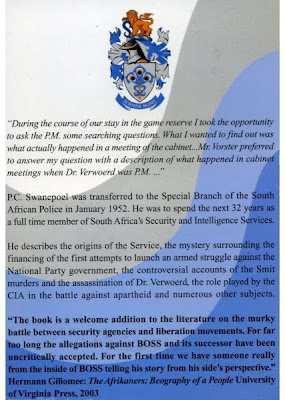

The literary work by P.C. Swanepoel titled Really Inside BOSS, was used as a source of reference for the following article. During the terrorist attack on the Sharpeville Police Station, Mr. Swanepoel was an employee of the Bureau of State Security (BOSS) and describes in detail the causes which led up to the events at Sharpeville on 21 March, 1960.

The South African Government and Police were vilified following the Sharpeville attack. The most common criticism accused a lack of compromise and negotiation by the State when dealing with the terrorist element in question. The police were facing extremist terrorist leaders determined to undermine the State and the terrorists did not hesitate to sacrifice innocent lives in pursuit of their aims. The police were not trained as negotiators. Ordinary policemen were fulfilling their designated duty to uphold law & order helping to maintain the peace. The situation which transpired at Sharpeville spiralled out of control, the police reacted accordingly defending life and property.

The ANC embarked on a ‘potato boycott’ in May, 1959, after sensational reports in a journal aimed at black readers alleged a potato farmer in the Bethal district had mistreated his workers. A ‘stay-at-home’ was organised as a reinforcement of the boycott. Simultaneously a crowd of several thousand rioters had gathered at the Cator-Manor slum on the outskirts of Durban. The rioters initially attacked the municipal beer hall.

The police were called to the scene and rumours spread of the police being vastly outnumbered. Strong suspicion was present of ANC cadres instigating the beer hall attack. The police would baton charge the attackers, who would retreat and subsequently regroup a short distance away, repeating the attack on the beer hall. The police would withdraw, whereupon the mob would attack the police with stones. The situation was seemingly close to resolution.

In a sudden turn of events a school bus filled with small black children drove slowly past the rioters. The black mob assaulted the driver of the school bus, smashing the bus windows with the petrified children inside; they set the bus on fire. Two of the rioters stationed themselves at the door of the bus preventing any children from leaving. The children were forced to escape through jagged glass windows, falling to the ground bloodied and bruised, whereupon the mob would beat the small children with sticks. Mr. P.C. Swanepoel was an eyewitness to these events.

The Government had implemented the liquor act, forbidding blacks from buying European liquor. The regulation was not distinctly South African. The precursor to the United Nations, The League of Nations mandating the territory of South West Africa to South Africa, specifically forbade South Africa from allowing access to European liquor by the indigenous black population. Reluctantly the police were obligated to enforce this act, increasingly turning the natives against them. The raids in Cato Manor were conducted by black and white policemen and were greatly resented by the black inhabitants. All liquor discovered was destroyed on site. A few weeks before Sharpeville, one of the raids went badly wrong. A raiding party of black and white policemen were surrounded and attacked by a crowd of several hundred blacks. The white policemen were armed with revolvers, the black police carried batons. Despite screams from their black police comrades soliciting them to use their revolvers, the white policemen attempted to reason with the mob, resulting in the entire group being murdered.

Previous to this incident, in the 1950’s a similar situation transpired. Sergeant Shorty de Lange, a fluent Zulu speaker, led a party of policemen to a dagga (cannabis) plantation in Natal. The party was surrounded by approximately a hundred Zulus. The black policemen pleaded with him to command the opening of fire, refusing and opting to negotiate instead. Resulting in all the white policemen and most of the black policemen being killed.

Against this background occurred the events at Sharpeville. The global outrage was the fact that white policemen had fired upon black rioters. Quoting the CIA financed New African (January, 1962), “Sharpeville would have had less impact had a white reporter not been there”. A few years after the Sharpeville attack, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis were slaughtered by their black countrymen in Central Africa, no one in Europe had knowledge of this genuine massacre.

At Sharpeville, the police were aware of the riotous mob surrounding them. With hundreds of sticks and traditional weapons threatening the lives of the few policemen. The defence of the Police Station was of critical importance, this had been emphasised during their police training, since it was a bastion of the State and a symbol of authority, to be defended at any cost. In defence of a Police Station the use of firearms was rightly justified.

Tom Lodge offers an account of what occurred in Sharpeville.

The Pan African Congress began their preparations at Sharpeville in March, 1960. The instigators would confront people at bus stops compelling them to burn their identity documents (Passbooks a form of Passport used by migrant labourers on work contracts in the Republic of South Africa). On the night of the 20th of March, 1960, the terrorists targeted the residences of the local bus drivers, kidnapping them. The following morning the township population was impeded from getting to their place of work. The terrorist instigators pressured the general population to head towards the police station. Two Impala Airforce Jets patrolled the skies above the crowd of over 5,000 armed people surrounding the police station, for three hours the instigators challenged the police to arrest the intimidating multitude. The police refused and called for reinforcements which arrived in Saracen armoured vehicles after midday. The perimeter fence around the police station was breached by the threatening crowd; they proceeded to attack the outnumbered police officers. For thirty seconds the police fired in self-defence, dispersing the crowd and leaving 67 fatalities and 167 injured.

The attack upon the policemen of Sharpeville was a premeditated attack against the State, the guarantors of the authority of the State, the police were left with no option being confronted with an armed and violent crowd vastly outnumbering the few policemen. The terrorist leaders & instigators achieved their initial objective; by sacrificing the lives of their supporters they could draw the hysteria of the global media.

» » » » [Afrikaner Broadcasting Corporation]

Really inside BOSS: a tale of South Africa’s late intelligence service (And something about the CIA)

by P.C. “Piet” Swanepoel

Paragraphs excerpted from Pages 10 – 14:

|

» » » » [Really Inside Boss]