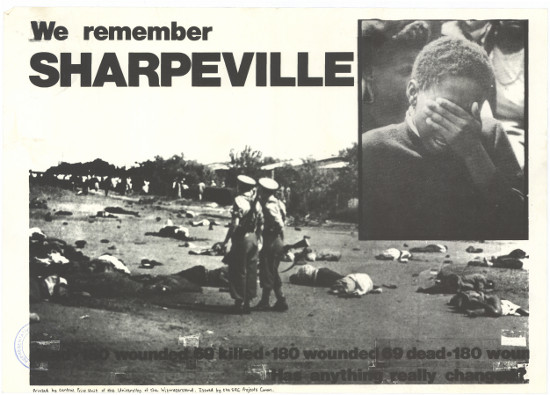

On 21 March 1960 at least 180 black Africans were injured (there are claims of as many as 300) and 69 killed when South African police opened fire on approximately 300 demonstrators, who were protesting against the pass laws, at the township of Sharpeville, near Vereeniging in the Transvaal. In similar demonstrations at the police station in Vanderbijlpark, another person was shot. Later that day at Langa, a township outside Cape Town, police baton charged and fired tear gas at the gathered protesters, shooting three and injuring several others. The Sharpeville Massacre, as the event has become known, signalled the start of armed resistance in South Africa, and prompted worldwide condemnation of South Africa’s Apartheid policies.

A build-up to the massacre

On 13 May 1902 the treaty which ended the Anglo-Boer War was signed at Vereeniging; it signified a new era of cooperation between English and Afrikaner living in Southern Africa. By 1910, the two Afrikaner states of Orange River Colony (Oranje Vrij Staat) and Transvaal (Zuid Afrikaansche Republick) were joined with Cape Colony and Natal as the Union of South Africa.

After the Second World War the Herstigte (‘Reformed’ or ‘Pure’) National Party (HNP) came into power (by a slender majority, created through a coalition with the otherwise insignificant Afrikaner Party) in 1948. Its members had been disaffected from the previous government, the United Party, in 1933, and had smarted at the government’s accord with Britain during the war. Within a year the Mixed Marriages Act was instituted the first of many segregationist laws devised to separate privileged white South Africans from the black African masses. By 1958, with the election ofHendrik Verwoerd, (white) South Africa was completely entrenched in the philosophy of Apartheid.

There was opposition to the government’s policies. The African National Congress (ANC) was working within the law against all forms of racial discrimination in South Africa. In 1956 had committed itself to a South Africa which “belongs to all.” A peaceful demonstration in June that same year, at which the ANC (and other anti-Apartheid groups) approved the Freedom Charter, led to the arrest of 156 anti-Apartheid leaders and the ‘Treason Trial’ which lasted until 1961.

By the late 1950s some of ANCs members had become disillusioned with the ‘peaceful’ response. Known as ‘Africanists’ this select group was opposed to a multi-racial future for South Africa. The Africanists followed a philosophy that a racially assertive sense of nationalism was needed to mobilise the masses, and they advocated a strategy of mass action (boycotts, strikes,civil disobedience and non-cooperation). The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) was formed in April 1959, with Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe as president.

The PAC and ANC did not agree on policy, and it seemed unlikely in 1959 that they would co-operate in any manner. The ANC planned a campaign of demonstration against the pass laws to start at the beginning of April 1960. The PAC rushed ahead and announced a similar demonstration, to start ten days earlier, effectively hijacking the ANC campaign.

The PAC called for “African males in every city and village… to leave their passes at home, join demonstrations and, if arrested, [to] offer no bail, no defence, [and] no fine.”1

On 16 March 1960 Sobukwe wrote to the commissioner of police, Major General Rademeyer, stating that the PAC would beholding a five-day, non-violent, disciplined, and sustained protest campaign against pass laws, starting on 21 March. At a press conference on 18 March he further stated: “I have appealed to the African people to make sure that this campaign is conducted in a spirit of absolute non-violence, and I am quite certain they will heed my call. If the other side so desires, we will provide them with an opportunity to demonstrate to the world how brutal they can be.” The PAC leadership was hopeful of some kind of physical response.

References:

1. Africa since 1935 Vol VIII of the UNESCO General History of Africa, editor Ali Mazrui, published by James Currey, 1999, p259-60.

A few days before the massacre a pamphlet was circulated in the townships near Vereeniging (Sharpeville, Bophelong, Boipatong, and Evaton) calling for people to stay away from work on the Monday. The PAC, however, was not prepared to leave the demonstration to public choice. Testimony was given at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings that the telephone lines between Sharpeville and Vereeniging were cut on the Sunday evening, and that (some) bus drivers were detained until the Monday morning to stop people travelling out of Sharpeville to work. 2

“Evidence before the Commission points to a degree of coercion of non-politicised Sharpville residents who were pressurised into participating in the anti-pass protest.“3

By 10 in the morning almost 5,000 protesters had congregated in the centre of Sharpeville, from where they walked to the police compound. Similar groups (about 4,000 in total) walked from Bophelong and Boipatong to the police station at Vanderbijlpark, whilst a larger gathering of almost 20,000 people formed at the police station in Evaton.

The crowd at Evaton was dispersed by low-flying Sabre jets, and that at Vanderbijlpark was dispersed by a baton charge and tear gas. One person was killed at Vanderbijlpark when the police opened fire in response (the police claimed) to stone throwing by the crowd. At Sharpville, with a number of PAC officials in the crowd, the low-flying jets had no effect. The crowd remained around the police compound, waiting for a PAC statement to be read out.

In the official TRC version of events the police remained passive until one-fifteen. Despite claims in the press in 1960 (and still in many reports) that squads of police went out into the crowd to arrest PAC officials, no action was actually taken by the police against the PAC at that time. “The police refused to arrest PAC members who presented themselves for arrest.”4 Police accusations that the PAC leadership refused to instruct the crowd to disperse, however, were deemed false: various officials did in fact ask them to move away from the compound’s fence. Only 300 or so protesters were still in the vicinity when the shooting started (this means, however, that the police managed to shoot almost all those near to the compound). By mid-day the small contingent of police normally present at the station (12 in all) had been boosted significantly: nearly 300 armed police and five Saracens (armoured vehicles) were present.

No one knows why the first shot was fired. The police claim it was in response to stone throwing by the crowd, and although this is mostly dismissed, such debris is visible amongst the fallen bodies and discarded footwear in photographs of the aftermath. The first shots being fired in response by inexperienced and nervous officers. (Rarely mentioned in contemporary reports is that the police were nervous because, only a few weeks before, nine policemen had been killed by a mob at Cato Manor, a township outside Durban.) Eyewitnesses from the crowd claim that an order was given to fire, or that the banging of a Saracen door was mistaken for gunfire from the crowd. No firm evidence for any weapons amongst the crowd (guns or traditional spears and knobkerries) has ever been given. The TRC concluded that there was a “degree of deliberation in the decision to open fire at Sharpville” which indicated “that the shooting was more than the result of inexperienced and frightened police officers losing their nerve.“5

Somewhere between 50 and 75 of the police opened fire. The crowd initially confused, and perhaps thinking the police were using blanks, stood still. It was not until the bodies started to fall that they ran. The police continued to shoot the protesters even as they fled from the site. Of the 180 injured, only 30 had been shot from the front. The injured included 31 women and 19 children, while among the 69 killed, eight were women and ten children.

It took a while for emergency services to arrive (the telephone lines had been cut) and the police were slow to provide help. Following the massacre, the police made 77 arrests, including several people still receiving treatment in hospital (they were placed under guard until they were fit enough to be detained). Of those arrested, 55 were later released.

Read the TRC conclusion about Sharpeville.

References:

2. Truth and Reconciliation Commission report Vol 3 Chapter 6 para 29.

3. ibid para 28.

4. ibid para 32.

5. ibid para 34.

In September that year 224 civil claims for damages were served against the Minister of Justice. The government’s response was the Indemnity Act (1961): legislation that indemnified the government and its officials retrospectively against such claims. (Shortly afterwards, in response to public pressure, the government set up a committee to examine the claims and to recommendex gratia payments; but few were actually paid out.)

What caused worldwide condemnation was not so much the deaths (such killings are more common that we would like to think: Frank Welsh in his History of South Africa6 compares it to ‘Bloody Sunday’, Londonderry January 1972, and the shooting of Kent State University students, Ohio 1970) but the callous way in which the Apartheid government put the blame squarely on the dead and injured.

It had only been six weeks since the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, had given his “winds of change” speech in Cape Town. Britain, who had consistently vetoed United Nation sanctions against South Africa could no longer condone South Africa’s actions.

Rather than instigate a change in policy, Apartheid was more rigidly applied. A state of emergency was declared on 30 March (it lasted until 31 August 1960) and 18,000 black strikers were detained. On 8 April the Unlawful Organisations Act (1960) declared both the ANC and PAC illegal. The following day a disgruntled farmer, David Pratt, attempted to assassinate the South African Premier Dr Hendrik Verwoerd. Rather than have a white man be held culpable for the assassination attempt, Pratt was found mentally ill.

A referendum of the white electorate in South Africa in October 1960 voted for a republic government (52% to 47%, reflecting the division between Afrikaans and English voters). Verwoerd consequently withdrew South Africa from the Commonwealth of Nations in March 1961 and South Africa became a republic on 31 May 1961.

In the crisis that followed the ANC and PAC were banned, and the ‘armed struggle’ was launched. Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and several others in the ANC leadership formed its military wing,Umkonto we Sizwe or MK (the Spear of the Nation), on a farm at Rivonia. Mandela acted as chief-of-staff, launching the MK’s sabotage campaign in December 1961. The Rivonia farm was raided in 1963 and the consequent arrests resulted in the infamous ‘Rivonia’ Trial which lead to the imprisonment for life of several ANC leaders (on Robben Island). The PAC also set up its armed wing, POQO, which means independent ‘ or ‘stand alone’ (the PAC was completely opposed to multi-racial solutions in Africa) in 1961.

Following the ban the ANC and PAC were forced to go underground and operate from outside South Africa. Internal opposition was left to people like Steve Biko and the members of the Black Consciousness Movement.

In 1966, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 21 March, the anniversary of the Sharpeville massacre, as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

In 1996, on the 26th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre, Nelson Mandela chose Sharpeville as the site to announce the signing of the new democratic constitution. The day is now commemorated as South Africa’s Human Rights Day.

References:

1. Africa since 1935 Vol VIII of the UNESCO General History of Africa, editor Ali Mazrui, published by James Currey, 1999, p259-60.

2. Truth and Reconciliation Commission report Vol 3 Chapter 6 para 29.

3. ibid para 28.

4. ibid para 32.

5. ibid para 34.

6. A History of South Africa by Frank Welsh, published by Harper Collins, 1998, ISBN 0-00-255561-1.